e UK’s wealth distribution

and characteristics of high-

wealth households

Arun Advani, George Bangham & Jack Leslie

December

@resfoundationresolutionfoundation.org

BRIEFING

Download

This document is available to download as a free PDF at:

https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/

Citation

If you are using this document in your own writing, our preferred citation is:

A Advani, G Bangham & J Leslie,

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households: Reports are fun,

Resolution Foundation, December 2020

Permission to share

This document is published under the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial No

Derivatives 3.0 England and Wales Licence. This allows anyone to download, reuse, reprint,

distribute, and/or copy Resolution Foundation publications without written permission subject to

the conditions set out in the Creative Commons Licence.

For commercial use, please contact: info@resolutionfoundation.org

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council

(ESRC) through the CAGE at Warwick (ES/L011719/1) and a COVID-19 Rapid

Response Grant (ES/V012657/1), by LSE International Inequalities Institute

AFSEE COVID-19 fund, and by the Standard Life Foundation. The authors

thank Hannah Tarrant and Helen Hughson for outstanding research

assistance, and Emma Chamberlain, Carla Kidd, Salvatore Morelli, and Andy

Summers for helpful comments. This work contains statistical data from ONS

which is Crown Copyright. The use of the ONS statistical data in this work

does not imply the endorsement of the ONS in relation to the interpretation

or analysis of the statistical data. This work uses research datasets which may

not exactly reproduce National Statistics aggregates. All errors remain the

author’s own.

2

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

3

Introduction

In high-income Western economies during much of the twentieth century, economic

questions of distribution – of income or other variables – seemed of secondary

importance to those of macroeconomic growth. This focus for research was more

understandable in an era of economic expansion, broadly rising living standards and

falling inequality. But in the past 40 years trends of falling inequality have faltered or even

reversed. More recently, trends in growth and productivity have slowed down too. With a

lag, economists’ interests have followed suit: high-profile research on income distribution

paved the way for a more recent wider focus on other types of inequality such as that of

wealth, particularly since the publication of Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Piketty,

2014). This research has led policymakers to think more about the distribution and

growth of wealth, as well as options for taxing it.

This paper sets the scene for the broader project by examining the distribution of wealth

in the UK today.

1

It considers the three types of data that are available to researchers

looking at the wealth distribution – household surveys, administrative data from income

and inheritance tax, and lists of large wealth-holders – and then looks at what the first of

these can tell us about the ownership of wealth. It also discusses the limitations of the

different methods for studying the amount and distribution of wealth, and demonstrates

with a Pareto distribution-based extension of the available data that true levels of wealth

(and of wealth inequality) are likely to be higher than those shown in the conventional

statistics.

A detailed understanding of the distribution of wealth matters when designing wealth

taxes in at least three distinct ways. First, it helps policymakers to gauge the likely welfare

impact of changes to the tax regime for wealth and particularly what the characteristics

of people affected would be with respect to present income, age, location and other

key variables. Second, the distribution of wealth is itself a key determinant of people’s

living standards, at least as much as the more often-studied income. Holding wealth

not only permits people to smooth their consumption and insure against risk, but also

confers direct benefits for personal wellbeing and life chances (and those of someone’s

descendants): the so-called ‘asset effect’ (McKnight and Karagiannaki, 2013). Third,

1 Though we refer to the UK throughout this paper, our data exclude Northern Ireland, Northern Scotland (north of the Caledonian

canal), and individuals living in residential institutions such as prisons, university accommodation, and care homes. As a result,

we miss around 2% of the UK population. Unless these areas are drastically different from the rest of the UK, it is unlikely that

our distributional results are substantially affected. In principle, if the distribution of wealth in these areas is identical to what we

observe elsewhere, we could increase our aggregate measures of wealth by 2%, but given the inherent uncertainty involved in

using survey data, we do not take this approach, and we do not expect it to change our results substantially. We do include some

of the wealthiest individuals in the areas omitted from the survey data, as these individuals are captured in the Sunday Times Rich

List which we use to supplement our estimates.

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

4

the combination of tax structure and wealth distribution (along with any behavioural

responses to the tax) determine how much revenue will be raised.

Distributional analysis of wealth ownership demands a dataset that measures both

wealth and other personal characteristics. At present, the ONS Wealth and Assets Survey

is the only such comprehensive dataset available for Great Britain,

2

so it forms the core of

our analysis. We find that the top three household net wealth deciles held a larger share

of wealth in 2016–18 than ten years earlier, and the middle 50% shrank. This has been

driven by rising financial wealth relative to property wealth. Importantly, average gains in

financial wealth over the past decade are explained more by passive capital gains than

by active saving,

3

and wealth gains have accrued mostly to families that already held

financial assets. We find that a major driver of rising inequality is that wealthy families’

financial portfolios will contain a greater share of high-yielding assets (consistent with

Bach, Calvet and Sodini, 2020; Fagereng et al., 2020), and show that population ageing

alone does not explain very much of the recent change in the distribution of wealth.

Lower wealth households (the second and third net wealth decile) have a larger share of

wealth in physical assets (largely consumer durables) than in other broad asset classes,

while wealth for the fifth to eighth deciles is dominated by property, and for the top

two deciles dominated by pensions. Financial wealth is much more prevalent in the

wealthiest decile, and its composition varies substantially across net wealth deciles,

though even the wealthiest families have a significant share in low-yielding assets.

We also consider the characteristics of high-wealth households who would likely be

impacted by the introduction of a wealth tax, and the types of wealth they hold. They

are clustered in working-age cohorts close to retirement, and are more likely to be male

than female. There are large geographical divides, with high-wealth families much more

concentrated in the South East of England than in the rest of Great Britain. There is also

low volatility in wealth rank: only 7% of families in the bottom half of the distribution in

2014–16 moved into the top half two years later. Finally, the composition of high-wealth

families’ wealth holdings is much more dominated by business and financial assets (and

relatively less by property and pensions) for those families with net wealth over £5 million

per adult than for families with lower wealth levels.

A well-known problem with household surveys is that it can be difficult to capture

a complete representative sample of all individuals. We explore this problem, with a

particular focus on the very wealthiest families in the UK, using the Sunday Times Rich

List. Our analysis finds that the ONS’s Wealth and Assets Survey does a remarkably good

2 Unfortunately, there is no comprehensive survey of wealth in Northern Ireland comparable to the ONS Wealth and Assets Survey,

though Hillyard, Patsios and Feely (2014) do provide some evidence on wealth held in Northern Ireland to which the interested

reader may refer.

