THE PSYCHOLOGY OF POLIO AS PRELUDE TO

POST-POLIO SEQUELAE:

Behavior modification and psychotherapy

Richard L. Bruno, Ph.D.¹ and Nancy M. Frick, M.Div.²

Bruno RL, Frick NM. The psychology of polio as prelude to Post-Polio

Sequelae: Behavior modification and psychotherapy. Orthopedics, 1991,

14(11) :1185-1193.

Lincolnshire Post-Polio Library copy by arrangement with the Harvest

Center Library

1. Post-Polio Rehabilitation and Research Service

Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation

East Orange, New Jersey

and

Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

New Jersey Medical School

University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey

2. Harvest Center

Hackensack, New Jersey

Address correspondence to:

Nancy M. Frick, M.Div.,

Harvest Center,

151 Prospect Avenue,

Hackensack, New Jersey 07601

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF POLIO AS PRELUDE TO POST-POLIO SEQUELAE:

Behavior modification and psychotherapy.

Richard L. Bruno, Ph.D.¹ and Nancy M. Frick, M.Div.²

ABSTRACT

Even as the physical causes and treatments for Post-Polio Sequelae (PPS) are being

identified, psychological symptoms - chronic stress, anxiety, depression and

compulsive, Type A behavior - are becoming evident in polio survivors. Importantly,

these symptoms are not only themselves causing marked distress but also are preventing

patients from making the lifestyle changes necessary to treat their PPS. Neither

clinicians nor polio survivors have paid sufficient attention to the acute polio

experience, its conditioning of life-long patterns of behavior, its relationship to the

development of PPS and its effect on the ability of individuals to cope with and treat

their new symptoms. This paper describes the acute polio and post-polio experiences on

the basis of patient histories, relates the experience of polio to the development of

compulsive, Type A behavior, links these behaviors to the physical and psychological

symptoms reported in the National Post-Polio Surveys and presents a multimodal

behavioral approach to the treatment of PPS by describing patients who have been

treated by this Post-Polio Service.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank those who have volunteered as research subjects and

our patients, whose experiences are the foundation of this report and who have allowed

themselves to be quoted for this paper. We would also like to thank Dr. Thomas Galski

for his criticism of the manuscript, Ms. Joan Kelly for her computer expertise and Mary

Ann Solimine, R.N., M.L.S., without whom this work would not have been possible.

This research was funded by grants from the Joel Leff and George Ohl Foundations.

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF POLIO AS PRELUDE TO POST-POLIO

SEQUELAE: Behavior modification and psychotherapy in treating PPS

Richard L. Bruno, Ph.D. and Nancy M. Frick, M.Div.

"I'll walk without crutches. I'll walk into a room without scaring everybody half to

death. I'll stand easily enough in front of people so that they'll forget I'm a cripple."

Franklin D. Roosevelt (1)

In the 1980's, nearly half of the 1.63 million American polio survivors reported new and

unexpected symptoms - fatigue, muscle weakness and pain - that have come to be called

Post-Polio Sequelae (PPS) (2,3). While the medical community focused its attention on

these new physical symptoms, polio survivors' psychological reactions to PPS emerged.

Fear, disbelief, denial and confusion were experienced first since PPS were completely

unexpected (4). The 1985 National Survey of 738 polio survivors (5,6) revealed that

86% of the respondents never considered the possibility of developing new problems

after having reached maximum recovery from polio and that 72% did not initially think

that their new symptoms were related to their having had polio. Since polio survivors

did not know the cause of their new symptoms they looked to the medical community

for help.

Fear and confusion increased as medical ignorance and disinterest frustrated and

angered polio survivors. Many physicians dismissed new symptoms as psychogenic,

factitious or unrelated to polio. In the 1985 National Survey, 23% of respondents were

told by physicians that the symptoms were "all in their minds" while 26% were told that

the symptoms "could not possibly be related to having had polio." Other patients

received frightening and unfounded diagnoses, such as "some kind of ALS" or

recrudescent polio (3). Many patients were told that they would have to accept new

symptoms and loss of function since all polio survivors were "just getting old" (4).

Now, in the second decade of PPS, the medical community has accepted the reality of

PPS and is identifying effective treatments for new fatigue, weakness and pain. Even

with these advances, additional psychological symptoms - chronic stress, anxiety,

depression and compulsive, Type A behavior - are being identified in polio survivors.

Importantly, these symptoms are not only themselves causing marked distress but also

are preventing patients from making the lifestyle changes necessary to treat their PPS

(6,7,8).

It appears that the factor central to the etiology of these psychological symptoms is that

polio survivors are being forced to cope with new symptoms and disability when many

have not yet dealt with the emotional reality of their having had polio over thirty years

ago. Evidence for the postponement of coping with the acute polio experience was

found in the 1985 National Survey, where 26% of respondents reported that they "did

not think of themselves as having a disability" before developing PPS; with the onset of

PPS 42% admitted to having a "second disability." (6)

Neither clinicians nor polio survivors have paid sufficient attention to the acute polio

experience, its conditioning of life-long patterns of behavior, its relationship to the

development of PPS and its effect on individuals' ability to cope with and treat their new

symptoms. It is the purpose of this paper 1) to describe the acute polio and post-polio

experiences on the basis of published reports and patient histories; 2) to relate the

experience of polio to the development of compulsive, Type A behavior; 3) to link

compulsive, Type A behavior to the physical and psychological symptoms reported in

the National Post-Polio Surveys; 4) to present a multimodal behavioral approach to the

treatment of PPS by describing patients who have been treated by this Post-Polio

Service during the past year.

The Acute Polio Experience

Polio survivors frequently report that the onset of PPS have forced them, often for the

first time, to recall and examine their acute polio experience (9). With the onset of polio,

these individuals understood that they had been stricken by the "greatly feared disease,"

believed that disability was likely and death was possible (10). These fears were

amplified in those who knew others who had been disabled or even killed by polio (10).

Polio survivors recall confusion and terror at being wrenched from their homes and

being given by their parents into the care of strangers with whom they were required to

live for weeks, months or even years (11). Even children too young to understand what

was happening likely sensed their parents' fear and panic; they certainly felt the pain of

their own illness and the desolation of being abandoned by their parents (11,12,13,14).

