Post-Polio Health Care

Considerations

for

Families R Friends

Joan L. Headley, MS, and Frederick M. Maynard, MD

WITH

Stephanie T. Machell, PsyD, and Holly H. Wise, PT, PhD

P

UBLISHED BY

Post-Polio Health International

post-polio.org

©

Copyright 2011 Post-Polio Health International

4207 Lindell Blvd., #110, St. Louis, Missouri 63108-2930

314-534-0475, 314-534-5070 fax, [email protected]

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations

for

Families R Friends

Joan L. Headley, MS

Post-Polio Health International, St. Louis, Missouri

Frederick M. Maynard, MD

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Marquette, Michigan

WITH

Stephanie T. Machell, PsyD

International Rehabilitation Center for Polio, Framingham, Massachusetts

Holly H. Wise, PT, PhD, Associate Professor, Division of Physical Therapy,

College of Health Professions, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina

P

UBLISHED BY

Post-Polio Health International

post-polio.org

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families & Friends

ADVISORS

David C. Bailey, son of Phyllis Bailey

Barbara Duryea, MSN, RN, CPHQ

John P. Murtha Neuroscience & Pain Institute, Johnstown, Pennsylvania

Sandra Loyer, LMSW

University of Michigan (retired), Ann Arbor, Michigan

SUPPORT

The Phyllis and Max Reynolds Foundation Inc.

Marquette, Michigan

WITH ADDITIONAL ASSISTANCE FROM

The Chervenak-Nunnallé Foundation

New York, New York

Dedicated to the family of Kathleen Navarre

Introduction

“My father is in the hospital slowly recovering from prostate

cancer surgery. The physical therapist tells us he ‘should be

walking’ by now. As a kid growing up, I knew his limp was

from polio but he never talked about it. I need to learn about

polio. I am embarrassed to say, but I don’t know anything

about it. Is his polio causing problems after all these years?”

“My sister choked on some food, passed out and is in the

hospital with a tube down her throat (intubated) so she can

breathe. What information should I give the physicians so we

are sure they understand how having had polio could affect

her recovery.”

“My mother is in the ICU after a heart attack. When I first

saw her, I didn’t recognize her. She always took control of her

own health issues (and didn’t trust physicians much). I recall

her saying that most physicians don’t know polio. How can

I be sure she is getting the best treatment?”

I

n the ‘80s and ‘90s, polio survivors themselves searched for answers

to their new health problems, and Post-Polio Health International

(PHI) responded by creating informational publications specifically

for them. The change was gradual

but

by the mid-2000s, more calls came

from family members and friends than

from polio survivors themselves.

The callers expressed fear, ignorance, confusion and guilt. They were

afraid of what might happen to their loved one, ignorant of the basic

facts about polio, confused about the late effects of polio and guilt-ridden

because of what they did not know.

Recognizing the problem, PHI received funding from The Phyllis and

Max Reynolds Foundation Inc. (Marquette, Michigan), with additional

assistance from The Chervenak-Nunnallé Foundation (New York, New

York), to develop answers to assure aging polio survivors receive appro-

priate medical treatment and care.

A panel of experts (see facing page) with experience in treating and educat-

ing the survivors of polio compiled facts and wisdom targeting family

members and friends caring for relatives who had polio. Polio survivors

and families suggested items to be included in the packet of information

and reviewed it.

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends 5

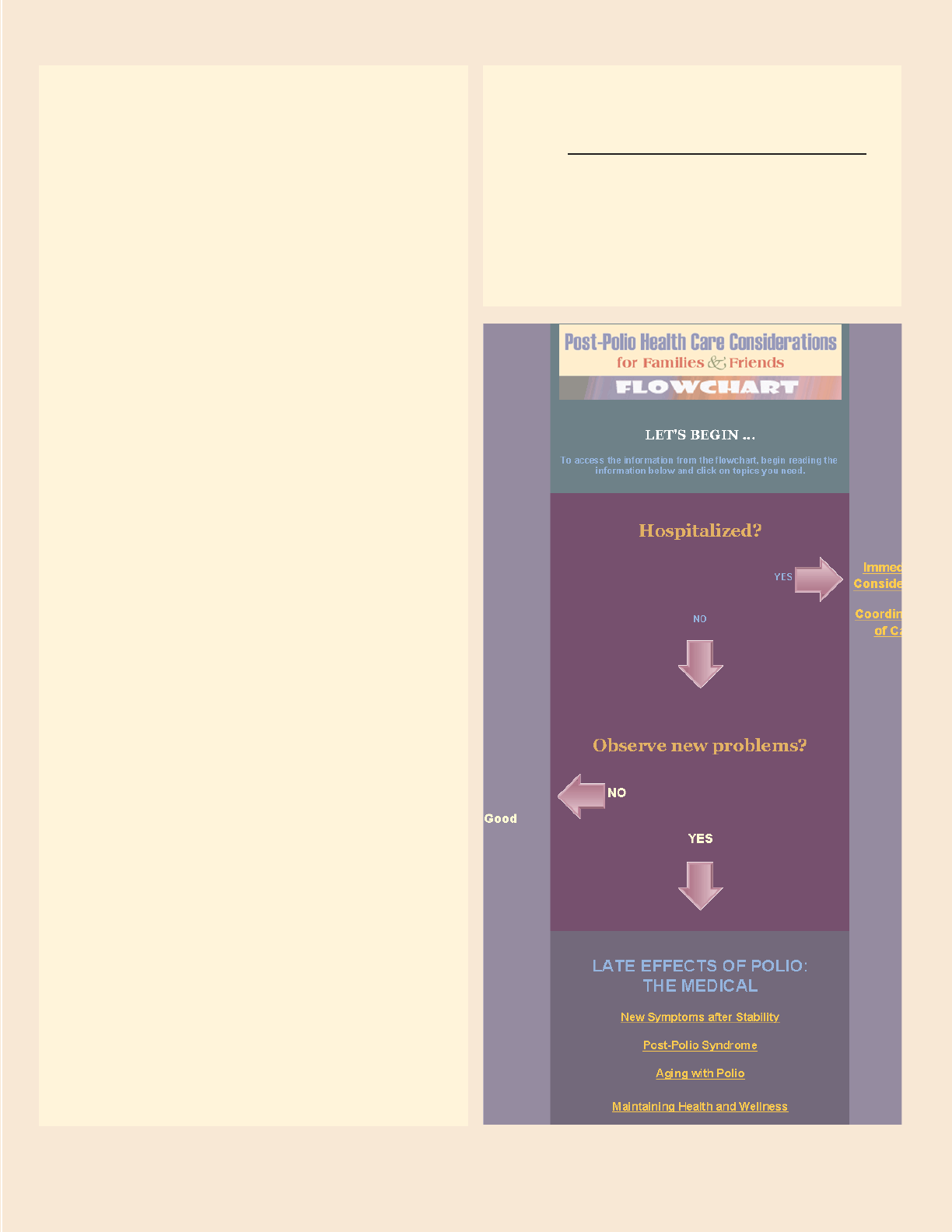

Getting Started:

Two Options

1

A flowchart organizes numerous topics

to assist you. Click on “Let’s Begin”

to view the flowchart. To move through

it, answer “yes” or “no” and click on the

phrase that describes your immediate

need to find useful information.

2

This booklet presents the same infor-

mation in clearly marked sections

beginning with a detailed outline (see

facing page). Use the outline and click

on the topic of your choice.

In this document, polio survivor is

indicated by terms such as parent, family

member, loved one and often as friend.

These terms are interchangeable.

6 Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends

OUTLINE

I. Considerations for Hospitalized

Polio Survivors

II. Late Effects of Polio: The Medical

A. Polio: The Disease

B. New Symptoms after Stability

C. Post-Polio Syndrome

D. Aging with Polio

E. Maintaining Health and Wellness

III. Late Effects of Polio: The Psychosocial

A. Polio: The Experience

B. Models of Disability/Identity Issues

C. Coping with Stress and Physical Changes

D. Relationships: Families and Friends

IV. Management/Treatment Ideas

A. Pain

B. Weakness

C. Fatigue

D. Breathing and Swallowing Problems

E. Depression and Anxiety

F. Trauma

V. Evaluation of Options within the Family

VI.Professional Assistance

A. Family Physician

B. Health Care Specialists

C. Coordination of Care

VII. Plan for the Future –

Don’t Reinvent the Wheel!

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends 7

FLOWCHART

Visit www.post-polio.org/edu/healthcare

to view the information about your loved

one’s post-polio care considerations by using

the flowchart and answering the questions

“yes” or “no” then reading the sections that

apply to your polio survivor’s needs.

U

nexpected stays in the hospital, even though necessary, are frustrating, because

hospitals are overwhelming places. The job of the medical staff is to treat

patients and to explain procedures. Ask questions until you fully understand

what is involved in the procedures and treatments.

Expect to interact with health professionals who have never treated a polio survivor,

but don’t be alarmed. The immediate issues are practical in nature and not dependent

on an extensive knowledge of the disease of polio. Professionals generally understand

neuromuscular diseases, such as muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, ALS and

polio. However, some mistakenly think that polio paralysis means the lack of feeling.

Polio people can “feel” when their weakened or atrophied muscles are touched, and

in fact, these body parts can be more sensitive.

Remember it is always appropriate to ask for a second (or third) opinion if you are

uncomfortable with the treatment plan.

Here are a few things to consider if your loved one is in the hospital.

Get to know the key personnel on the hospital staff. Remind them that a person

who has lived with a disability for a long time is the most qualified to manage

his/her functioning and general day-to-day care.

Inform staff of the person’s limitations due to prior polio along with instructions

as to how he/she carries out necessary tasks, e.g., can walk only with a brace,

cannot reach out to receive medications or water, cannot lie on right side, uses

nighttime ventilation, etc. Relaying this information is vital if your parent or

friend can’t speak for him or herself, and it signals to the staff that you want to

be actively included in their care.