3 See Corlett, Advani and Summers (2020) for more information on capital gains.

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

5

job at capturing some of the wealthiest people in the UK but that there is likely to be at

least some undercount in official estimates of total wealth. Further, we find evidence

from fitting a Pareto distribution to UK wealth data (often found to be a good fit of the

upper wealth tail of the wealth distribution in a range of contexts) that both the Wealth

and Assets Survey and the Sunday Times Rich List underestimate family wealth at the

very top of the distribution. Adjusting for these deficiencies by adding in wealth captured

in the Rich List that is not captured in the Wealth and Assets Survey, and subsequently

accounting for additional missing wealth using a Pareto adjustment, increases survey

estimates of total wealth by 5% in our central estimate, adding almost £800 billion in

wealth. Around half of this comes from simply adding wealth captured in the Rich List

that is not recorded in the Wealth and Assets Survey.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 details the available data in the UK

on household wealth, and the approach we have taken to analyse it. Section 3 describes

the size and distribution of household wealth in the UK. Section 4 analyses the gaps

in the available data, and the impact on estimates of the wealth distribution after

accounting for deficiencies in data coverage. The conclusion summarises our findings

and their implications for the rest of the project.

Data and methodology

The primary challenge in understanding the scale and distribution of wealth in the UK

is the data available for research. Broadly speaking, there are three key types of data:

first, survey-based data collecting households’ self-reported wealth holdings – key here

is the Office for National Statistics’ (ONS) Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS); second,

administrative data collected for tax purposes, one example is the data on the value of

estates at death for inheritance tax; and finally, data compiled for other purposes such as

the Sunday Times Rich List (STRL). Each of the datasets entails significant challenges in

allowing us to produce comprehensive estimates of the distribution of wealth in the UK

(for a wider discussion see Alvaredo, Atkinson and Morelli, 2016).

Survey data

The WAS provides the most comprehensive wealth data available in the UK, both in

terms of who it covers and what assets are covered. It has been conducted since 2006

with the purpose of capturing very granular information on the value of household

wealth – both assets and liabilities – at the individual and household level. The ONS

produces summary statistics and allows researchers access to anonymised microdata.

4

This allows us to produce detailed analysis by asset and liability type broken down by key

characteristics of the individual or household.

4 See, for example, ONS (2020).

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

6

The WAS samples private households with an address in Great Britain. In principle, this

means the survey could capture those who only live in Great Britain part-time who are

not strictly ‘resident’, though in practice it is unlikely that many such individuals respond

to the survey. Individuals who are resident but non-citizen are also within the scope of

the survey.

5

The survey is unlikely to fully capture the wealth of families where one family

member lives outside the UK, as this individual would not be interviewed or classified

as a member of the household, and their wealth (unless owned jointly with an eligible

household member) would not be captured. The sample excludes individuals living in

residential institutions, such as retirement homes, nursing homes, prisons, barracks

or university halls of residence, and homeless people. We therefore do not observe the

wealth of these individuals, who number approximately 1.2 million (Corlett et al., 2018).

There are three major challenges that face researchers using the WAS. First, the time

series is relatively short which does not allow the data to be placed within its long-run

historical context. Second, it is hard to value some types of assets (largely non-financial

assets) which do not have a clear market price; the survey is designed to rely on the self-

reported subjective value of these assets which may introduce biased valuations.

6

Third,

and perhaps most importantly for this paper, some wealth is unlikely to be captured by

the WAS. This is due to unit non-response where richer households are less likely to

respond to the survey,

7

item non-response where survey respondents fail to include their

assets, particularly business assets, and indirect holding of wealth through trusts and

other vehicles, particularly at the very top of the distribution. Despite these challenges,

the WAS remains the best source of data on the wealth holdings across much of the UK’s

wealth distribution; indeed, since its inception, the survey has formed the bedrock of

much of the recent analysis of wealth in the UK, for example, Crawford, Innes and O’Dea

(2016) and D’Arcy and Gardiner (2017).

Administrative data

For analysing changes to existing taxes, administrative data has the clear advantage of

covering the full population of those paying the tax. But the UK does not have an existing

comprehensive wealth tax meaning that there is no complete administrative dataset on

wealth holdings in the UK. Inheritance tax data are available for taxable wealth held at

death by people whose estates require probate.

8

Capital income taxes (taxes on income

from wealth) mean administrative data also cover wealth which produces taxable income,

5 We discuss data issues relating to residency and citizenship further in Section 4.3.

6 Appleyard and Rowlingson (2010) note that there is some evidence of overestimating the value of housing in early waves of the

WAS, and the same appears to be true in later waves (ONS, 2018). We discuss this issue further in Section 4.3).

7 The ONS attempt to account for lower response rates among wealthier households by over-sampling households identified ex

ante as likely to be in the wealthiest tenth of households.

8 Despite the name, inheritance tax (IHT) data cover all estates requiring probate, regardless of whether any IHT is due on the estate.

This means that they cover estates valued below the exemption threshold for IHT (currently £325,000), if probate is required on at

least one of the assets making up the estate.

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

7

from which it is possible to estimate the value of the underlying asset,

9

but assets which

don’t generate income will be missed, such as owner-occupied homes. While consistency

of definition and legal requirements to report ensure that administrative data are of good

quality for individuals who are required to report, not all individuals, and not all assets, will

be covered: for example, relatively few estates pay inheritance tax. However, tax planning

may also affect the extent to which reported wealth captured accurately reflects the

wealth of the living population. For example, most lifetime gifts of cash do not need to

be reported however substantial, unless the donor dies within seven years, and such

transfers of wealth do not have to be shown on any probate forms or on the recipient’s

tax return.

Some of these administrative data have been used to analyse the top of the UK’s wealth

distribution in previous research – specifically inheritance tax data. Alvaredo, Atkinson

and Morelli (2018) estimate the share of wealth at the top of the distribution since the

nineteenth century, using ‘mortality multipliers’ that treat the deceased as a sample of

the living population. This approach is valuable as it would theoretically capture all high-

wealth estates and thus is not subject to the high-wealth unit non-response present

in the WAS. However, though inheritance tax data capture 100% of estates with an

inheritance tax liability, it may fail to capture the wealth held in estates valued above the

exemption threshold (currently £325,000 per person) if no inheritance tax is due, even

if probate is required. This is because non-taxpaying estates, such as those where the

deceased is resident but non-domiciled,

10

or estates claiming exemptions and reliefs,

11

are not necessarily required to report all assets. A further concern is that the wealth

observed on death is not representative of the wealth of the living as individuals nearing

death may engage in ‘deathbed planning’.