Individuals admitted to hospital quickly became aware of their complete loss of control

and total dependency on the hospital staff. Many could not feed or toilet themselves;

those with the most severe paralysis could not even move. Patients' were forced to rely

totally on hospital staff if their most basic survival needs were to be met. If they were to

survive, patients had little choice but to suppress their fears and follow their parents'

parting instruction: "Be good, don't make trouble and do everything you're told" (11).

Separation from parents and loss of control were not the only sources of fear. Patients

describe a hospital regimen of painful and often frightening therapies including hot

packs, splinting, bracing, stretching and exercise (15). Patients also report undergoing

multiple surgeries, including muscle transplants, tendon lengthenings and osteotomies.

One especially brutal procedure that many parents attempted to obtain for their children,

pulverized weakened muscles and their motor nerves with an electric riveter to promote

axonal sprouting - a uniquely medieval attempt to prevent permanent visible disability

(16,17). These procedures were administered usually without explanation and certainly

without consent since, especially at the height of the epidemics, hospitals were

overwhelmed by the sheer number of polio patients needing care

(10,11,12,13,15,18,19). Excluding young patients from treatment decisions and the

failure to communicate information about their illness magnified the severity of the

illness to the patients and permitted their inherent fear of death to emerge (14).

Questions or complaints about therapies were not infrequently met by staff anger or

punishment (13,18). Staff anger was viewed as a very real threat to survival by patients

who were isolated from parents and totally dependent on the staff. One patient described

this situation as placing her in "mortal danger" (15); she believed that the staff had to be

placated if she were to survive. Patients discovered that staff anger could sometimes be

prevented if they complied with hospital regimen without questions. Full participation

in therapies, without regard to pain or exhaustion, would sometimes garner brief

attention or even praise. Thus, the expression of personal needs and emotion were

punished by the staff while unquestioning compliance with and performance for the

staff were reinforced. Unfortunately, protection from punishment could not always be

assured. Patients describe staff who acted with unnecessary cruelty in maintaining order

and control on the ward. Family visits were restricted to only a few hours per week,

reinforcing patients' feelings of parental abandonment and dependency upon staff

(12,15,20). Normal, child-like behaviors were punished excessively. Several patients

reported having been locked in a completely dark closet overnight when they spoke or

cried after "lights out." Even appropriate and necessary nursing care could be withheld

for no apparent reason (15,18).

Many of the patients treated by this Service have related other instances of

psychological, physical and even sexual abuse at the hands of hospital staff. Instead of

causing patients to complain, such abuse further reinforced patients' belief that survival

depended upon the suppression of personal needs and emotion and unquestioning

compliance with those in authority. This belief is evidenced in one patient's rationale for

not reporting repeated sexual abuse: "I would have made my parents angry because I

was not doing what I was told and the nurses, who I depended on for everything, would

have punished me for making trouble for them. All I could do was stop feeling bad

about it and smile."

Under these circumstances, some patients report having lost their sense of "identity"

(18,20). Some report over-identifying with the staff and even expressed the desire to

become "orthopedic surgeons when they grew up" (21). Others apparently submitted so

completely to the hospital staff that they did not wish to go home or even asked to

return to the hospital following discharge (22,23). It appears that many polio survivors

learned to deal with their abandonment, loss of control, fear, pain and abuse by

submitting to those in authority, complying fully with external expectations and denying

personal needs, physical and emotional pain and even their own individuality (24).

These behaviors are evident in this summary of the "Good Chart" written by polio

wardmates at Baltimore's City Hospital (22):

LISTEN TO THE DOCTORS

OBEY THE NURSES

DO NOT FIGHT

DO NOT BE BAD

BE GOOD IN SCHOOL

DO YOUR HOMEWORK

DO NOT TALK AT DINNER or IN SCHOOL

LITTLE FOLKS SHOULD BE SEEN AND NOT HEARD

When polio patients returned home as "polio survivors," the "Good Chart" became their

prescription for proper behavior. They had learned very young and very well that

submission, compliance and suppression of emotion were required if they were to

escape "mortal danger"(15).

Polio Survivors in the Community

When polio survivors re-entered their communities, any special attention that may have

been provided to them and their families during the acute polio often quickly stopped

(22). Friends of polio survivors' families, unable to deal with the reality of polio, often

disappeared (22). It was not uncommon for neighborhood children to be prohibited from

playing with "polio victims" for fear that the "crippling" was contagious (23). Polio

survivors, no longer physically able to participate easily or fully in social activities,

became isolated (10,25). Such alienation and isolation made polio survivors pariahs

(10,14,22,25).

However, there was "hope." Individuals had been imbued with the "unqualified progress

ideology" of physical therapy following their acute illness and had often been given

prognoses upon discharge that were unrealistically optimistic (26). One paraplegic

woman was told, "You'll walk out of your braces before you start dating." Such

prognoses were seen as a call to normalcy. The use of braces, crutches and wheelchairs,

that had made mobility possible and had been symbols of triumph over paralysis in the

hospital, became stigmata of "the crippled" and symbols of one's failure to have

recovered completely. Necessary assistive devices were quickly discarded, regardless of

the discomfort, fatigue, awkwardness or pain that resulted, as individuals strove for the

"appearance of complete physical normalcy" (21,27). Painful and exhausting physical

therapies were resumed upon patients' return home from hospital or initiated in those

who were not hospitalized. Physical therapy often continued for more than a decade

after the acute polio with the only goal being "complete recovery" (11). One patient,

who became triplegic at age six and has consistently thereafter used a wheelchair,

continued daily physical therapy until she left home for college, "Everyone believed that

physical therapy would make me walk - eventually." As motivation to walk without

braces, another patient was repeatedly beaten by his father who said, "I'd rather see you

dead than a cripple."

The abuse of polio survivors by parents was usually less overt but was not infrequent,

being motivated by a denial of polio and revulsion by disability (13,14,27). Some polio

survivors report being physically trapped by their parents' refusal to make

accommodations for their physical limitations. Homes frequently remained inaccessible,

making activities of daily living impossible without assistance from parents - assistance

that could be inconsistently provided or consistently withheld (28). One patient was

regularly carried outside in the early morning, regardless of the weather, where she

remained until dark. Another patient reported that he was locked in a car with windows

closed in the heat of midsummer so that his family could tour Washington's then

inaccessible national monuments. Polio survivors learned that physical abilities needed

to be maximized if they were to survive in a "barrier-full" society.