After compiling this information in written form, ask the staff to be flexible and

creative in adapting their medical procedures so your family member receives

the best care. Request that the staff place the information in the chart for all

personnel to see.

Polio survivors have weakness from prior polio and from years of overuse of muscles

and joints. This weakness increases as they age. Less common is weakness from disuse

or inactivity, but it can occur during hospital stays. Sometimes, it is more expedient

for staff to let polio people stay in bed because of the additional assistance they need.

Activity is beneficial and family members can offer to assist their loved ones, so the

survivors have an opportunity to be active to the best of their ability.

Polio survivors who use home mechanical ventilation at night or 24 hours a day,

either with a tracheostomy (surgically-made hole in the throat) or with a nasal or face

mask, may need the most attention when hospitalized. Many emergency care profes-

sionals are not familiar with portable breathing devices and the newer nasal and face

masks (noninvasive ventilation) used in the home. The tendency is to replace the

I. Considerations for Hospitalized Polio Survivors

8 Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends 9

equipment with the more familiar hospital equipment and methods, such as intubation

(a breathing tube placed into the windpipe through the mouth) and a tracheostomy.

While these hospital-based devices and methods may be necessary at times, polio

survivors may avoid them by using their own equipment in the hospital. It may be

necessary to adjust the settings of the breathing device, the specific type of nasal

and/or face mask in use, and the amount of time on machine, etc., during a hospital

stay. The breathing device may need to be “checked out” by the hospital’s engineering

department before it can be used in the hospital.

In an emergency, a tracheotomy may be necessary to save one’s life, but physicians

can attempt to change back to the original equipment used for breathing once the

crisis is over.

Be Prepared

The best scenario is to be prepared for hospitalization. Discuss unique health concerns

with the primary care physician, pulmonologist or other specialists to obtain their

agreement to act as an intermediary with other hospital staff during emergencies. The

goal of the emergency room physician is to save lives, so expect them to address the

most critical problems first.

Discuss with polio survivors who they want to make decisions in case they cannot.

The selected individual has durable power of attorney for health care (medical power

of attorney) and can legally make medical decisions for your loved one.

Ideally, your parent or friend will have completed the legal forms stating their wishes

in case they can’t speak for themselves. Families who have discussed the nitty-gritty of

the various possible choices at life’s end in advance have a distinct advantage during

a crisis. Many polio survivors have spent a lot of time and energy “fighting against

death” and it may be difficult to engage them in an honest, meaningful discussion

about this topic.

It may be beneficial to remind them of the advances in technology and that you would

like clear instructions to respect their wishes. Another compelling reason for them to

plan is the number of physicians and specialists you as their child or friend may en-

c

ounter in the hospital, all who will have differing ideas about prognosis and treatment.

Pre- and Post-Surgery

Prior to surgery, evaluate the home, specifically the bathroom and the bedroom, to

accommodate for post-surgery limitation. It can be beneficial to meet with the post-

surgery physical therapist before surgery, so they can assess the polio survivor’s muscle

strength to establish a baseline that can be used for planning an exercise program for

both in the hospital and when back home.

If your loved one’s post-polio issues are complicated, consider having surgery done

in a large teaching hospital, because staff members conduct pre-surgery “clinics” to

exchange information about each patient. In other situations, schedule a face-to-face

discussion with the anesthesiologist several days prior to any planned surgery and tell

them your loved one had polio and your concerns, including a request for closer post-

op monitoring than typical. The anesthesiologist assigned to a patient can change, so

discuss the relevant information and request that they pass it along to the team.

To minimize complications when emergencies occur outside of a local area, encourage

polio survivors to carry a

n information sheet containing brief instructions about their

medical condition and contact phone numbers with them at all times. You and other

family members should have a copy, also.

Intensive Care

If your loved one is in intensive care, attempt to get their primary care physician or

the health professional who best knows their post-polio health history

involved with

the ICU professionals to help explain or reinforce your unique concerns

. Remember

having had polio can compound the effects of other illnesses or surgery. Having

major surgery is difficult for healthy people and it can be more difficult for those who

had polio.

Recovery time may be longer. Don’t get discouraged. Watch for signs of improvement

.

Encourage appropriate exercise to counter disuse weakness acquired while your

family

member is inactive, so he/she can return to their “normal” day-to-day activities. Many

polio survivors reject any exercise out of fear of overuse weakness, but explain

ing

the difference between overuse weakness and disuse weakness can alleviate that fear.

Family members can assist with personalized exercise once home therapy ends.

Reminder: Ask questions. Be an advocate. Try to think one step ahead so you

are prepared.

If you have concerns about treatment specifically related to breathing issues,

ask the pulmonologist to speak with a pulmonologist who is experienced in treating

polio survivors. (See Resour

ce Directory for Ventilator-Assisted Living.)

10 Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends

Summary of Anesthesia Issues for the Post-Polio Patient (post-polio.org, 2009)

Anesthesia Update: Separating Fact from Fear

(PHI’s 10th International Conference, 2009)

To Have Surgery or Not to Have Surgery – That Is the Question!

(Post-Polio Health, 2008)

Surgery: Another Point of View (Post-Polio Health, 2009)

Introduction to Take Charge, Not Chances (Ventilator-Assisted Living, 2007)

Home Ventilator User’s Emergency Preparation Checklist

Caregiver

’s Emergency Preparation Checklist

P

atient’s Vital Information for Medical Staff (pdf) (Word option)

T

reating Neuromuscular Patients Who Use Home Ventilation: Critical Issues

Care of a T

racheostomy (Ventilator-Assisted Living, 2005)

more ...

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends 11

A. Polio: The Disease

Poliomyelitis (polio) is a viral illness that begins suddenly with flu-like symptoms of

fever, headache, vomiting and/or diarrhea, muscle aching and “feeling poorly.” The

virus enters the body through the stomach and intestines. In some people (about 10%

of cases), the virus can enter into the central nervous system (the brain and spinal

cord) and produce damage to motor nerve cells, whose function is to instruct muscles

to move. About 1-2% of people who get the infection develop some lasting weakness

from dying of motor nerve cells. The amount of lasting weakness depends on how

many motor nerve cells die and can vary from a small amount (only a few muscles are

a little weak) to a large amount (most muscles are very weak or completely paralyzed).

After the initial infection symptoms improve, most people begin a stage of recovery

and healing. In those with only a relatively small loss of nerve cells going to a muscle

(30-50%), weakness can improve slowly and reach the point where strength is again

enough to allow survivors to use their arms and legs for usual daily activities. In sur-

vivors left with a lot of weakness in many muscles, recovery of muscle strength and

ability to function may be very slow and can involve many years of rehabilitation

treatments, including physical therapy, use of assistive aids, such as braces, crutches,

wheelchairs, ventilators and surgeries.

Most polio survivors worked very hard to make as good a recovery as possible and

were helped and encouraged by their parents, friends and medical professionals.

Improvements usually continued for two or more years. Polio survivors, such as your

loved one, eventually reached a “period of stability” when muscle strength and func-

tional abilities did not improve. For those people who had polio as infants or young

children, rehabilitation efforts continued throughout their childhood and teenage

years, and they most likely gained their best possible functional abilities after 2-18

years of rehabilitation.

History of Polio (PHI’s Handbook on the Late Effects of Poliomyelitis for

Physicians and Survivors)

What is poliomyelitis? (Centers for Disease Control)

Poliomyelitis in “The Pink Book” (Centers for Disease Control)

more ...

II. Late Effects of Polio: The Medical

B. New Symptoms after Stability

Many people with a history of paralytic polio (polio infection resulting in lasting weak-

ness) begin having new symptoms (complaints and problems) related to muscle strength

and functional abilities after a stable period of 15 or more years. The most common

complaint is fatigue, described as either “no energy or being too tired” to do any phys-

ical activity (being fatigued), or tiring out very fast after doing even just a little physi-

cal activity (having rapid fatiguability), or both. Fatigue and rapid tiring out may be

limited to only certain muscles or may be exhaustion throughout the whole body.

The second most common symptom is new weakness of specific muscles. Your parent

or loved one may experience a decline in their “personal best” strength of muscles

that they always knew had been weakened by their old polio as well as muscles that

they thought had not been affected by the polio.

Some muscles may shrink and become smaller, a condition known as atrophy. Even

a small amount of loss of strength in some muscles may make a big difference in

a person’s ability to carry out daily activities even though the percentage of loss of

strength may not be large based on one’s personal best. What is important is how this

loss of strength affects the ability to function, e.g., get on and off the toilet, get out

of a chair, roll over in bed, put on shoes, tie them, etc.

The next most common symptom is pain. There are many reasons for polio survivors

to develop new aches and pains as they become older living with their polio weak-

nesses and polio-related abnormalities of arms, legs and spine. An unusual amount

of aching and soreness in the muscles after extensive use or doing specific activities is

a special problem among polio survivors. This aching suggests “overuse” of muscles

by asking them to do repeatedly more than they are capable of doing.

Other common symptoms are new breathing problems, choking and swallowing

problems, and the inability to tolerate cold places. Any or all of these common new

symptoms may reduce or limit polio survivors’ ability to carry out their usual daily

activities. For polio survivors who were more extensively affected, these “symptoms”

are not new, but increased, i.e., additional weakness, more difficulty in swallowing,

less and less ability to tolerate cold places.

C. Post-Polio Syndrome

Post-Polio Syndrome (PPS) is the name given to the group of common new symp-

toms (fatigue, new weakness and pain) experienced by polio survivors. The definitive

symptom is new weakness that is clearly not a result of another non-polio condition.

Most post-polio specialists think that PPS results from a slow worsening in the ability

of polio survivors’ nerves and muscles to work properly as they become older and/or

their health declines.