But the major drawback, in so far as we would want to study the whole wealth

distribution, is that inheritance tax data fail to capture key parts of it. Inheritance tax data

only cover estates requiring probate, which is roughly half of all estates passing on death

(HMRC, 2019, p.4). Many smaller estates do not require probate, nor do estates which are

jointly held and pass automatically to the surviving spouse (potentially including some

high-value estates). There are no hard rules determining whether probate is required,

and it is difficult establish how probate incidence, and thus inclusion in the data, varies

across the wealth distribution. Estates data also do not cover all asset classes, with

9 This approach estimates the level of wealth across the distribution by applying asset return rates to more readily observed capital

income. However, it is very sensitive to assumptions about the rate of return, with small differences in return rate assumptions

leading to large changes in estimated wealth – see Smith, Zidar and Zwick (2020), and Saez and Zucman (2020a, 2020b).

10 If the deceased is non-domiciled, inheritance tax is only due on assets located in the UK, and they are not obliged to report the

total value of worldwide assets. Conversely, the data include the estates of individuals who are domiciled but are not resident in

the UK, as these are chargeable to IHT.

11 Some assets classes receive full tax relief (such as agricultural and business property); while data is available for these assets, they

may not properly reflect true values because the tax authority has no incentive to check submissions given their exclusion from

tax liability.

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

8

pension assets and some assets held in trust being excluded. This means that the data

are insufficient for the purpose of this paper to summarise the entire wealth distribution.

Adjusting top wealth

The approach taken in this paper is to rely on the WAS as the basis for the primary

analysis – see Section 3 – as it is the most comprehensive and detailed summary of

household wealth. Following these results, we provide analysis of the scale of any

missing wealth not covered by the WAS and indicative results after adjusting for these

gaps – see Section 4.

In order to calculate the amount of wealth at the top of the wealth distribution which is

not captured by the WAS, we utilise the STRL which provides summaries of the wealth

held by the wealthiest individuals and families in the UK. Unfortunately, these two

datasets are not completely comparable; this is unsurprising given that the STRL data is

produced primarily from holdings of business assets and does not include other asset

types, such as housing (Watts, 2020). Therefore the STRL is best thought of as a lower

bound on the wealth levels of the very wealthiest families in the UK.

12

Combining the STRL and the WAS will capture more of the wealth distribution than either

does alone but it is possible that there will be wealth holdings which are not properly

captured by either dataset. In order to estimate this potential gap, we utilise an approach

taken by Vermeulen (2018) and Bach, Thiemann and Zucco (2019). This approach

assumes that the top tail of the wealth distribution matches a Pareto distribution, which

is commonly found to be the case for both the wealth and income distributions (Jones,

2015). The Pareto distribution is estimated using the combined WAS and STRL sample.

The total estimated wealth under the full Pareto distribution is then compared to the

survey data – if the data is found to underestimate total wealth relative to the Pareto

distribution, then that represents the missing wealth not captured by either survey.

What wealth and for whom?

There are two final important methodological considerations: what assets are included

within the definition of total wealth and what is the appropriate economic unit to analyse.

While it would seem that defining someone’s wealth should be easy, in fact a judgement

needs to be taken on what is included within the definition of wealth. For example,

private pension assets are not readily convertible into other forms of wealth for someone

of working age and therefore have no direct impact on living standards, although

12 STRL data are (in some cases) reported for ‘families’ rather than individuals or households as defined in WAS. In our analysis of

the combined WAS and STRL data, we use household-level WAS data, and assume each observation in the STRL represents one

household. It is also worth noting that anecdotally there are a number of very high wealth families who are not covered by the STRL

data, not least because they may use vehicles such as trusts and foundations to hold wealth, making it difficult to identify their

wealth.

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

9

awareness of future pension receipts may affect one’s current desire to save. There is

no inherently correct answer but we have taken an approach which attempts to be as

comprehensive as possible. This means our primary definition of net wealth includes

all private pension assets, financial assets, other business assets, physical assets and

property assets net of formal and informal financial liabilities.

13

We do not include a

measure of the expected individual value for future public pension payments. Clearly

there is a relationship between the existence of public sector pensions and household

saving decisions (Lachowska and Myck, 2018) but there is no contractual obligation for

the government to maintain future pension payments at levels currently expected. In

which case, a consistent alternative to our approach would be to include the effective

value of an individual’s entitlement to the entire existing social security system. The

reasons we do not do this are twofold: this largely represents a level shift in wealth

holdings (albeit varying by age and other characteristics) and does not affect our analysis

of high wealth families, and this ‘wealth’ would not be relevant for a government if it were

considering introducing a wealth tax.

Finally, wealth can be measured for different economic units: individuals, families

(meaning single adults or couples with any dependent children) or households (meaning

everyone living in the same dwelling).

14

There are advantages and disadvantages of taking

different approaches. It is more natural to think about wealth as held by the family unit

given that resources are typically shared freely between members of a family. But there

tend to be differences between individuals within families – one obvious example is that

women tend to have much lower pension wealth as a result of lower average wages

and the likelihood of taking time out of the labour market for childcare (B&CE, 2019).

This means that analysis at the household or family level can under-represent some of

the inequalities in wealth holdings. Differences in the distribution of holdings across

definitions also matter for the revenue calculations of a wealth tax, depending on the

level at which it is planned to be levied. For the analysis which follows, we rely on wealth

per adult within family units. Appendices B, C and D repeat much of the analysis is

Section 3 based on alternative economic unit definitions.

13 Physical assets are inherently harder to value (e.g. replacement value vs market value vs insurance value) and the WAS survey

design does not always ask for consistent valuations for wealth. Since we wish to capture market value, we have reduced the

reported value of home contents, theoretically measured at replacement value, by 75% to be more consistent with market values

of other asset classes. This is likely a relatively conservative approach.

14 Often households and family units will overlap but not always – for example, family units would treat adult children living with

parents as separate families.

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

10

The distribution of UK household wealth

Inequality in household wealth

Household wealth in the UK is large and is held very unequally. Total net household

wealth as a share of national income has approximately doubled over the past thirty

years (Bangham and Leslie, 2020). Measures of wealth inequality suggest that it is twice

as unequally held as income (Crawford, Innes and O’Dea, 2016).

15

Understanding the size

and shape of wealth in the UK is vitally important for policymakers and is an important

context for the increasing interest in wealth taxes in the UK. This section explores the

topic in more depth.