Other parents strove to reincorporate the child into the family routine and "forget" about

polio by requiring children to equal or exceed the level of physical performance they

exhibited before their illness (11). One patient's family took up hiking when their

daughter returned home from the hospital, expecting her to "learn to keep up with the

others" in spite of crutches and braces. Patients also report that they were expected to

out-perform their peers academically. Several patients reported that they would be

severely punished if they received "anything less than an "A"." Such academic

expectations reinforced the premature adult-like behaviors that were described in

children who had been hospitalized following the acute polio (22).

Still other parents experienced both "shame and estrangement" at having been "singled

out" by polio (22). Unable to deny the reality of their childs' disability, they isolated the

family from society and severely restricted their child's physical activities (11,14,22).

One patient, who had a barely noticeable limp following polio at 18 months, was

prevented from leaving his yard or playing with other children until he attended high

school. Such isolation impaired the development of social relationships (25,29,30) and

parental shame of disability was learned by the child (14). Unfortunately, many patients

report that their parents have consistently refused through the years to discuss anything

having to do with the physical or emotional reality of the polio experience (14,20). An

attempt at discussion with one 45-year old patient's mother was stopped by the angry

statement, "It's all too painful for me. Don't ever mention it again."

Whether unrealistically demanding or overly restrictive, parents' powerful expectations,

combined with those of physicians, nurses and therapists, dictated the behaviors that

were required of polio survivors if they were to escape "mortal danger" (15) and be

accepted by parents and society. Yet, despite the fulfillment of these expectations by the

achievement of a remarkable degree of functional recovery in most individuals and even

the appearance of "normalcy" in many, polio survivors were told that they were still not

acceptable (31). They report being told by teachers that no one would ever hire them, by

parents that no one would ever marry them, and by physicians that they should never

have children (28,32,33). Thus, as polio survivors entered adulthood they had

internalized the expectations of those in authority, which led to self-alienation and

actual participation in the "execution of the self" (24). Polio survivors continued to

follow the prescription for proper behavior set forth in the "Good Chart" even though

they had been told that fulfilling the expectations of others would not result in

acceptance by society (34).

Type A Behavior as a Post-Polio Sequelae

The majority of polio survivors have succeeded in minimizing the appearance of

disability, maximizing independence and "disappearing" into society (28). Most polio

survivors have learned to walk after discarding nearly all of their original assistive

devices (6). Despite society's negative expectations, polio survivors have had more

years of formal education and a larger proportion of them are married as compared to

the general disabled and non-disabled populations (Table 1)(35). Polio survivors also

have a higher level of employment as compared to the general disabled population (36).

These data suggested the hypothesis that polio survivors have not merely achieved

"normalcy" but have actually surpassed it by learning physically and emotionally

stressful Type A behavior as a response to their experience of polio (5,28,37). The polio

experience should have provided an ideal environment for the conditioning of Type A

behavior. Type A behaviors are thought to learned in service of the "active avoidance of

punishment" (38) by individuals who are engaged in a chronic "struggle to overcome

environmental barriers" (39) "against the opposing efforts of other things or persons"

(40). Further, Powell, et al (41) found that a "consistent set of beliefs and attitudes about

the self, others, and life in general lay beneath the overt (Type A) behavior," including

"low social support," "low self-esteem" and loss of control. Such beliefs would be the

likely consequence of the above-described experience of polio.

To test the hypothesis that polio survivors are Type A, the Brief Type A Questionnaire

(42) was administered to 738 polio survivors as part of the 1985 National Post-Polio

Survey (5). Polio survivors' mean Type A score of 53±22 was significantly higher than

that of non-disabled controls (36±14). This finding was replicated by the 1990 National

Survey of 373 polio survivors (6) who had a significantly elevated mean Type A score

of 59±22 as compared to non-disabled controls (45±20) and adults with spina bifida

(48±22)(Table 2).

Since it had been suggested that Type A individuals are hypersensitive to criticism (41),

the 1990 National Survey also included the Reinforcement Motivation Survey (RMS)

(43) that contains a Sensitivity to Criticism and Failure Scale. Polio survivors had a

significantly elevated mean Sensitivity to Criticism and Failure score (68±28) as

compared to non-disabled controls (59±27) that was significantly correlated with the

Type A score (r=0.44)(5). This correlation suggests that Type A behavior in polio

survivors serves in part to prevent criticism and to protect against feelings of failure

(21,44).

Compulsive Behavior as a Post-Polio Sequelae

The majority of patients treated by this Service not only demonstrate Type A behavior

but also evidence behaviors that are not typically Type A. Patients describe an inability

to express emotion or admit having physical pain ("I can't complain because people

expect the handicapped to complain"). They inflexibly and punitively judge their own

behavior on the basis of what is "normal" and on unachievable ideals of perfection. One

patient stated, "If I fail at anything, I might as well die. It boils down to either using

every ounce of my energy to lead a normal, successful life or giving in to my

weaknesses and being inferior."

Patients also demonstrate a strong need to be in control (15) and report marked anxiety

with and nearly phobic avoidance of any change ("I am constantly moving and in a

constant state of fear. I feel if I slow down, I'll never get started again") or decrease in

the number or extent of their activities ("I can't just sit and do nothing"). These patients

refuse to slow down, delegate responsibilities or allow others to assist them even when

they experience fatigue, weakness and pain. They report a saw-tooth pattern of activity,

characterized by working until physical symptoms prevent them from continuing.

Exhausted, anxious and fearful of criticism, they rest until activity is again possible and

then work until symptoms force them to halt. As one polio survivor stated, "I have spent

my whole life pushing to keep going and I still push myself even though I know I

shouldn't. I keep going until I can no longer walk or stand the pain. I cannot be stopped.

I work until I fall."

Patients also report that they "must" satisfy the real or perceived needs of others ("I can't

ever say 'No'") and some describe a compulsion to perform nearly ritualistic behaviors

in order to escape "mortal danger" (15). One patient stated, "I know it's ridiculous, but I

believe that if I make the bed every day I'll never die; I will earn the right to continue to

live."