Medical research has not proved definitively what brings about PPS in some polio

survivors and not others. As a result, experts disagree on whether PPS is really a

“new disease” or a “condition” of declining strength and function that commonly

12 Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends 13

happens as polio survivors become older and develop other new health problems.

PPS is the diagnosis made when physicians look for and treat all of a survivor’s

symptoms (pain, weakness, fatigue, etc.) assuring that the non-polio related conditions

that may cause the same symptoms are cured or managed.

Because there is no cure or specific treatment for PPS, the answer to this disagreement

about “names” or “labels” is not the important issue. Treatment of PPS symptoms must

always be specific to an individual’s needs. The treatment will depend on how bad the spe-

cific symptoms are and how they affect a survivor’s most important functional abilities.

D. Aging with Polio

Due to recent advances in medical rehabilitation, emergency medicine and consumer

education, for the first time in history persons with disabilities, like their non-disabled

counterparts before them, are surviving long enough to experience both the rewards

and challenges of mid- to later-life.

Aging with polio’s after effects does not come without its problems. In exchange for

the personal benefits of increased longevity, many polio survivors experience new,

often unexpected health problems that result in changes in their ability to function

and threaten to diminish their independence and quality of life.

The development of PPS symptoms has received the most attention, but the health

risks are not limited to these problems. Living with the long-term effects of polio

also places survivors at potentially increased risk for age-related chronic diseases and

health conditions, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, bronchitis and

emphysema, osteoporosis and obesity, to name a few. While these conditions affect

the rest of the aging population, they may occur more frequently and at younger ages

for persons with disabilities, due to their “narrower” margin of health and the barri-

ers they face for maintaining good health.

Both PPS and other age-related chronic conditions can speed up the aging process

and result in loss of function at an earlier age than expected. Being aware of these

risks can be helpful because it encourages preventive steps and services. Acknowledg-

ing these potential problems allows survivors and you, their families, to prepare for

changes without the stress and fear that comes from sudden and completely un-

expected changes.

Remember Polio? Have you heard about the late effects of polio?

(post-polio.org)

What is Post-Polio Syndrome? (post-polio.org)

more ...

Living with Disability: Approaching Disability as a Life Course – The

Theory (PHI’s Sixth International Conference, 1994)

more ...

E. Maintaining Health and Wellness

Good health is being the best that one can be – physically, mentally, spiritually, emo-

tionally and socially. Polio survivors do not need to constantly struggle from one

health crisis to the next. While some health problems require professional assistance,

your parent or friend can manage other problems. In addition to seeing appropriate

health professionals to alleviate and manage the late effects of polio and other un-

related diseases, another aim of you and your polio survivor is to improve their day-

to-day overall sense of wellness and ability to participate in life.

Most of the ideas about staying well are the same for all people whether they have

a disability or are nondisabled, but a wellness program needs to be personalized.

One size does not fit all.

Not paying attention to safety issues can cause more suffering than many diseases.

Remind everyone in your family always to use a seat belt. If there is a gun in the home,

store it safely. With aging, problems with hearing and sight develop. Be sure the smoke

detector batteries are working and that your parent can hear them. Increase lighting,

especially on the stairs. Check your parent’s bathroom for grab bars and other safety

devices, such as a raised toilet seat. Check all the rooms for unnecessary objects that

may cause a fall, such as throw rugs and electric cords.

Encourage your parent or friend not to use tobacco or illegal drugs, to drink alcohol

in moderation, if at all, and to practice safe sex.

It is vital to eat a healthy diet and to exercise to maintain strength, burn calories,

decrease insulin resistance and prevent osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is a common

problem that may affect all people age 50 and older. Osteoporosis is an important

issue for polio survivors, because the polio-affected areas have less bone mass and

weaker bones because of the lack of “normal” weight bearing. Polio survivors will

fall more often than others. If they break their “good” hip or fracture an arm that

they depend on to assist in walking with canes, crutches, or to propel a wheelchair,

or for transferring, it will tremendously impact their lives.

Research has shown that calcium and vitamin D are important for strong bones and

most people don’t take in enough of either on a daily basis. The current recommen-

dation for adults over 50 is to take in 1,200 mg per day of calcium. Experts recom-

mend a daily intake of 600 IU (International Units) of vitamin D. Sources include

sunlight, supplements or vitamin D-rich foods such as egg yolks, saltwater fish, liver

and fortified milk. The Institute of Medicine recommends no more than 4,000 IU

per day. However, sometimes doctors prescribe higher doses for people who are

deficient in vitamin D.

To stay in the best health, polio survivors should see their primary care physician

regularly for preventive care. This visit should include measurement of height,

weight, cholesterol and blood pressure. More and more physician’s offices have exam-

ination tables that raise and lower to accommodate those in wheelchairs or with

mobility problems.

14 Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends 15

Preventive care includes age and sex specific considerations, such as testing for col-

orectal cancer for people age 50 or older. For men, it is advisable to have prostate

tests and possibly the blood test PSA (prostate specific antigen) done. Women need

to have breast exams, mammograms, pelvic exams, Pap smears and discussion of the

pros and cons of hormone replacement therapy.

Family physicians will monitor adult immunizations, such as diphtheria/tetanus once

every 10 years, and for persons with respiratory conditions, and/or age 65 or over, a

pneumonia vaccine. One pneumonia shot is good for at least 6 to 10 years. Ask about

the shingles (herpes zoster) vaccine if your parent had chicken pox. The varicella-

zoster virus (VZV) causes chicken pox and because it remains in the nervous system

for life, it can cause shingles. Polio survivors should get the annual flu vaccine, unless

there are reasons not to, such as an allergy to eggs. There has been no research to

suggest that polio people should not have a flu vaccine or a shingles vaccine based on

the fact they had polio.

Your parent’s primary care physician and/or appropriate health care professional will

be able to offer advice on all of these important issues.

Being well includes good mental health. Sometimes physical problems overshadow

mental health issues, such as the anxiety disorders, manic-depressive illness, eating dis-

orders and depression, because they are more easily discussed and more accepted by

society. Addressing these issues will have an impact on the health of your loved one

and on the family unit.

Surveys, interviews and books telling life stories reveal that polio survivors, in general,

credit their acute polio with building character and developing the habit of working

hard. It also taught them to appreciate others and increased their awareness and

insights contributing to their spiritual growth. The literature notes a minority who

clearly express that having had polio is the cause of their bitterness and pain.

The changes that inevitably come with aging can lead to social isolation. Thinking back

about the polio experience can be emotionally upsetting. Both social isolation and emo

-

tional reactions to the late effects of polio are common. Post-polio support groups

that meet face-to-face or online can help, as well as individual and family counseling.

National Institutes of Health Wellness & Lifestyle

National Institute of Mental Health

Support Groups, with their usual meeting schedules,

and resource individuals.

Online discussion lists with a short description of their focus.

more ...

16 Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends

I

s your family member struggling with finding out that he or she has PPS? Does

he or she appear to be in denial about what seems to you to be obvious changes

in his or her functioning? Many polio survivors have difficulties adjusting to new

disabilities. Some people with PPS find that they are now reliving their childhood

experiences with polio and that can be traumatic and even terrifying.

Because of the relatively small number of polio survivors, many physicians see very

few, if any, and know very little about PPS. Some still believe that the condition is

only in their patients’ heads. People with PPS often depend on their own resources

to help them cope with this condition, because there is a lack of proper medical and

psychological advice.

Fortunately, PPS continues to gain attention in the medical community. A growing

number of health care professionals understand PPS and can provide appropriate

medical and psychological help. In addition, there are PPS support groups, newsletters

and educational networks, such as Post-Polio Health International, that provide up-

to-date information about PPS while offering individuals the knowledge that they are

not alone in their struggle.

A. Polio: The Experience

Many polio survivors have never shared their experiences with anyone, even their

children. You may not have known that your parent even had polio until he or she

began to experience the late effects. Why would your family member never have

talked about something that seems so important?

The polio experience was a difficult one. Polio carried a stigma similar to HIV/AIDS

in that others were afraid to associate with children with polio and their households.

It was common for polio survivors discharged from the hospital or rehabilitation to

be discouraged from talking about what they had experienced. If they were able to

pass as non-disabled, polio soon faded from their awareness. Many didn’t feel that

polio had really affected them very much at all until they developed PPS.

However, it did affect them. Acute polio was an extremely painful disease. Along with

the pain, the patient would have a high fever and become unable to move parts or

all of his or her body. He or she may have developed difficulty in breathing, and even

been placed in an iron lung. Children and adults who were hospitalized and contagious

were kept in isolation from family, and even when rehabilitating allowed few visitors.

Professionals thought young children did not need an explanation of what was happen-

ing to them. Young polio survivors were confused and afraid, sometimes believing

they had done something bad to make their parents leave them. There were few

mental health professionals on polio wards to help patients deal with their emotions,

III. Late Effects of Polio: The Psychosocial

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends 17

and those who did do such work didn’t acknowledge the psychological effects of

the illness.

The experience, of course, affected children in many ways. For some, especially those

who had polio before the age of 4, it became hard to trust and connect with others.

Some became mistrustful of doctors and medical treatment. Certain sights, sounds or

smells may bring back the polio experience years afterwards.

When it was time to go through rehabilitation, polio survivors were encouraged to

work as hard as they could, often pushing themselves past the point of exhaustion to

regain as much mobility as possible. They learned to do whatever they could to func-

tion in a society that would make no accommodations for their disabilities. Wherever

possible they were encouraged to give up braces and crutches as soon as they were

able. Essentially, the message was that if they worked hard enough they could be

successful at whatever they wanted to accomplish.

Polio survivors, especially the youngest ones, often returned to the hospital for sur-

geries for many years afterwards. Some children spent every summer in the hospital

having “corrective” surgeries that often did little to improve their functioning. Many

came to dread summer. Some felt they were in constant need of “correction” and

that they were never good enough as they were.