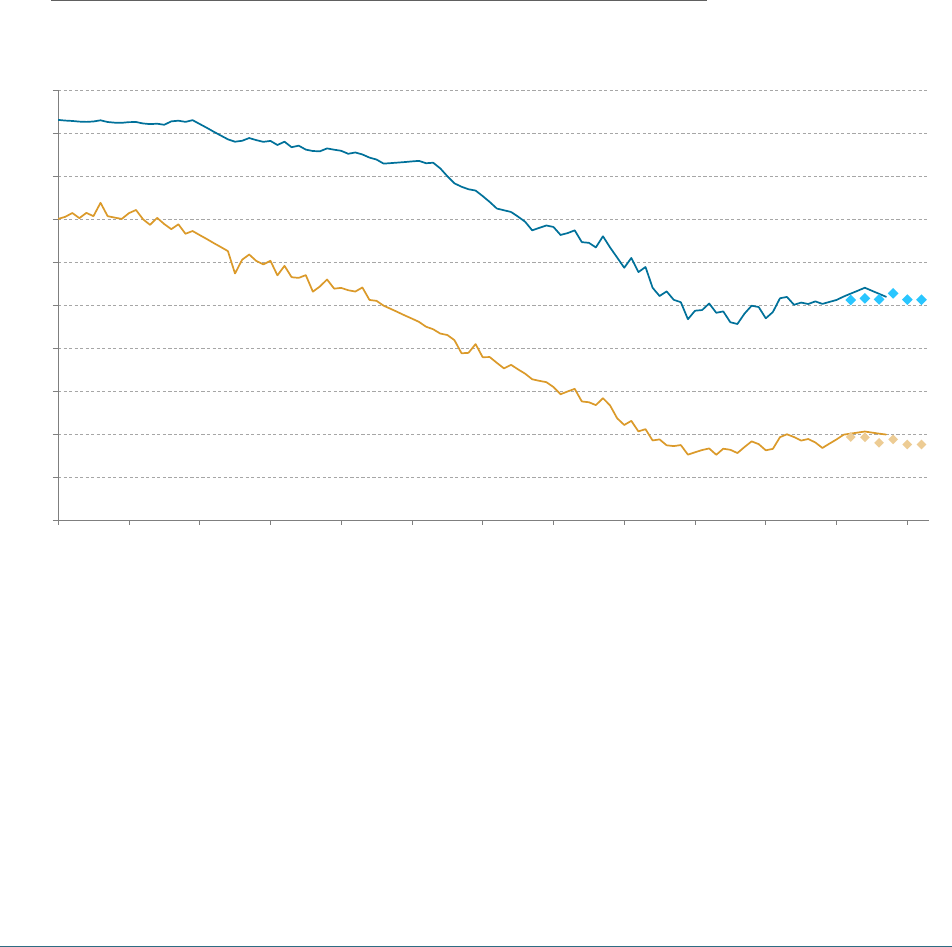

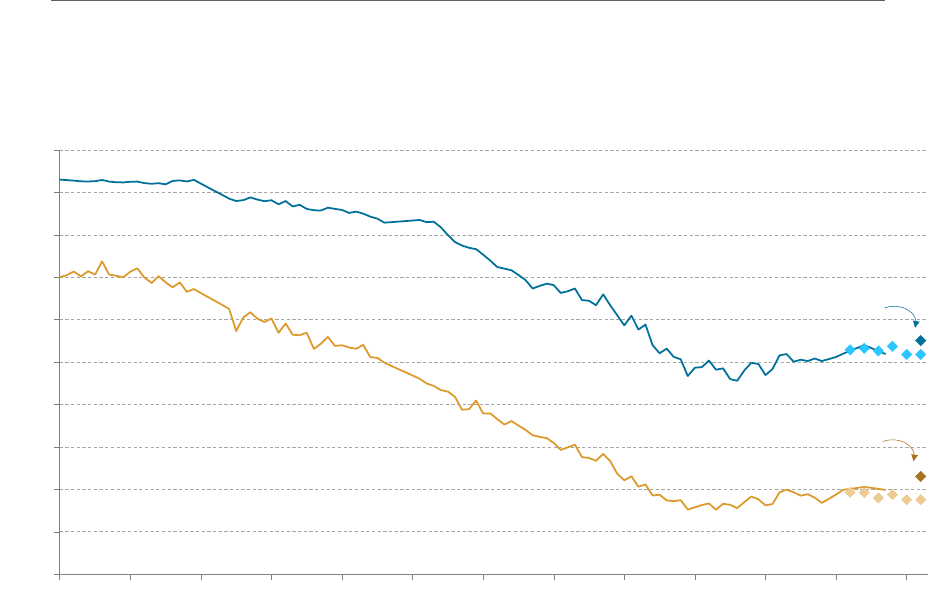

FIGURE 1: Wealth inequality fell for much of the 20th Century

Share of net personal wealth held by richest one and 10 per cent: UK and GB

NOTES: World inequality database estimates refer to the whole of the UK and the WAS-based estimates

exclude Northern Ireland. Due to changes in the coverage of business assets between survey rounds in

the WAS, these results are adjusted using the latest observation of private business wealth shares held by

the top 10% and 1% in the most recent round of the survey (2016–18) and imputed backwards to provide a

consistent estimate. The definition of wealth used for the long-run estimates is not consistent with that

from the WAS; Appendix A provides alternative estimates of top wealth shares which address some of

these differences.

SOURCE: World Inequality Database, 2020; ONS, Wealth and Assets Survey.

Long-run estimates of the UK wealth distribution (Figure 1) show that the share of wealth

at the top of the distribution fell markedly during the early and mid-twentieth Century,

15 However, recent work by Advani and Summers (2020) suggests income inequality is being under-measured, so is somewhat closer

to wealth inequality.

1 per cent share

10 per cent share

WAS-based

estimate

WAS-based

estimate

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1895 1905 1915 1925 1935 1945 1955 1965 1975 1985 1995 2005 2015

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

11

since then top wealth shares have remained fairly stable.

16

This is a trend which has been

repeated across many countries (Piketty, 2014). It is partially a function of similar changes

in income inequality; naturally, those with higher income are more likely to be able to

save and thus accumulate wealth over time. But, as discussed later, there are significant

macroeconomic trends which influence the size of wealth and the shape of the wealth

distribution which are unrelated to the broader trends affecting income inequality. In

other words, more recent changes in wealth are less to do with income and saving than

they would have been in the past.