These behaviors are reminiscent of the Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder

(OCPD)(45). However, polio survivors' compulsive behavior differs from OCPD in

important ways. Their compulsivity does not interfere with task completion or promote

indecisiveness, nor do polio survivors lack generosity in giving to others. On the

contrary, compulsive behaviors are goal-oriented and are performed in the service of

others. Importantly, these behaviors are associated with the exacerbation and

maintenance of PPS symptoms. Because of these differences with OCPD, a separate

diagnostic category, Compulsive Psychophysiological Disorder (CPD), is suggested to

highlight the relationship between goal-oriented, compulsive behaviors and the

occurrence of physical symptoms (Table 3).

Fifty percent of the patients evaluated by this service met the criteria for CPD. Further,

the diagnosis of CPD is significantly correlated with patients' elevated Type A (r=.46)

and Sensitivity to Criticism and Failure scores (r=.47) suggesting that compulsive

behaviors are related to Type A behavior and may also serve in part to prevent criticism

and to protect against feelings of failure. These findings support the theoretical literature

on compulsive behavior, which suggests that compulsivity protects against loss of

control and failure (46) and is used to "avoid or overcome distressful feelings of

helplessness" (47)(see "flashbacks," below). Millon and Everly (48) state that

compulsive behavior occurs when the "child never develops a separate identity, and

functions in the world by conforming to strict, internalized parental standards and to the

standards around him or her" - conditions that are described above as central to the

experience of polio. And, compulsive behavior has been seen to develop in children

hospitalized even for brief periods (20).

Compulsive, Type A Behavior and the Etiology of PPS

Unfortunately, polio survivors appear to have paid a high price for learning compulsive,

Type A behavior in an effort to achieve "normalcy," escape "mortal danger" (15) and

protect against the emotional pain generated by the polio experience. That price is Post-

Polio Sequelae (28). Physical overexertion and emotional stress were reported to be the

first and second leading causes of PPS on the 1985 National Survey (5). The majority of

respondents to the 1990 National Survey reported symptoms of chronic stress (frequent

feelings of anxiety, low mood and difficulty falling asleep because the "mind is

racing")(6,7,8). These symptoms, along with the Type A and Sensitivity to Criticism

and Failure scores, were significantly correlated with PPS symptom severity (Table

2)(5,6,49).

These data indicate that PPS are psychophysiological in nature and that clinicians must

address both physical and psychological symptoms when polio survivors present for

treatment of PPS. Thus, the treatment of PPS requires behavior modification to reduce

compulsive, Type A behavior and thereby decrease PPS symptoms. Psychotherapy is

also necessary to address the dysfunctional beliefs and powerful suppressed emotions

resulting from the experience of polio that motivate compulsive, Type A behavior,

produce psychological distress and prevent compliance with therapy.

Behavioral Modification and Psychotherapy in Treating PPS

All patients who present for treatment by the Post-Polio Service undergo complete

physiatric and psychological evaluations, the latter beginning with administration of the

Reinforcement Motivation Survey (RMS) (43) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

(50). Of the 32 patients evaluated during the past year, the majority had elevated Type

A (mean = 57 ± 28 ) and Sensitivity to Criticism and Failure (mean = 75 ± 28) scores on

the RMS but had insignificantly elevated BDI scores (mean = 14 ± 9).

Although 57% of patients reported "low mood," only 31% met DSM-IIIR criteria for

Major Depressive Episode (MDE), a percentage similar to the 32% reported by

Freidenberg, et al. (51) but higher than the prevalence of MDE in the general population

(3% to 7%) (52,53) and in those with medical illness (20%) (54). Friedenberg, et al.

(51) suggested that damage to monoaminergic neurons in the brain stem may predispose

polio survivors to MDE (see 49). However, the report of "treated depressions" in 38%

of adults with spina bifida suggests that childhood-onset orthopedic disability itself may

predispose to MDE in adults (55).

The presence of MDE in our patients is important, not only because it requires

treatment, but also because MDE is significantly correlated with treatment non-

compliance. MDE was diagnosed in 63% of patients who refused further treatment after

the initial evaluation and in 50% of those who were discharged for therapeutic non-

compliance. Only 11% of patients who were fully compliant and 29% of those who

were partially compliant with therapy were diagnosed as having a MDE. MDE is

always treated with psychotherapy, although depression was sufficiently severe in 70%

of patients that an antidepressant was recommended.

Following psychometric testing, psychological, medical and psycho social histories are

taken that include detailed descriptions of the new symptoms and their causes, the acute

polio experience, post-polio rehabilitation and patients' personal experience of

disability. Information about the response of family, friends and community to the acute

polio, to patients' original disability and to PPS is elicited along with a chronology of

school and vocational achievements noting the onset and development of compulsive,

Type A behavior.

Treatment. The treatment of PPS is approached by all members of the treatment team -

physician, psychologist and occupational and physical therapists - from a

psychophysiological perspective using the techniques of multimodal behavior therapy

(56). Therapy begins by asking patients to list their treatment goals and keep a daily log

of activities, perceived exertion, fatigue, muscle weakness, pain, emotional stress,

thoughts and emotions. This log is used to document physical and emotional symptoms

and demonstrate their relationship to thoughts, affect and compulsive, Type A behavior

(56). Outpatients are then evaluated by occupational and physical therapists during

twice-weekly sessions. Inpatients receive all therapies daily. After two weeks, log data

and evaluation results are used by the treatment team to formulate a behavioral plan

designed to decrease behaviors that cause physical symptoms, initiate self-care activities

and incorporate stress and time management, energy conservation, work simplification

and a program of relaxation, stretching and non-fatiguing progressive resistance

exercises (57) into patients' daily routine. The behavioral plan is then presented to

patients and their significant others at a meeting with the treatment team. Also discussed

are the hypothesized causes of PPS, the need to modify behavior to treat PPS and the

team's expectation of total compliance with all aspects of the behavioral plan. Patients

continue to keep logs throughout their treatment to document symptoms, the

progression of exercises and modification of behaviors. Logs are reviewed with patients

by each therapist at every treatment session. Goals are reviewed by the entire treatment

team at twice-monthly behavioral rounds. Problems with the behavioral plan, especially

those having to do with compliance, are communicated immediately to all members of

the team. Significant problems with compliance may require that patients be called in to

meet with the team. If no significant problems develop, patients meet with the team

once again at the end of the eight to twelve week treatment program.