Polio survivors often became stubbornly independent because of these experiences.

They learned to be self-reliant. They exercised and exercised out of a belief that

doing so would allow them to preserve their abilities. For many, PPS has felt like a

betrayal, because what was helpful then has turned out to be harmful now.

Emotional Bridges to W

ellness (Post-Polio Health, 2001)

A Guide for Exploring Polio Memories (Post-Polio Health, 2002)

Improving Quality of Life: Healing Polio Memories (Post-Polio Health, 2002)

more ...

B. Models of Disability/Identity Issues

After polio, survivors learned to cope with their disabilities. Researchers identified

three coping styles that polio survivors used during the initial rehabilitation. Men and

women with mild disabilities who could give up their braces and crutches could “pass”

as nondisabled. Persons who couldn’t do this played down their use of crutches or

braces and magnified physical or personal strengths, thereby “minimizing” the more

obvious effects of the disease. Persons who used wheelchairs or ventilators faced the

architectural and attitudinal barriers of the times. They couldn’t pass nor minimize,

and so fully “identified” with their disability. Many identifiers became leaders of the

independent living movement that resulted in changes in society, including the passage

of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

How your family member deals with PPS depends on how they coped with their

original polio. Identifiers don’t question who they are now even though they are dis-

tressed by new disability. The changes brought on by PPS distresses mostly minimizers

and passers. They may experience a sense of being a different person now, and may

have to deal with what it means to be a person with a disability. For some, counseling

or psychotherapy can help with these concerns.

C. Coping with Stress and Physical Changes

Is your family member having trouble coping with PPS? Individuals who are coping

well focus on what they can do, rather than on what they cannot do, and play an

active role in their lives, rather than respond as passive victims. They participate in

areas of life seen as worthwhile and meaningful. They may have problems, but they

are not overwhelmed by them.

People who are coping well appreciate their accomplishments and do not deprecate

them because they do not meet some “normal” standard. They participate in valued

activities and enjoy doing so. When they have problems, they solve them by making

changes in their physical and social environments, such as eliminating architectural

barriers in their homes and making new friends. They do not wait for a “cure” to

fix everything.

To cope well with increased limitations, polio survivors may need to make important

realistic value changes. They cannot deny their disability. Persons who successfully

cope with their disability enhance their ability to change and to maintain relationships.

The late effects of polio can be complex and distressing as it may arouse painful

memories that may interfere with the need to make major lifestyle changes. However,

survivors often realize that changes, at their own pace, are manageable. They can use

their coping skills to adjust.

Working hard to meet goals and surmount adversity are characteristics of the “polio

tradition.” Your family member has coped with many difficult life experiences. With

support, he or she can cope with these new challenges.

D. Relationships: Families and Friends

As family members become more disabled, they may become more isolated from you,

other family members and friends. They may be less able to attend functions or engage

in activities. Others in your social circles may not know how to deal with a person

with a disability. If your parent has cognitive changes, this makes communication

harder. Polio survivors’ independence can also pose challenges for those around them.

Everyone needs support from family and friends. If you can help loved ones keep

their relationships, and even find new ones, you will help them to have the best possi-

ble quality of life. Offer to help them find ways of getting together with friends and

family, such as using senior or paratransit services, or provide rides yourself.

18 Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends 19

Encourage them to have friends or family over. On the other hand, help your family

member use other means of connecting, such as the telephone or computer. Aged

parents might enjoy getting out to the local senior center. There are many activities

available for all interests and usually transportation. Support groups for PPS or other

issues might help them feel less isolated.

Every relationship is unique, but for any relationship to succeed, both individuals will

need to cope with any disability. This requires a realistic acceptance of the disability

with an emphasis on what one can do, rather than on what one cannot do.

Caring for an aging parent or spouse can strain a relationship. Here are some sugges-

tions on how to keep a relationship healthy.

Accept yourself and your family member. He or she is probably not going to

change at this time of life.

Be actively concerned with each other’s growth and happiness.

Commit to the relationship and to the other person.

Communicate clearly with each other.

Deal with feelings.

Provide freedom and time away from each other.

Be realistic about demands on each other.

Be flexible and adaptive in confronting new challenges.

Be prepared to accept new roles.

If you are having difficulty with a family member or your role as caregiver, or if these

ideas bring up new issues, seek professional help. Support groups for caregivers are

available and can help family feel less isolated.

A. Pain

Pain in muscles and joints is a major issue for people with PPS and typically, the first

or second most common symptom reported to health professionals. Pain can be due

to any number of factors and polio survivors who are experiencing pain should under-

go a comprehensive evaluation to diagnose its cause. Successful management strategies

focus on improving abnormal body mechanics and postures, supporting weakened

muscles with bracing, trying targeted exercises, and promoting lifestyle changes, e.g.,

weight loss, that improve health and wellness and prevent further episodes of pain.

It is possible to reduce or eliminate the vast majority of pain symptoms once the

underlying

cause has been determined, and if the individual is willing and able to make

recommended

changes. Total relief of pain is usually difficult to achieve due to the

continued stress and strain associated with activities of daily living.

Post-polio health care professionals describe three different types of

pain in polio survivors.

Biomechanical Pain

Pain that results from poor posture is the most common type of pain reported by

polio survivors. Weakness in polio-affected muscles (particularly the legs) often leads

to poor muscular balance and skeletal alignment. Years of walking on unstable joints

and tissues makes polio survivors more likely to develop degenerative joint disease.

Nerve compression syndromes like carpal tunnel at the wrist and “pinched nerves” in

the neck and back may develop from years of altered body alignment.

The treatment for biomechanical pain is improving posture and body mechanics to

help decrease the stress on unstable or degenerating joints. Simple adaptations recom-

mended by a qualified health care provider, such as a physical therapist, can modify

posture. The table below provides suggestions to improve common alignment issues,

which can cause biomechanical pain.