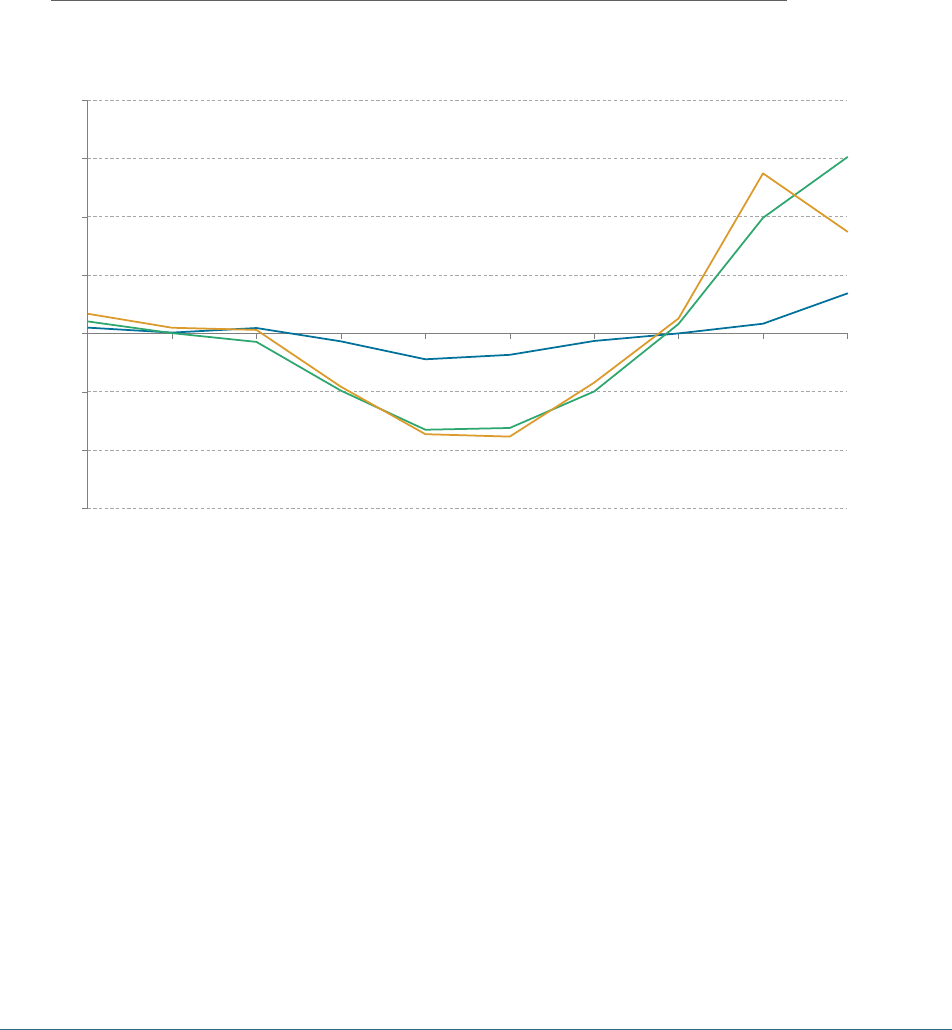

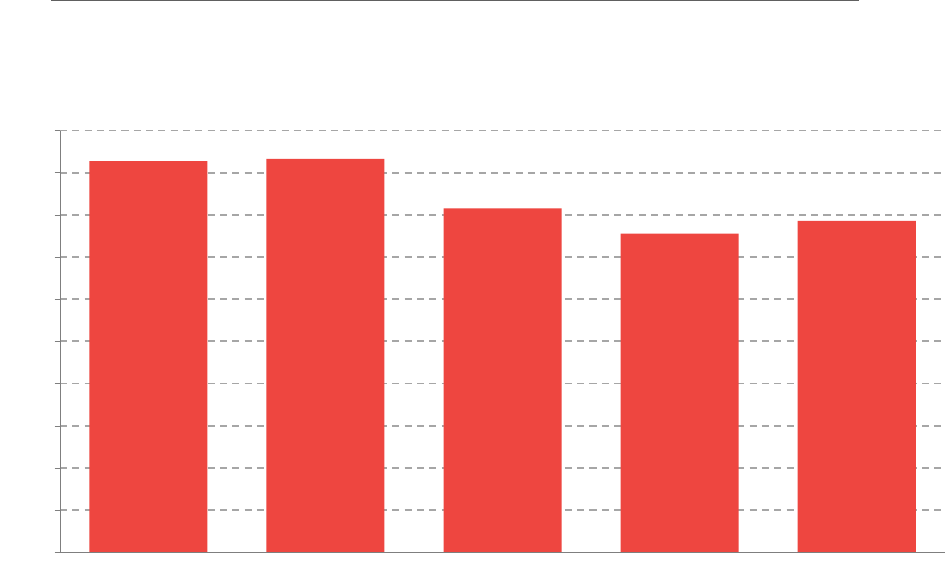

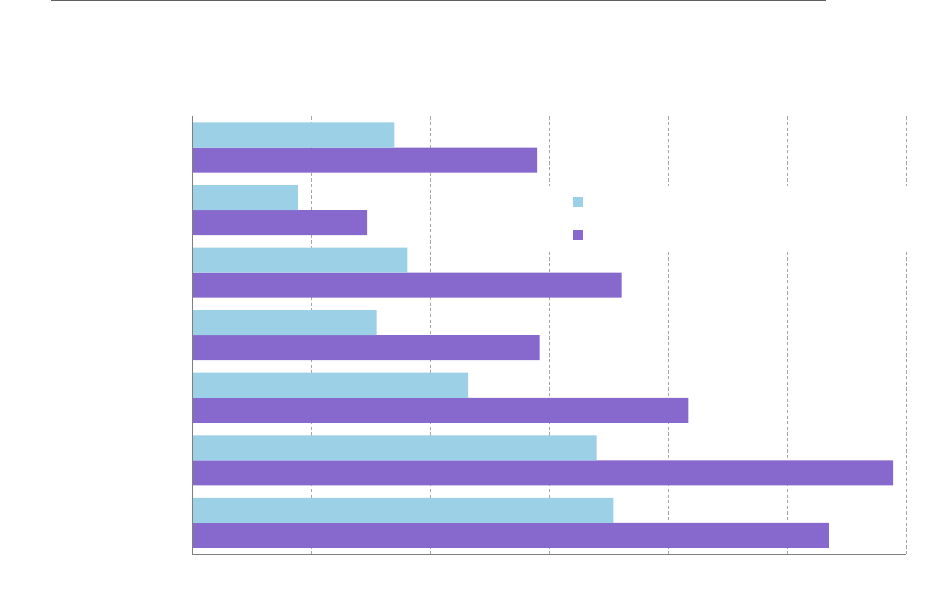

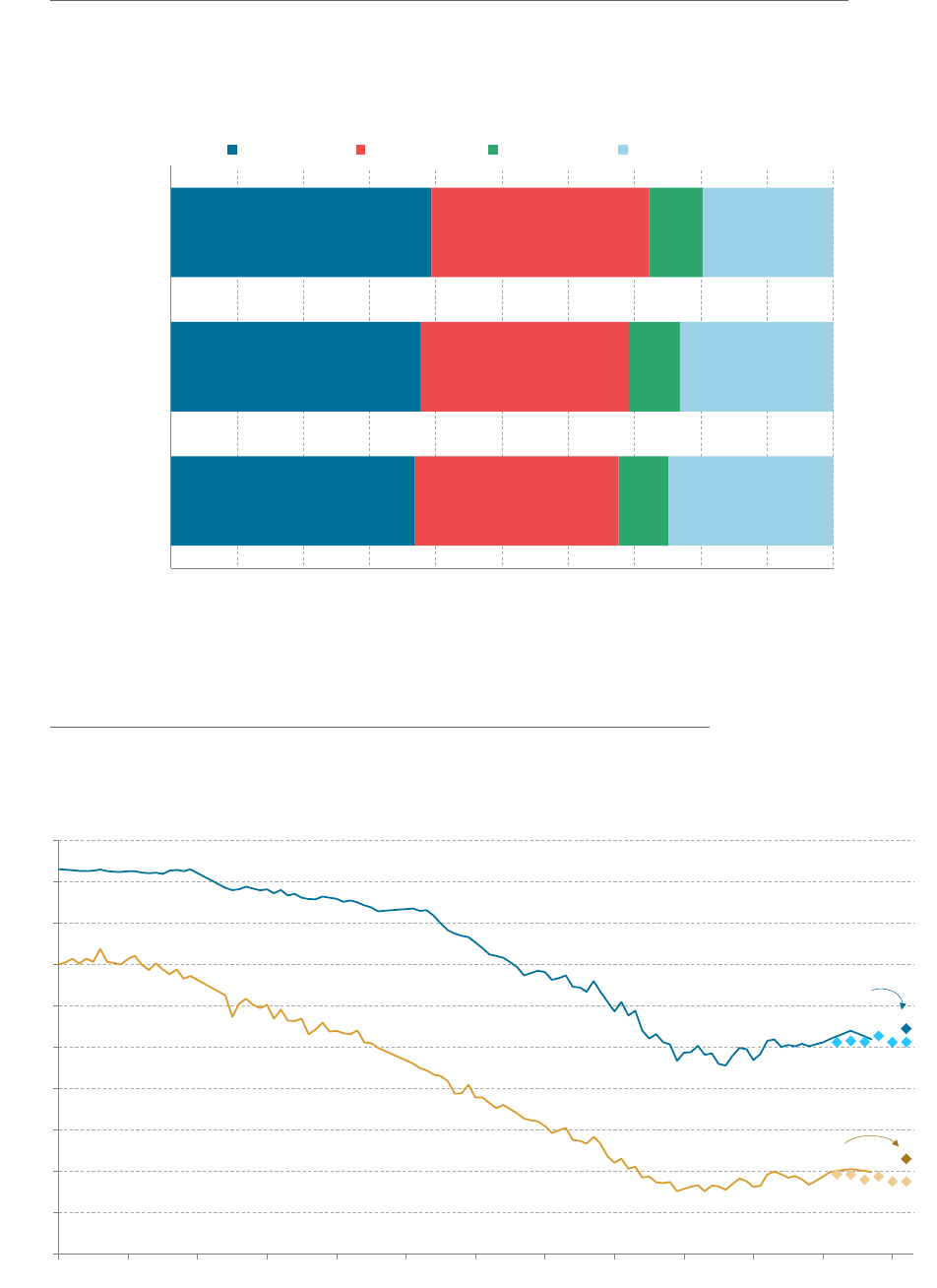

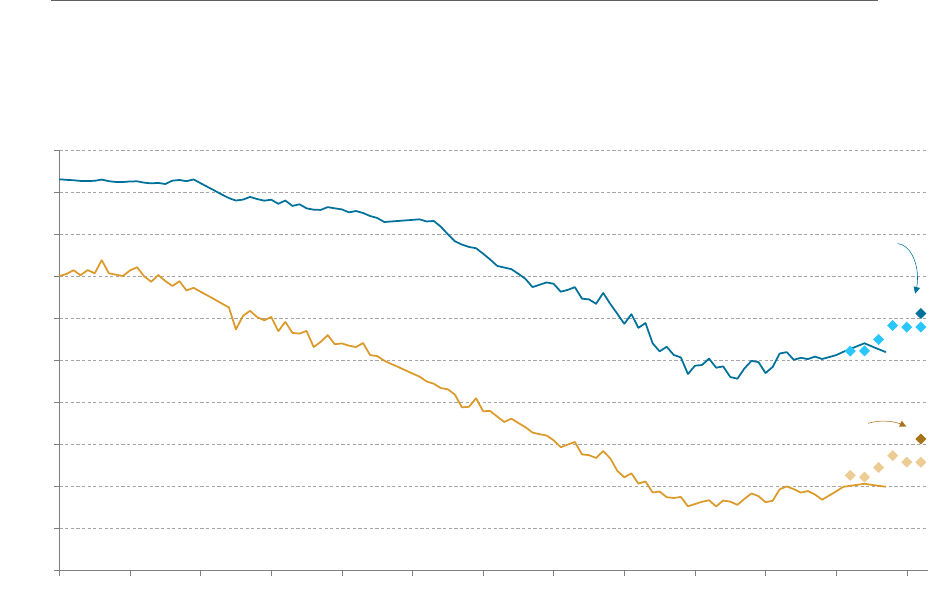

FIGURE 2: Wealth shares have fallen in the middle of the distribution

Share of total net family wealth by each net wealth decile since 2006-2008: GB

NOTES: Wealth is measured at the family level – single or couple adults and any dependent children

within a household. Total wealth includes net financial assets, net property assets, pension assets, and an

adjusted measure of physical wealth (including cars, home contents, collectibles, etc.). Private business

assets are excluded due to material improvements in the coverage of these assets since the early rounds

of the survey making cross-round comparisons difficult. Figure B1 shows the same graph constructed

using individuals as the unit of analysis.

SOURCE: ONS, Wealth and Assets Survey.