Compliance problems often arise with the daily log and the behavioral plan. Patients

have difficulty keeping the log because it interferes with the compulsive performance of

their scheduled activities and forces them to recognize the severity and pervasiveness of

their symptoms. Invariably, patients have difficulty in complying with the behavioral

plan. They will 'forget' to alter their schedules and refuse lifestyle modification because

such changes directly conflict with their compulsive, Type A behavior (46). As one

patient who was discharged for non-complince angrily stated, "I don't want to change. I

just want to be the way I was."

Unfortunately, such problems with compliance are typical of post-polio patients. One

clinic reported that only 41% of patients sporadically used a newly prescribed brace

while 70% refused to use a new cane or crutch simply because they "didn't want to"

(58). Another clinic concluded that "the major reason for failure (of PPS symptoms) to

improve was the unwillingness of the patient to follow any of the recommendations

made" (59). Peach (60) has documented the importance of compliance with regard to

the treatment of PPS muscle weakness, showing that muscle strength decreases over

time only in patients who fail to fully comply with therapeutic recommendations.

During the past year, 47% of the patients treated by this service were judged to be fully

compliant, 34% only partially compliant while 19% were discharged from therapy for

not complying with the behavioral plan . Of all patients who received an initial

evaluation, 28% refused any treatment for their PPS. It appears that inadequate

compliance results in part from patients' fear of relinquishing compulsive, Type A

behavior that is believed by them to protect against "mortal danger" (15). Some non-

compliant patients fear that PPS will return them to the same position of helplessness

that they experienced following acute polio (cf. 47). Most report an even greater fear of

criticism and a sense of failure when they merely contemplate lifestyle changes or the

use of new assistive devices, even though without them PPS symptoms persist, progress

and functional ability deteriorates. Not unexpectedly, inadequately compliant patients

have an elevated mean Sensitivity to Criticism and Failure score (81 ± 2 0) as compared

to fully compliant patients (74 ± 35).

Patients' ability to change their behavior is directly related to their ability to challenge

long-held beliefs about self-worth and survival and tolerate the emergence of the

powerful fears and long-suppressed emotions generated by the polio experience (41). To

promote compliance with the behavioral plan, cognitive therapy techniques are

employed through weekly individual psychotherapy to identify and modify

dysfunctional beliefs, fears and emotions (46). Learning theory is also employed to

explain how compulsive, Type A behavior was learned to protect against fear,

emotional pain and "mortal danger" (15), while behavior modification techniques are

used to decrease and eliminate these overlearned behaviors (41,46).

As these techniques assist patients to decrease compulsive, Type A behavior, increased

anxiety and fear invariably result. Some patients report insomnia, panic attacks,

intrusive and emotionally-charged flashbacks about their early polio experience and

even fear of impending death (47). The psychotherapist then helps patients understand

the origin of these most disturbing experiences and learn to tolerate them, reinforces the

new self-care behaviors and supports patients through what can be terrifying days and

nights.

As therapy continues, patients discover that their compulsive, Type A behavior has been

more habitual than necessary. They begin to discard the "Good List," become better

able to care for themselves and begin to believe that they can have both self-worth and a

disability. As the behaviors and emotions conditioned by the polio experience decrease,

the focus of psychotherapy shifts to the experience of PPS. Depressed mood is replaced

by sadness and anger as the trauma of a "second disability" is experienced (4). Twice-

monthly group psychotherapy provides peer support to assist patients in dealing

emotionally with their PPS and practically with the lifestyle changes necessary to treat

them. The realization by patients in the group that they are not alone in their painful

physical and emotional experiences is itself powerfully therapeutic. Couples and family

sessions are also employed for both education about PPS and psychotherapy. It is

noteworthy that nearly all spouses, with some striking exceptions, respond favorably to

patients' lifestyle changes with the most frequently heard comment being, "I've been

wanting you to slow down for years."

All patients treated by this Service, whether fully or even partially compliant, report

meaningful reductions in physical and affective symptoms and increased function (cf.

60). But, as fatigue, muscle weakness and pain decrease, patients frequently increase

activity and have a tendency to resume compulsive, Type A behavior (46). To prevent

this, patients are instructed to strictly adhere to the modified daily schedule as set forth

in their behavioral plan, especially after they are discharged from physical and

occupational therapies and individual psychotherapy. Patients continue in group

psychotherapy for at least six months after discharge, are seen at three-month intervals

for medical and psychological follow-up and are encouraged to call their therapists at

any time with questions or for support.

Conclusion

It is possible that the large proportion of patients treated by this Service who have

experienced severe psychological trauma as a result of their polio experience may not

be representative of all polio survivors or even of all individuals who present for

treatment of PPS. However, there is something unique about the experience of polio that

predisposes to the development of compulsive, Type A behavior, sensitivity to criticism

and failure and chronic stress, anxiety and depression: the early onset of a universally

feared, potentially life-threatening illness that presented in epidemic proportions; the

experience of severe paralysis that could be forced to recede with the application of

years of strenuous physical therapy; the need to maximize physical abilities in order to

function in a "barrier-full" society that was repelled by disability; the sparing of

intellectual abilities that were used to overcompensate for residual physical limitations

(61,62). These factors must be studied if we are to understand the psychology of the

polio survivor, maximize treatment compliance and effectively treat both the physical

and psychological symptoms of PPS.