20 Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends

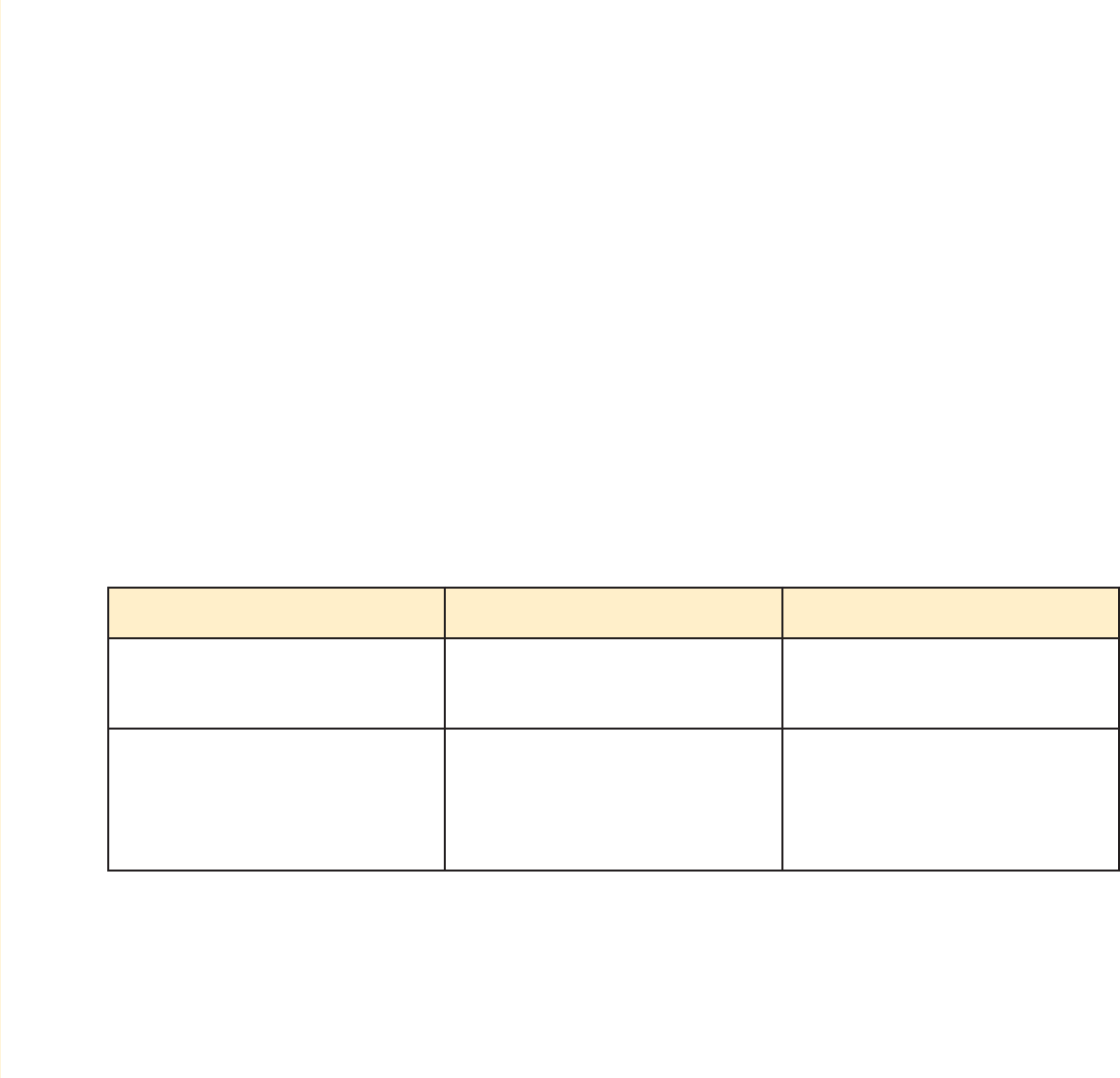

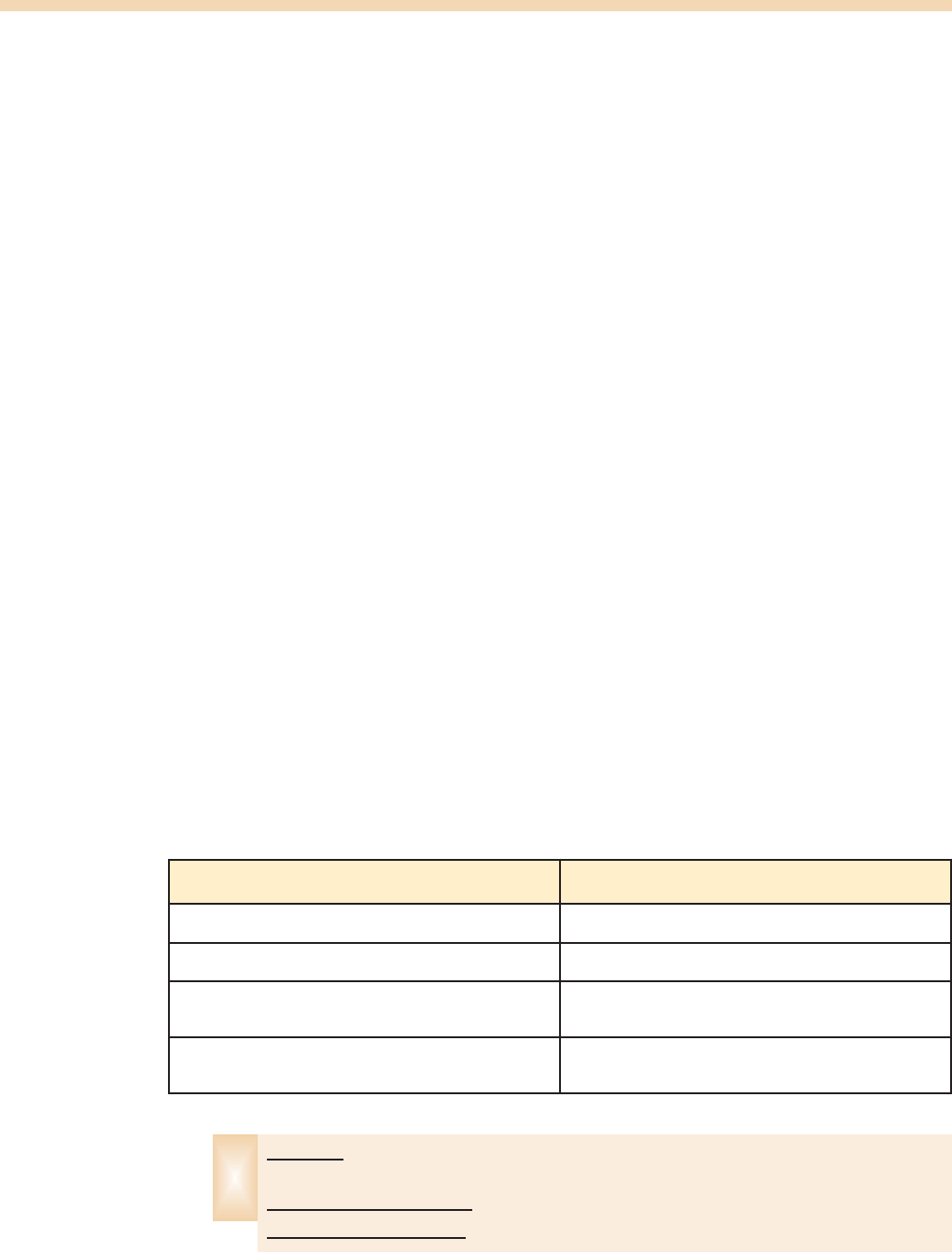

Biomechanical Pain

Problem Ideas to Improve Alignment

Knee pain from “back knee” in the weak leg or in the

“good” leg from overuse

Brace for “back knee”; use of cane to unload stress

on “good” knee

Low back pain due to abnormal leaning to one side

when walking (result of one-sided hip weakness)

Cane held in opposite hand to increase stability and

reduce leaning

Carpal tunnel from using a cane Use ergonomic handles or two canes to minimize

stress on painful wrist

Poor sitting posture due to hip muscle imbalance (one

side is smaller than other)

Small portable pad placed under buttock when sitting

IV. Management/Treatment Ideas

If a polio survivor is reporting pain with repetitive activities or positions (standing,

sitting, walking long distances, etc.), the pain may be due to poor biomechanical align-

ment. Encourage them to seek the assistance of a health care provider knowledgeable

about post-polio syndrome. Avoid encouraging your loved one to “push through the

pain” as this may actually increase their discomfort.

Overuse Pain

The second most common type of pain reported by polio survivors is pain that is

due to overuse of soft tissue. Muscles unaffected by polio, as well as those only mildly

affected, and tendons, bursa and ligaments are all vulnerable to overuse pain. These

structures are often overused to accommodate for weakened polio muscles resulting

in strains, sprains and inflammation. Tendinitis, bursitis and myofascial pain are exam-

ples of painful overuse conditions. The table below offers two examples of painful

conditions that may develop and ideas for solving them.

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends 21

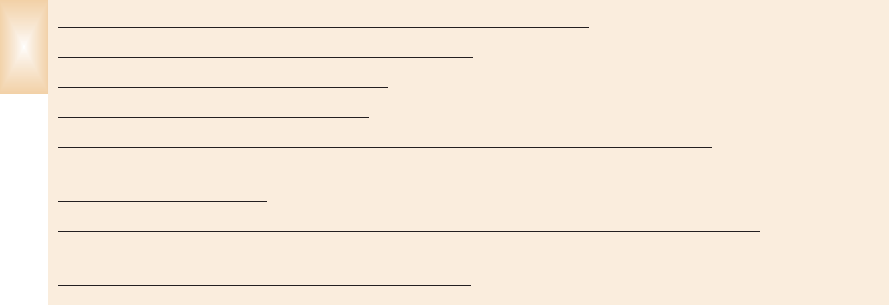

Overuse Pain

Example Problem Activity Ideas to Reduce Pain

Shoulder (rotator cuff) injury from

pushing up body weight using arms

Getting up/down from chairs,

toilets

Elevate seat height

Install/use grab bars

Upper arm muscle pain (biceps

tendinitis) from pulling body weight

up stair rails (due to leg muscle

weakness)

Climbing stairs, e.g., to bedroom

Move bedroom to first floor

Install stair lift

Treatment for overuse pain includes rest and support for the overused body part.

Physical agents such as ice or heat, ultrasound and transcutaneous electrical nerve

stimulation (TENS) may help reduce the symptoms. Modification of the activity that

causes the pain is the best way to provide long-lasting relief. Often rest is not possible

since many survivors rely on upper extremities for both getting around and self-care.

If it is impossible to give complete relief to parts of the body, then encourage pacing.

Many polio survivors need to be convinced to slow down. Let them know it is OK

that certain jobs are unfinished. This is a good time for all of you to observe what is

being done, by whom and how. Is there a better way? In rare cases, steroid injections

or surgery may help.

If your loved one is experiencing overuse pain, encourage them to seek the assis-

tance of a health care provider knowledgeable about post-polio syndrome. Again,

avoid encouraging them to “push through the pain” as this may actually increase

their discomfort.

Post-polio Muscle Pain

Survivors describe post-polio muscle pain as burning, cramping or a deep ache. This

type of pain is usually associated with physical activity and typically occurs at night

or at the end of the day. Muscle cramps and/or fasciculations (muscle twitching) are

indications of overuse of polio muscles. In the table below, you will find a few exam-

ples of how to reduce post-polio muscle pain.

22 Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends

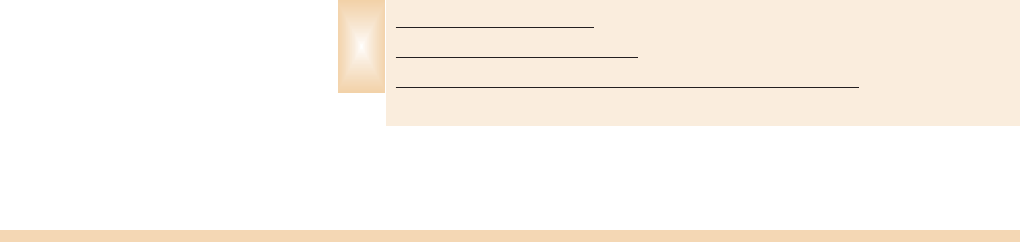

Post-polio Muscle Pain

Muscle Problem Activity Strategies

Front of the thigh (quadriceps) Standing for long periods

Alternate sitting and standing

Evaluate for orthotics, assistive

devices, etc.

Do stretching exercises to help

change position

Calf (gastrocsoleus) twitching or

pain

Walking long distances

Reduce walking distances

Evaluate for orthotics, assistive

devices

Pain in Post-Polio Syndrome (Post-Polio Health, 1997)

Pain (PHI’s Handbook on the Late Effects of Poliomyelitis for Physicians

and Survivors)

How to manage pain (The Post-Polio Task Force, 1997)

Successful Bracing Requires Experience, Sensitivity (Post-Polio Health, 2010)

more ...

Survivors and health professionals use a variety of medications to treat post-polio

muscle pain. The most common ones tried are of little use. Examples include the

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDS – aspirin, ibuprofen and naproxen),

acetaminophen (Tylenol), benzodiazepams (Xanax, Valium) and narcotics.

Experience shows that tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), especially amitriptyline, can

help with easing pain and decreasing fatigue.

Decreasing activity of the painful muscle(s) throughout the day is the best way to

manage post-polio muscle pain. An evaluation for the need for orthotics (braces)

and/or assistive devices (canes, crutches, scooters) and their appropriate use may also

help to reduce post-polio muscle pain.