Drilling down into the available WAS data (which starts in 2006), we can see that there

has been a compositional shift in the wealth distribution: wealthier families hold a higher

share of wealth today than was the case a decade ago, while those in the middle hold

a smaller share of wealth (Figure 2). This shift is relatively small when compared to the

changes seen throughout the twentieth century. A commonly used alternative measure

of inequality, the Gini coefficient, has shown a very slight rise in inequality over this

16 We later show how these results are changed by the imputation of under-reported wealth. In Appendix A we also show that the

level and dynamics of wealth inequality in recent years depends on the definition of wealth used.

2008-10

2012-14

2016-18

-1.5ppts

-1.0ppts

-0.5ppts

0.0ppts

+0.5ppts

+1.0ppts

+1.5ppts

+2.0ppts

1

(lowest)

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

(highest)

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

12

period, going from 0.61 in 2006–2008 to 0.63 in 2016–2018 (ONS, 2019a). This suggests a

smaller rise in inequality than that implied by the rise in share of wealth held at the top,

because the increase in top-wealth shares has been offset by small improvements at the

bottom of the wealth distribution.

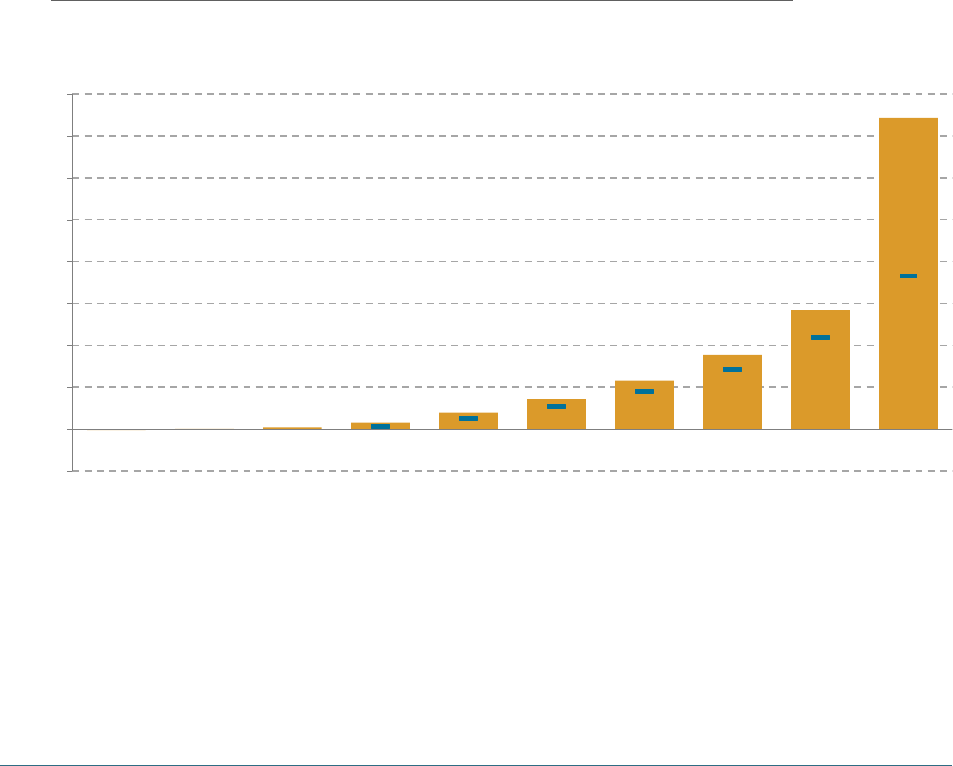

Unsurprisingly, wealth levels vary substantially across the distribution. The average family

in the poorest 10% of families has negative net wealth – i.e. their debts exceed their

assets, while the median family has just over £100,000 in net wealth per adult and the

top 1% has almost £5 million per adult in the family.

17

Figure 3a and b show the average

wealth holdings for each adult within family groups across the wealth distribution. The

large gaps between families has a profound effect on living standards as well as mobility

across the wealth distribution. To put the scale of these gaps in context, the UK median

net disposable household income was around £23,000 in 2018–19 (Brewer et al., 2020);

it would require more than 400 years for the median household saving all disposable

income to move from median wealth to reach the average wealth of the richest 1%.