TABLES

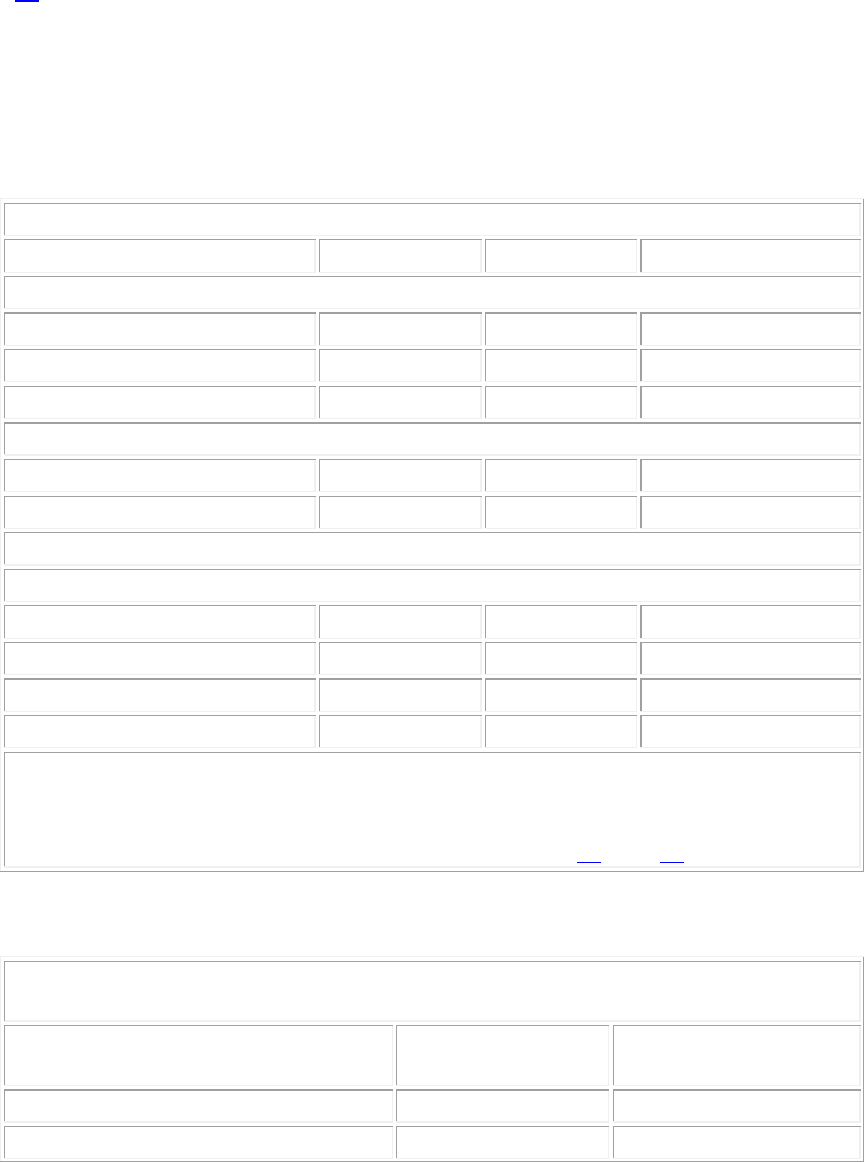

Table 1 [below]

EDUCATIONAL, MARITAL, AND EMPLOYMENT STATUS*

Post-Polio

Disabled

Non-Disabled

Marital Status

Single

11%

13%§

22%§

Married

71%

56%

58%

Other¤

18%

31%

20%

Education

< High school

29%

71%§

52%§

> High school

71%

29%

48%

Employment Status

Working

All positions¥

53%

38%§

79%**

Full time

40%

24%

59%

Unemployed

3%

62%

6%

Disability payments

28%

36%

1%

* Respondents to the 1990 National Post-Polio Survey compared with disabled and non-

disabled Americans.

¤ Divorced, widowed, or separated.

¥ Full-time, part-time, or homemaker. Data from reference 35§ and 36**.

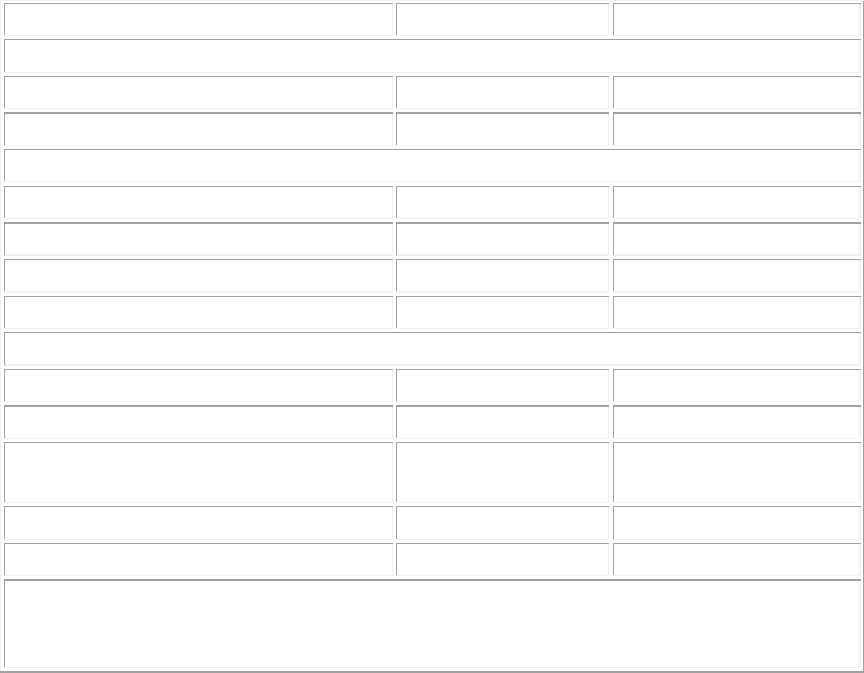

Table 2 [below]

DEMOGRAPHIC DATA, NEW SYMPTOMS, AND PSYCHOLOGICAL

MEASURES*

Post-Polio Subjects

(n = 373)

Non-Disabled Controls

(n = 145)

Age

54 ( ±11 )¤

47 ( ± 14)

Female/Male ratio

1.5

1.5

Years of education

14.5 ( ± 3)

15 ( ± 3)

Reinforcement Motivation Survey Scores:

Type A

59 ( ± 22)¤

45 ( ± 20)

Sensitivity to Criticism and Failure

68 ( ± 28)¤

59 ( ± 27)

New Symptoms

Fatigue

83%¥

15%

Muscle weakness

75%¥

9%

Pain

72%¥

15%

Emotional stress increases symptoms

75%¥

53%

Psychological Symptoms

Frequent feelings of anxiety

69%¥

36%

Chronic back/neck pain

66%¥

35%

Frequent trouble falling asleep

because "mind is racing"

65%¥

33%

Frequent "low mood"

57%§

41%

Diagnosed depression

27%§

15%

* From the 1990 National Post-Polio Survey

Significantly different from control values using independent groups t-test (¤P<.001) or

chi-square statistics (§P<.002; ¥P<.0001).