If you notice that your loved ones is complaining of pain at the end of the day or if

you notice muscle twitching in polio muscles accompanied by pain, the cause of the

pain is most likely from overuse of the polio muscles and the best course is decreas-

ing activity throughout the day.

B. Weakness

New muscle weakness is the hallmark of PPS and is associated with the effects of

aging on muscles already weakened by the effects of polio. New muscle weakness is

more likely to occur in muscles most affected during the acute poliomyelitis. How-

ever, occasionally “previously unaffected” muscles may also develop some new weak-

ness. Polio could have affected “previously unaffected” muscles during the initial ill-

ness, but the new weakness is not apparent until aging makes it evident.

As a rule, new muscle weakness parallels a decline in a polio survivor’s ability to do

certain activities. For example, a decrease in strength of the quadriceps (front thigh

muscle) may correspond with increased difficulty climbing stairs or walking long dis-

tances. Individuals may also experience problems with breathing and/or swallowing.

The course of new weakness is variable with some individuals experiencing a slow,

continuous progression while others report a stepwise course with plateaus between

periods of progression.

Disuse weakness may occur if there has been a change in lifestyle and the individual

has been more sedentary. For example, a change in work responsibilities or a recent

hospitalization may result in this type of weakness. A trial of carefully monitored

exercises may improve the strength in muscles with disuse weakness.

Pacing and Bracing

To manage new weakness, generally it is important to stop overusing weak muscles by

pacing activities and using assistive devices and/or braces. Research demonstrates that

non-fatiguing exercise programs can improve the strength of mild to moderately weak

muscles. However, new muscle weakness in polio survivors is frequently not due to dis

-

use weakness. The important point in managing new weakness is to avoid frequent

or continuous muscle overuse, or muscle exhaustion, and to use a non-fatiguing

exercise program.

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends 23

Weakness (PHI’s Handbook on the Late Effects of Poliomyelitis for Physicians

and Survivors)

How to manage weakness (The Post-Polio Task Force, 1997)

P

rescription for Weakness (PHI’s Fifth International Conference, 1989)

more ...

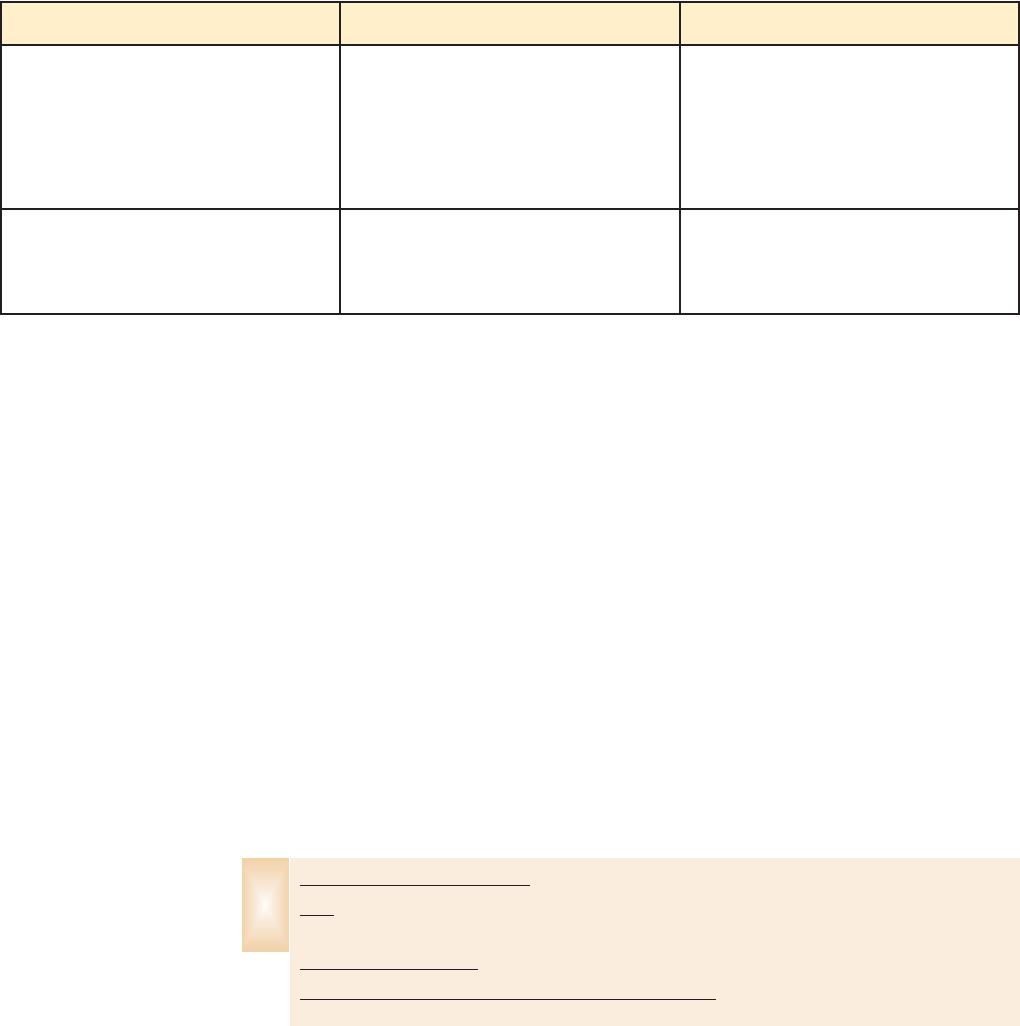

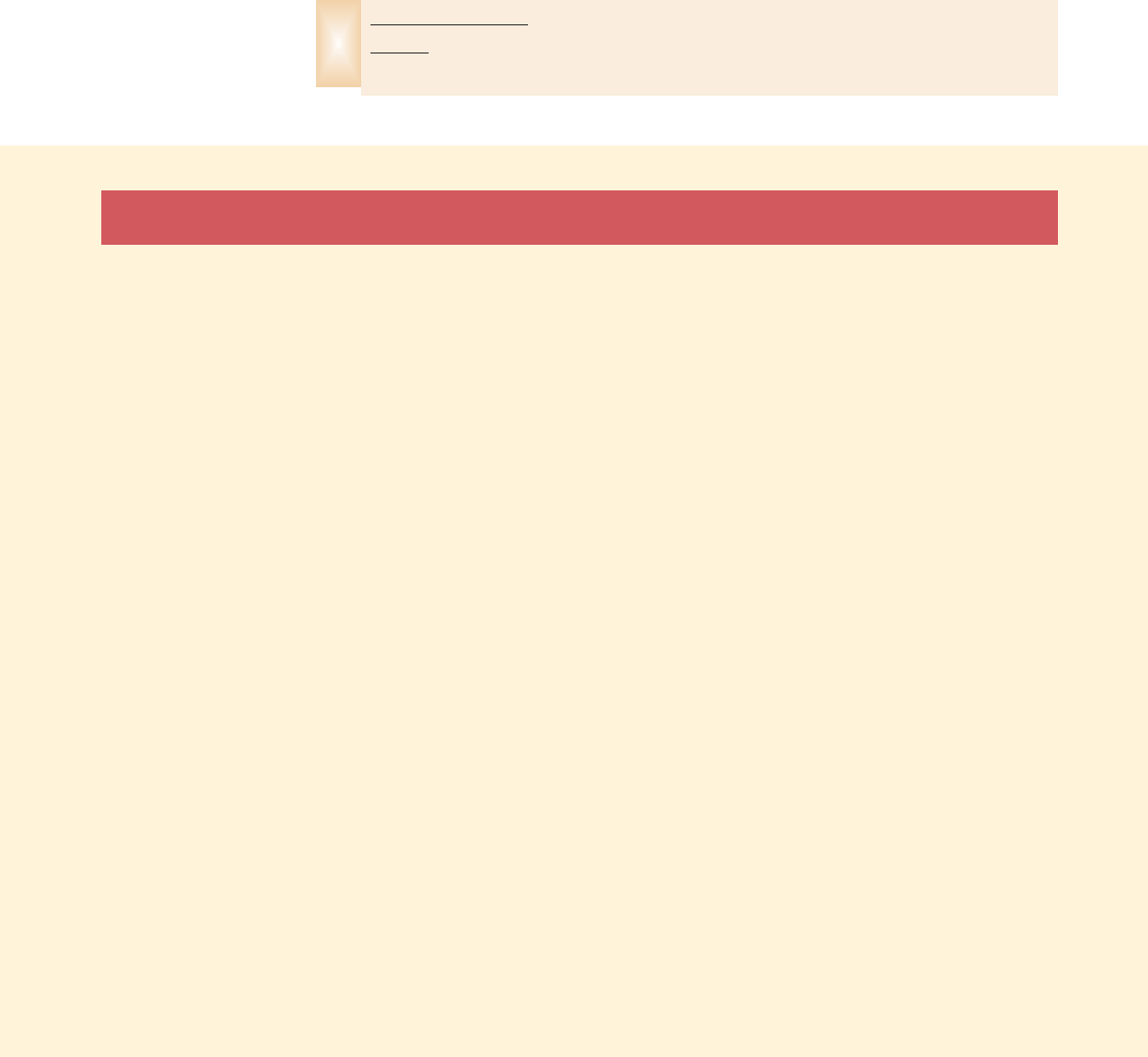

New Muscle Weakness

Problem Possible Adaptation

Getting on/off toilet/couch (leg weakness) Elevate toilet; Use arm rests with push off

Long distance walking Manual or power wheelchair or scooter

Foot drop or slap when walking (weakness

in ankle muscles)

Ankle foot orthosis (AFO brace)

Choking, swallowing problems Soft food diet, smaller bite size, refer to

swallowing study

C. Fatigue

Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms expressed by polio survivors with a

variety of possible causes. Fatigue is a nonspecific term that polio survivors often use

to describe decreased muscle stamina and endurance. Survivors also describe a global

or generalized exhaustion that can affect mental alertness. Many polio survivors

describe a major decrease in stamina following illness, surgery or trauma, and recovery

may take three to four times longer than for people without prior polio.