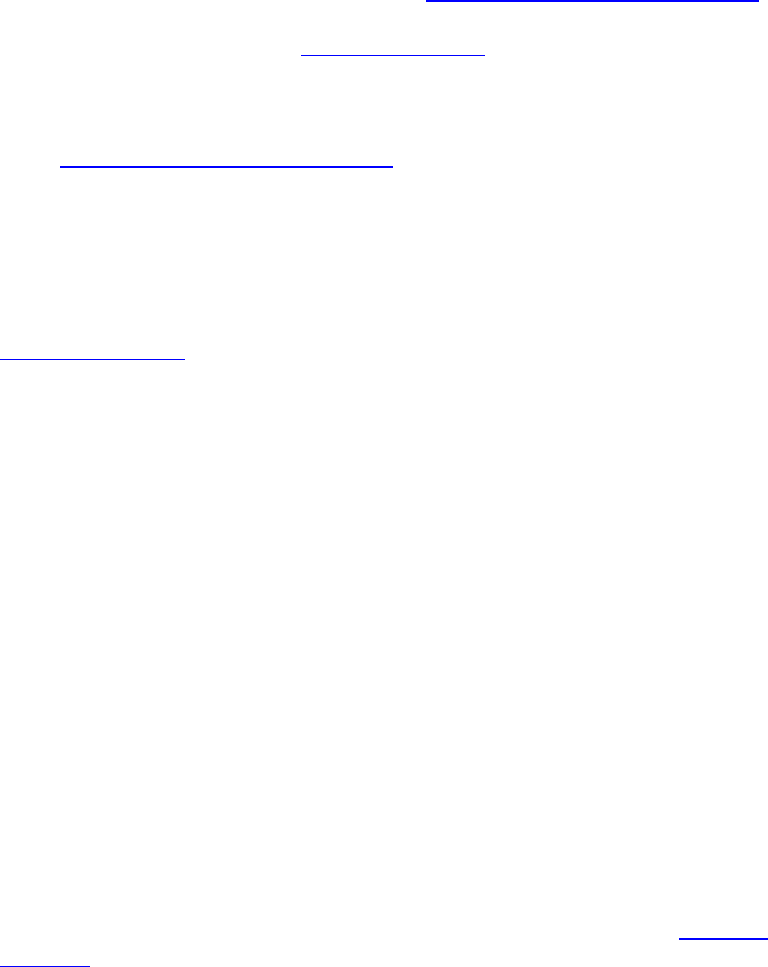

Table 3 [below]

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR COMPULSIVE PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGICAL

DISORDER

A.

A pervasive pattern of continuous and excessive goal-oriented behaviour beginning

in childhood or adolescence as indicated by at least four of the following:

1.

Marked anxiety generated by and avoidance of any decrease in goal-oriented

activities or changes in daily schedule

2.

Refusal to delegate responsibilities or allow others to provide assistance

associated with an unusually strong need to be in control

3.

Rigidly and inflexibly judges behaviour on the basis of ideals of perfection or

"normality"

4.

Excessive time-consciousness and Type A behaviour

5.

Extreme sensitivity to criticism with the constant expectation of failure and

rejection

6.

Inability to identify or express emotion, with the exception of anxiety, anger, and

sadness.

B.

The association of these behaviours with the exacerbation or maintenance of physical

symptoms, such as muscle spasm-induced pain, fatigue, or muscle weakness.

REFERENCES

1. Gallagher HG: FDR's Splendid Deception. New York, Dodd, Mead, 1985.

2. Parsons PE: Data on polio survivors from the National Health Interview Survey.

Washington, D.C., National Center for Health Statistics, 1989.

3. Frick NM: Post-Polio Sequelae: Physiological and Psychological Overview.

Rehabilitation Literature 1986: 47:106-111. [Lincolnshire Library Full Text]

4. Frick NM: Post-Polio Sequelae and the psychology of second disability.

Orthopedics 1985; 8: 851-853. [PubMed Abstract]

5. Bruno RL, Frick NM: Stress and "Type A" behavior as precipitants of Post-

Polio Sequelae, in Halstead LS and Wiechers DO (eds): Research and CLinical

Aspects of the Late Effects of Poliomyelitis. White Plains, March of Dimes,

1987. [Lincolnshire Library Full Text]

6. Bruno RL, Frick NM: Psychological profile of polio survivors. Arch Phys Med

Rehabil 1990; 10: 889.

7. Bruno RL, Frick NM: Five year follow-up to the 1985 National Post-Polio

Survey. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1990; 10: 886.

8. Conrady LJ, Wish JR, Agre JC, Rodriquez, AA, Sperling, KB: Psychological

characteristics of polio survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1989; 70: 458-463.

[PubMed Abstract]

9. Bozarth CH: Unfinished Business: Support Group Members Confront Feelings

Surrounding the Late Effects of Polio. Lansing, Polio Survivors Support Group,

1987.

10. Copellman FS: Follow-up of one hundred children with poliomyelitis. The

Family 1944; December: 189-196.

11. Meyer E: Psychological considerations in a group of children with

poliomyelitis. J Pediatrics 1947; 31: 34-48.

12. Moustakas CE: Loneliness. Englewood Cliffs, Prentice Hall, 1961.

13. Seidenfeld MA: The psychological sequelae of poliomyelitis in children. The

Nervous Child 1948; 7: 14-28.

14. Wright BA: Physical Disability - A psychosocial approach. New York, Harper

and Row, 1983.

15. Register C: Living with Chronic Illness. New York, Free Press, 1987.

16. Berg RH: Polio and its Problems. Philadelphia, Lippincott, 1948.

17. Billig HE, van Harreveld A, Wiersma CAG: On re-innervation of paretic

muscles by the use of their residual nerve supply. J Neuropath Exp Neurol 1946;

5:1-23.

18. Kerr N: Staff expectations for disabled persons. Rehabilitation Counseling

Bulletin 1970; 14: 85-94.