To treat fatigue adequately, first identify the contributing factors. For example, many

medical conditions may result in fatigue. Some of the more common medical disorders

associated with fatigue include anemia, diabetes, thyroid disease, fibromyalgia and

depression. Dealing with disability and lost function is emotionally draining for many

and can lead to depression with decreased attention, decreased ability to concentrate

and increase in fatigue.

Fatigue occurring upon awakening usually reflects sleep disturbances that can be the

result of a variety of conditions including musculoskeletal pain, restless leg syndrome,

or respiratory abnormalities, such as sleep apneas and difficulty breathing due to spinal

curvatures. Survivors may have new respiratory muscle weakness, which results in

inadequate breathing and ultimately excessive fatigue.

Prescription medications such as beta-blockers and sedatives contribute to feelings of

fatigue. Narcotics used for treatment of chronic pain may also disturb sleep and can

contribute to a feeling of fatigue and irritability.

Chronic musculoskeletal pain can also lead to deconditioning, another contributing

factor to general fatigue. While staying “in shape” or “in condition” is important,

each survivor must find the balance between overworking polio muscles and appro-

priate conditioning exercise. A safe approach is for survivors to start a realistic super-

vised exercise program and slowly add additional exercises and repetitions to it.

The management of fatigue follows many of the same principles as interventions for

weakness and pain. Thus, improving one symptom will often result in an improvement

in others.

It is important first to identify what is contributing to the fatigue. Many health care

providers use a fatigue scale to establish a baseline score or a survivor’s current type

and level of fatigue. They use the scale again to measure how beneficial their sugges-

tions, such as braces, canes and breathing machines, are. With time and persistence,

most people DO feel better.

You should encourage your parent or friend to make meaningful changes in their

daily activities to help reduce fatigue.

24 Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends

Fatigue (PHI’s Handbook on the Late Effects of Poliomyelitis for Physicians

and Survivors)

How to manage fatigue (The Post-Polio Task Force, 1997)

When Do You Need a Power Chair? (Post-Polio Health, 2010)

more ...

D. Breathing and Swallowing Problems

Many of the urgent requests PHI receives are from family members who call because

their loved one suddenly ends up in the hospital on a ventilator. The key is to be

prepared.

It is critically important for the families to be on the lookout for sleep and breathing

problems in their parent or loved one, especially those who were in an iron lung or

who “just missed being in one.” Symptoms to watch for include:

sleeping best while sitting in a chair or a recliner,

becoming breathless while doing a little extra walking, work, etc.,

noticing that a significant curve of the spine is getting worse,

observing extreme grogginess, confusion and/or headaches in the morning that

“goes away” after an half-hour or so,

falling asleep during the day during unusual times, e.g., at a stop light, during

a conversation, and

having repeated bouts of bronchitis or pneumonia that can be related to a weak

cough or to food entering the lungs (aspiration pneumonia).

As your loved one ages, respiratory muscle (e.g., diaphragm and those connected to

the ribs) strength may decrease. It is particularly evident when lying down, because in

this position, the diaphragm has to work harder both to pull air in and to push the

intestines and other abdominal organs out of the way. These are generally out of the

way when one is upright due to gravity.

Polio survivors with weak abdominal and chest muscles can’t cough as effectively and

may experience more episodes of bronchitis or pneumonia. Sometimes health profes-

sionals treat the pneumonias and bronchitis as they should, but may not determine

and address the cause – respi

ratory muscle and coughing muscle weakness. Remember

that with polio, there is generally nothing

wrong with the lungs themselves, but with

the muscles that enable the lungs to function properly.

Testing in these situations should include pulmonary function tests, which are mostly

noninvasive. They measure the forced vital capacity (FVC) and consequently the

strength of respiratory muscles by measuring the maximum amount of air one can

exhale. Note: Typically, a person is administered this test while sitting in the upright

position, but request that it also be administered when your loved one is lying down

for reasons explained above. When looking for professional medical help, look for a

pulmonologist who specializes in neuromuscular diseases, i.e., ALS, MD, etc., versus

one who only treats diseases of the lungs.

Unfortunately, many articles written about sleep and breathing problems in polio sur-

vivors only mention obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). In obstructive sleep apnea, the

upper airway collapses and blocks the flow of air so the person stops breathing peri-

odically. Signs of OSA are snoring and daytime sleepiness. A sleep study can detect

apneas and hypopneas (breathing lapses). Four percent of women and 9% of men

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends 25

nationwide experience obstructive sleep apnea, and at least that many polio survivors

do. (Many sleep specialists think these estimates may be too low.)

Survivors also can have central sleep apnea (CSA), a condition in which the brain

temporarily “forgets” to signal breathing muscles to take a breath. This is evident dur-

ing a sleep study when there is no chest movement for at least 10 seconds, indicating

that the individual is not breathing. Some people have mixed sleep apnea, which is a

combination of OSA and CSA.

The solution for those with only obstructive sleep apnea is a CPAP machine – a

machine that continuously blows in air through a mask worn at night or during sleep.

This constant airflow keeps the airway open, so one can breathe easily.

Polio survivors who have central or mixed sleep apnea or significant respiratory muscle

weakness use a bi-level device (one that blows air in at a certain pressure when inhaling

and at a lower pressure when exhaling through a mask over the mouth or nose). Others

use a volume ventilator or one of the newer multi-mode devices. There is a wide variety

of masks and breathing devices available on the market. Experienced pulmonologists

and respiratory therapists can assist in obtaining the correct treatment and equipment.

Although your parent or loved one may not have breathing or sleep problems when

initially checked, periodic testing is important because such problems may develop

over time.

They may begin to complain of difficulty swallowing. Complaints include food sticking

in the throat, difficulty swallowing pills, coughing spells during eating, food backing

up from the throat, taking longer eating a meal and unintentional weight loss.

Because many of the muscles and nerves that control swallowing also control speech

and voice, changes that make swallowing more difficult may also make speech more

difficult, and quieter and harder to hear by others.

Swallowing problems that put a person at risk for aspiration – where food enters the

airway instead of the stomach – can result in bronchitis and pneumonia. The two pri-

mary tests for checking swallowing are the modified barium swallow and a fiberoptic

swallowing examination of the throat. Your parent’s primary physician or pulmonolo-

gist can refer them to a speech-language pathologist (someone who specializes in

swallowing problems, referred to as dysphagia) at a hospital or a rehabilitation center

for evaluation and treatment.

26 Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends

My Journey through the Basics of Post

-Polio Breathing Problems (Post-Polio Health, 2007)

P

ost

-Polio Breathing and Sleep Problems Revisited (Post-Polio Health, 2004)

Cardiovascular Issues of P

olio Survivors

(Post-Polio Health, 2001)

Breathing P

roblems of Polio Survivors (Post-Polio Health, 2001)

Hypoventilation? Obstructive Sleep Apnea? Different Tests, Different Treatment

(Ventilator-Assisted Living, 2005)

What Is Hypoventilation? (Ventilator-Assisted Living, 2003)

Airway Clearance Therapy for Neuromuscular Patients with Respiratory Compromise

(Ventilator-Assisted Living, 2002)

Swallowing Difficulty and The Late Effects of Polio (Post-Polio Health, 2010)

more ...

E. Depression and Anxiety

Are you worried that your family member may be depressed or anxious? Everyone

feels “blue” or “worried” or “scared” sometimes. Everyone says, “I’m depressed” or

“I’m anxious” at times. This may be just a passing feeling. It may be because of some

-

thing that is happening at the moment.

For example, it is normal to feel sad when someone you love dies or when you lose

something that matters to you. Elders often have lost many of the important people

in their lives, and may be grieving these losses. They may be grieving because they can

no longer do things they love.

Normal sadness or grief is not the same as depression, even though the person having

it may say, “I’m depressed.” In addition, normal fears are not the same as anxiety dis-

orders like panic, phobias, generalized anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.

If your parent or spouse is sad or worried and friends and family aren’t able to help,

they could get help from talking to someone such as a psychotherapist, physician

or

clergy.

Medication would not be appropriate or helpful and might even be harmful.

However, depression is different from sadness or grief. It is a serious condition and

needs to be treated. With proper help, including psychotherapy and possibly medica-

tion, your family member can recover. Obtain a consultation with a qualified behav-

ioral health professional if he or she has four or more of the following symptoms

for more than two weeks.

Persistent sad, “empty,” or anxious mood.

Loss of interest or pleasure in ordinary activities, including sex.

Decreased energy, fatigue (different from PPS fatigue), being “slowed down.”

Sleep disturbances (insomnia, early-morning waking, or oversleeping).

Eating disturbances (loss of appetite and weight or weight gain).

Difficulty concentrating, remembering, making decisions (in elders, this can look

like dementia).

Feelings of hopelessness, pessimism.

Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, helplessness.

Thoughts of death or suicide, suicide attempts.

Irritability.

Excessive crying.

Chronic aches and pains (not attributable to PPS or related conditions) that do not

respond to treatment.

Just as it is normal to feel sad when sad things happen, it is also normal to feel anxiety

or fear over things we can’t control, when changes happen to us or to others around

us, or when frightening things happen. Someone whose health or physical abilities are

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends 27

changing may express fear about the future. (Some people have always been worriers

and will always find things to worry about no matter how good life seems to be.)

Anxiety disorders are different from these fears. Signs that your family member may

be suffering with an anxiety disorder are not limited to but include:

Excessive worrying.

Fears that seem excessive or unreasonable.

Panic attacks.

Fear of leaving the house (other than because of accessibility or mobility concerns).

Compulsions (hand-washing, hoarding, counting, checking).

Flashbacks, nightmares or intrusive thoughts of traumatic experiences.