19. Hawke WA, Auerbach A: Multidiscipline experience: A fresh approach to aid

the multihandicapped child. Journal of Rehabilitation 1975: 41:22-24. [PubMed

Abstract]

20. Rowlands P: Children Apart. New York, Pantheon, 1973.

21. Schechter MD: The orthopedically handicapped child. Arch Gen Psychiatry

1961; 4: 53-59.

22. Davis F: Passage Through Crisis. Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill,1963.

23. Rice EP: The families of children with poliomyelitis, in Poliomyelitis.

Philadelphia, Lippincott, 1949.

24. Moustakas CE: Loneliness and Love. Englewood Cliffs, Prentice Hall, 1972.

25. Ladieu-Leviton G, Adler DL, Dembo T: Studies in adjustment to visible

injuries: Social acceptance of the injured. Journal of Social Issues 1948; 4: 55-

62.

26. Davis F: Illness, Interaction and the Self. Belmont, California, Wadsworth,

1972.

27. Long L, Roth C: The psychological aspects of rehabilitation, in Soden WH (ed)

Rehabilitation of the Handicapped. New York, Ronald, 1949.

28. Trieschmann RB: Aging with a Disability. New York, Demos, 1987.

29. Battle CU: Disruptions in the socialization of a young, severely handicapped

child. Rehabilitation Literature 1974; 35:130-140. [PubMed Abstract]

30. Anthony WA: Societal rehabilitation: Changing society's attitudes toward the

physically and mentally disabled. Rehabilitation Psychology 1972; 19: 117-126.

31. Wright BA: Issues in overcoming emotional barriers to adjustment in the

handicapped. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 1967; 11: 53-59.

32. Bloom JL: Sex education for the physically handicapped. Sexology 1970; 36:

62-65.

33. Hohmann GW: Reactions of the individual with a disability complicated by a

sexual problem. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1975; 56: 8-13. [PubMed Abstract]

34. Ladieu G, Hanfmann E, Dembo T: Studies in adjustment to visible disability.

The Journal of Abnormal Social Psychology 1947; 42: 169-192.

35. Taylor H, Kagay MR, Leichenko S: The ICD Survey of Disabled Americans.

New York, Louis Harris, 1986.

36. Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1990 (110th edition). U.S. Bureau of

the Census, Washington, D.C., 1990.

37. Bruno RL, Frick NM: The origins of "Type A" behavior and stress induced

symptoms in polio survivors. Proceedings of the Society of Behavioral Medicine

1989; 10: 85.

38. Perkins KA: Heart rate change in Type A and Type B males as a function of

response cost and task difficulty. Psychophysiology 1984; 21: 14-21. [PubMed

Abstract]

39. Rosenman RH, Friedman M, Straus R, et al: A predictive study of coronary

heart disease. JAMA 1964; 189: 113-124.

40. Friedman M, Thoresen CE, Gill JJ, et al: Feasibility of altering Type A behavior

pattern. Circulation 1982; 66: 83-92. [PubMed Abstract]

41. Powell LH, Friedman M, Thoresen CE, et al: Can the Type A behavior pattern

be altered after myocardial infarction? Psychosom Med 1984; 46: 293-313.

[PubMed Abstract]

42. Young LD, Barboriak JJ: Reliability of a brief scale for assessment of coronary-

prone behavior and standard measures of Type A behavior. Percept Mot Skills

1982; 55: 1039-1042. [PubMed Abstract]

43. Bruno RL: Predicting pain management program outcome: The Reinforcement

Motivation Survey. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1990; 10: 785.

44. Mandell AJ: Toward a psychobiology of transcendence, in Davidson JM,

Davidson RJ (eds): The Psychobiology of Consciousness, New York, Plenum, 1

980.

45. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (ed 3, revised).

Washington, D.C., American Psychiatric Association, 1987.

46. Beck AT, Freeman A: Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders. New York,

Guilford, 1990.

47. Salzman L: The Obsessive Personality. New York, Jason Aronson, 1973.

48. Millon T, Everly G: Personality and its Disorders. New York, Wiley, 1985.

49. Bruno RL, Frick NM, Cohen J. Polioencephalitis, stress and the etiology of

Post-Polio Sequelae. Orthopedics 1991; (this issue). [Lincolnshire Library

Full Text]

50. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al: An inventory for measuring

depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4: 561-571.

51. Freidenberg DL, Freeman D, Huber SJ, Perry, J, Fischer, A, Van Gorp, W G, et

al: Postpoliomyelitis Syndrome: Behavioral Features. Neuropsychiatry,

Neuropsychology and Behavioral Neurology 1989; 2: 272-281. [Lincolnshire

Library Full Text]

52. Myers JK, Weissman MM, Tischler OL, et al: Six month prevalence of

psychiatric disorders in three communities. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41: 959-

967. [PubMed Abstract]

53. Roberts RE, Vernon SW: Depression in the community: Prevalence and

treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39: 1407-1409. [PubMed Abstract]

54. Schleifer SJ, Macari M, Slater W, et al: Predictors of outcome after myocardial

infarction: Role of depression. Circulation 1987; 74 (supplement II): 38.

55. Dunne KB, Gingher N, Olsen L, et al: The Adult Spina Bifida Network Survey.

Insights 1986; 14: 28-32.

56. Lazarus A: Multimodal Behavior Therapy. New York, Springer Verlag, 1976.

57. Fillyaw, et al. Orthopedics December, 1991.

58. Waring WP, Maynard F, Grady W et al: Influence of appropirate lower

extremity orthotic management on ambulation, pain and fatigue in a postpolio

population. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1989; 70: 371-375. [PubMed Abstract]

59. Agre JC, Rodriquez AA, Sperling KB: Symptoms and clinical impressions of

patients seen in a postpolio clinic. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1989; 70: 367-370.

[PubMed Abstract]

60. Peach PE, Olejnik S: Effects of treatment and noncompliance on post-polio

sequelae symptoms and muscle strength. Orthopedics 1991; (this issue).

[Lincolnshire Library Full Text]

61. Scheer J, Luborsky M: Culture and polio. Orthopedics 1991; (this issue).

[PubMed Abstract]

62. Not present in source document.