There are effective treatments for anxiety disorders that include psychotherapy and

medications. Consult a behavioral health provider or your parent’s physician for

more information.

F. Trauma

Injuries from accidents, particularly falls, are common among aging polio survivors

who may be slowly weakening. Even though polio survivors were taught “how to fall”

during rehabilitation from the acute polio and may have fallen frequently most of

their lives, do not dismiss or minimize the danger of falls.

Serious injuries, such as fractures and joint dislocations, and lesser injuries, such as

sprains, strains and bruises, may all require a long period of not using a limb to allow

for healing.

Both injuries to bones, joints and muscles and severe illnesses, including major surger-

ies, can result in long periods of being in bed and/or being much less active than

usual. Inactivity for even several days may result in enough new muscle weakness

and/or loss of energy to make your loved one unable to move about in their usual

ways and can threaten independence.

The medical name for this type of muscle weakening is “disuse atrophy,” and the

name for the loss of energy is “deconditioning” or “getting out of shape.” Both of

these conditions begin more quickly, worsen more and are harder to reverse for polio

survivors than for people without nerve or muscle problems.

Clinicians have observed that the recuperation period after surgery, severe illness or

injury is at least three to four times longer. Survivors are at risk of additional strain

28 Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends

Recognizing Depression (Post-Polio Health, 1999)

Treatment Approach Options (Post-Polio Health, 1999)

Pursuing Therapeutic Resources to Improve Your Health

(Post-Polio Health, 2002)

more ...

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends 29

V. Evaluation of Options within the Family

F

rom the Inside Out (Post-Polio Health, 2004)

T

rauma (PHI’s Handbook on The Late Effects of Poliomyelitis for Physicians and

Survivors)

more ...

injuries during post-injury periods because they are doing things differently, i.e., have

to put most of their weight on one leg after knee surgery. Post-injury rehabilitation

efforts may also cause strain on muscles and joints. During severe injury and illness,

survivors may experience new breathing difficulties from respiratory muscle weakness

that was not evident before.

It is not surprising that about one-third of polio survivors report the onset of “pro-

found fatigue” and/or “post-polio decline” during a period following illness, surgery

or trauma. Minimizing the time of inactivity and planning for a longer and more care-

fully supervised period of rehabilitation and/or recuperation after traumatic injury

can be very helpful. Paying attention to inactivity and over-strenuous rehabilitation

activity is often crucial for post-polio survivors to make a full recovery to the pre-

injury/illness level of function.

W

hen polio survivors experience illnesses or loss of physical ability requiring

significant care and/or major changes in lifestyles, their families make major

decisions. The best scenario for family members is that polio survivors have

already honestly communicated their experience of having had polio and have com-

pleted the necessary forms designating someone power of attorney for health care

and that the papers are readily available. However, if forms for power of attorney for

health care are not completed, the following information should help you as your

family unit navigates through the decision-making process, or as the group works

together to do what is best for all concerned.

Effective communication is key to making solid decisions collectively. Communica-

tion styles vary within cultures and families. Some families consider it inappropriate

to communicate honestly and directly. In other families, such as when a parent

had/has an addiction, family members may not have felt safe speaking the truth for

fear of reprisals.

Effective communicators attend to the nonverbal aspects of space, energy and time as

well as to their choice of words and actions as they move from situation to situation.

Effective communicators are honest, clear and sensitive, showing support and respect

for other members of the family.

During discussions, it is good to remember that you only have control over what you

can realistically do – how you communicate, listen and respond to the other person.

You cannot control how the other person responds.

30 Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends

Beginning a statement with “I” rather than “you” is a straightforward approach that

invites open and direct exchanges. Saying “I disagree” rather than “You’re wrong” is not

blaming or accusatory, and as a result, can reduce defensiveness and conflicts.

During a crisis or when discussing the future of aging polio survivors, children and

spouses

can struggle with anticipatory grief – a feeling of loss before a death or

dreaded event occurs.

Anxiety and dread are the worst symptoms. Hospice groups

have developed suggestions for dealing with anticipatory grief, e.g., talk with a trusted

friend, give yourself permission to cry, keep a diary, utilize your hobbies, etc.

Out of necessity, many polio survivors have been “in control” of their activities and

surroundings. They have mastered the art of thinking ahead and planning for all pos-

sibilities. When they are ill and no longer able to fulfill that role, others notice a gap

and the family decision-making process changes.

PHI’s survey revealed that many survivors are confident that their spouses who have

for years accompanied them to physicians’ appointments are well equipped to advo-

cate for them. Children of survivors who have been through a crisis with their parents

have issued a caution regarding aged spouses. Their intention to be involved with health

care decisions and actual personal care of their loved one can be curtailed by their

own health problems and overwhelming emotional feelings. The spouses may

need

the support of their children to be the advocate the polio survivor wants them to be.

Polio survivors in our survey were clear that as long as they were able to make decisions

they wanted to make them. They wanted to be given options and to be involved in all

of the decisions, and didn’t want their families to “give up” on them. Noting that their

families watched them closely, one stated, “I sometimes worry about what’s happen-

ing to me that is invisible to them.”

A few didn’t want to “be a burden” to their children and indicated that they could do

it alone, or with their spouse’s help. While admirable, this attitude may not be realistic

or even beneficial to the family’s emotional health.

One daughter revealed the challenging times she faced as she and her father changed

roles. She found that “the more Dad revealed to me about his experiences as a boy, the more

I understood the reasons for his strong reactions. Then I was able to provide him with comfort

and support.”

Some polio survivors have an aging parent who can become very distressed during a

medical crisis of their child who had polio at a young age. This parent has unresolved

guilt about their child “getting polio” and new illnesses spark these feelings.

Lastly, another important family dynamic is the relationship among siblings. The chil-

dren who live the closest in most cases assume the bulk of the practical day-to-day

responsibilities. Tension can arise when brothers and sisters from afar offer well-

intended suggestions to those already overworked. Conversely, some children with the

major responsibility can feel abandoned if their siblings don’t show enough interest.

Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends 31

VI. Professional Assistance

Each family needs to find its own balance. Putting yourself in the other’s shoes is a

good place to start.

One wise survivor stated, “Complaining is not an effective strategy.”

Effective Family Communications: Do We? How Can We Improve It? (PHI’s 10th

International Conference, 2009)

Family Communications Worksheet (PHI’s 10th International Conference, 2009)

Not Going Is Not an Option (Post-Polio Health, 2010)

more ...

M

any polio survivors feel that health professionals are unprepared to treat

them and carry with them a level of distrust. Because of passage of time, it

is unreasonable to lament that my physician “never saw the original polio.”

Asserting, “post-polio is never taught in medical school” is counterproductive.

Medical schools teach about the acute polio infection and that it results in residual

weakness. In the past, health professionals thought that polio weakness was static or

stable, but most professionals today know from research and observation that it can

be slowly progressive.

Many physicians are aware that there can be new weakness, but they have not seen it

in many of their patients. In fact, many have never treated a person who had polio,

which is why PHI makes resource materials readily available to both health profes-

sionals and lay people.

While some of the lay post-polio literature emphasizes the uniqueness of the medical

problems of polio survivors, it may be overemphasized. The advice and procedures

for treating common medical problems for those who did not have polio are the same

for post-polio people. However, it is important to advise medical professionals that your

loved one had polio (a neuromuscular disease), so they can integrate this knowledge

into a treatment plan. If your parent or friend has a “post-polio physician” or a pul-

monologist, who monitors their breathing status, always seek advice from them when

facing other medical issues. Families are encouraged to facilitate actively the connec-

tions between the medical specialists involved in the care of polio survivors.

Start with the family physician. Following is list of other health professionals who you

may call upon.

A. Family Physician

Health care reform is leaning towards the coordinated care model. A primary care

health provider (nurse practitioner, physician’s assistant, family medicine doctor or

internal medicine doctor) most likely will be the coordinator of your loved one’s

health care.

Getting to know a primary care health provider, and them getting to know your par-

ent or friend as a person as well as a patient, can be very valuable and assures prompt

appointments in an emergency. Established patients generally have priority over

unknown patients when the schedule is busy.

Primary care physicians perform certain technical procedures, determine what is

wrong, and offer reassurance, after an annual physical, that many things are very right.

They also provide advice on how to take care of problems or to stay healthy.

Not all primary care physicians know about polio or post-polio. Some are willing to

learn and some are not.

Value a physician who says, “I do not know” and who gets out the books or gets on

the phone and asks someone else. A physician who says they know it all is one to

avoid. (At least 50 different high blood pressure medicines, about 100 different anti-

biotics, and 40 different birth control pills are now available.)

Most primary care physicians schedule a patient every 10 to 20 minutes. Schedule

more time if there are many issues to discuss. Many now have at least one exam

table that goes up and down. Advise them if your loved one will need it, so they can

schedule it.

Write down questions and concerns. Don’t save the most important issues for the

end. It is also helpful to bring a list of medicines and dosages. Take in medicines.

Take in the facts.

It is also useful for the primary care physician to know the number and type of

orthopedic surgeries and the respiratory history, i.e., in an iron lung during the acute

phase of poliomyelitis, use a bi-level device at night, etc.

Some primary care physicians return phone calls and will most likely continue to do

so, if they know that you will respect their time and keep the conversation short.

32 Post-Polio Health Care Considerations for Families and Friends

The Primary Physician (Post-Polio Health, 1995)

more ...

B. Health Care Specialists

There is no official certification for a “polio doctor.” The most common use of this

informal designation is a physician with knowledge, experience and interest in evalua-

tion and treatment of polio survivors.

Given the most common new disabling medical problems of polio survivors, physi-

cians with expertise in neuromuscular disease management that includes the ability to

recognize and treat chronic musculoskeletal pain and respiratory problems are ideal.

The specialty back

ground of these physicians is most commonly neurology, physical

medicine and rehabilitation,

orthopedics and family practice.