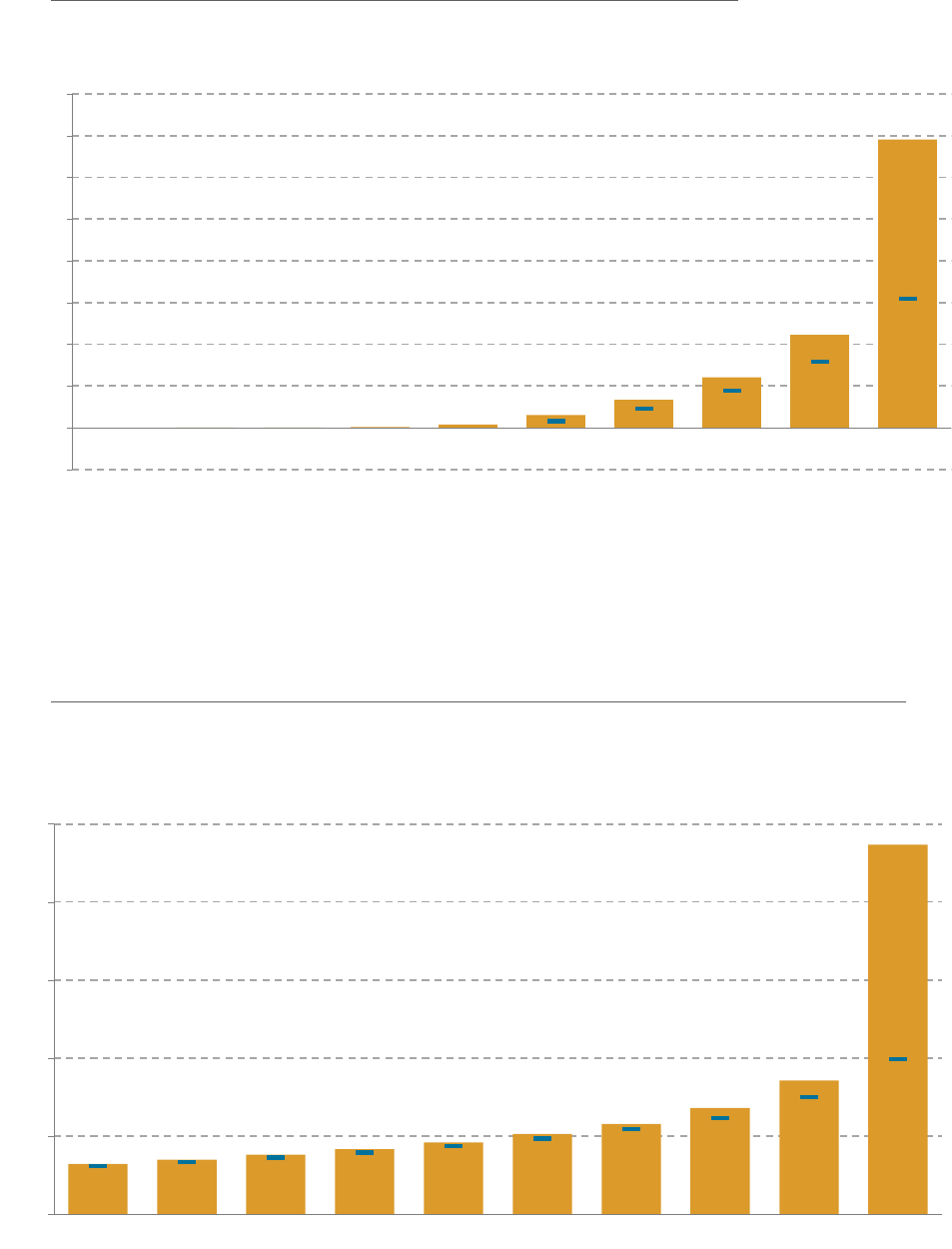

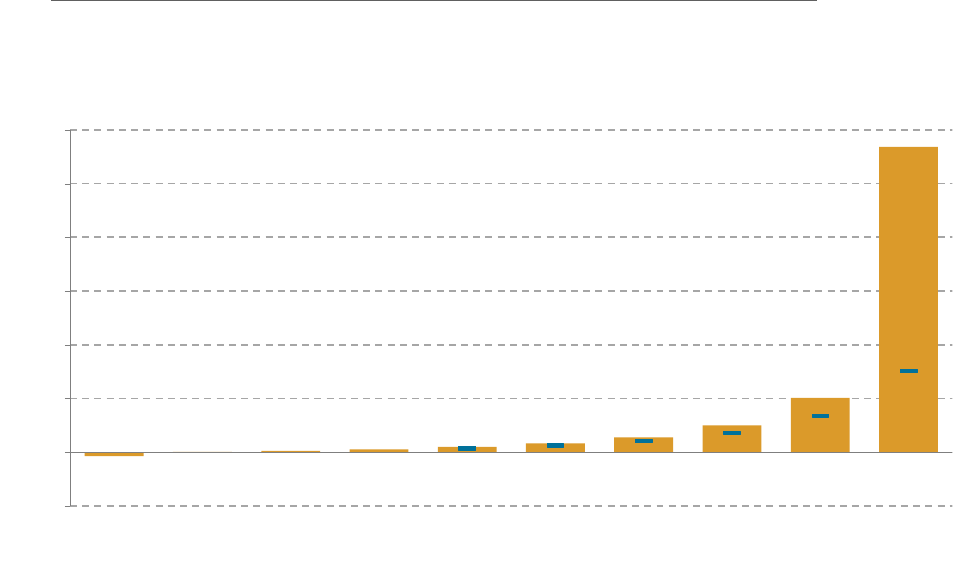

Figure 3a: Wealth holdings very widely across the wealth distribution

Average net wealth per adult per family within each net wealth decile: GB, 2016-2018

NOTES: Wealth is measured at the family level – single or couple adults and any dependent children within

a household. Total wealth includes net financial assets, net property assets, pension assets, business

assets and an adjusted measure of physical wealth (including cars, home contents, collectibles, etc).

Figures B2 and C1 show this graph using individuals and households as the unit of analysis, respectively.

Figure D1 shows this graph using an alternative wealth definition which excludes main homes and pension

wealth.

SOURCE: ONS, Wealth and Assets Survey.

17 Note that a family who are ‘just’ in the top 1% have £1.9 million wealth per adult. The mean per-adult wealth of a family in the

top 1% is much higher than this because it is an average that includes the extremely high wealth of those at the very top of the

distribution.

-£0.0m

£0.0m

£0.0m

£0.0m

£0.1m

£0.1m

£0.2m

£0.4m

£0.6m

£1.5m

-£0.2m

£0

£0.2m

£0.4m

£0.6m

£0.8m

£1.0m

£1.2m

£1.4m

£1.6m

1

(lowest)

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

(highest)

—

denotes minimum wealth within group

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

13

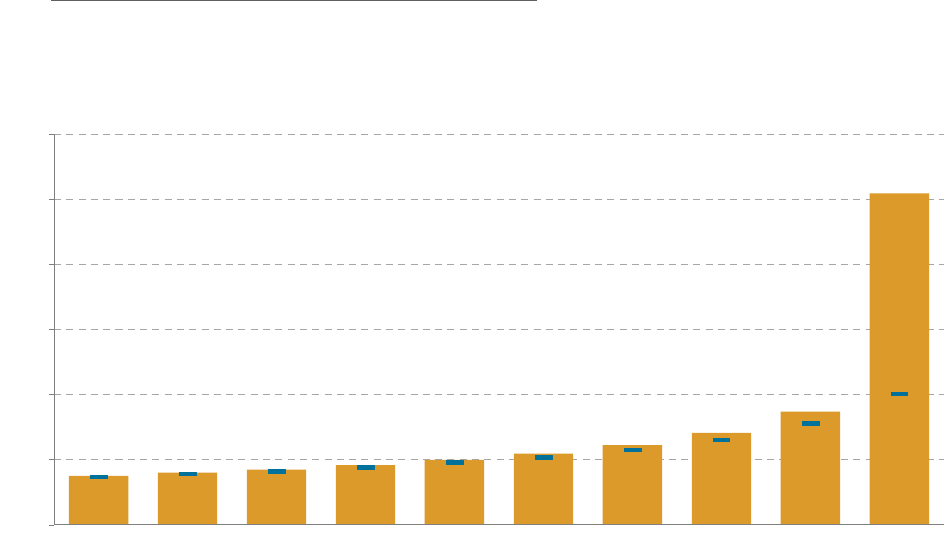

Figure 3b: The top 1 per cent are very wealthy

Average net wealth per adult per family within each net wealth percentile for the

wealthiest 10 per cent: GB, 2016-2018

NOTES: Wealth is measured at the family level – single or couple adults and any dependent children within

a household. Total wealth includes net financial assets, net property assets, pension assets, business

assets and an adjusted measure of physical wealth (including cars, home contents, collectibles, etc).

Figures B3 and C2 show this graph using individuals and households as the unit of analysis, respectively.

Figure D2 shows this graph using an alternative wealth definition which excludes main homes and pension

wealth.

SOURCE: ONS, Wealth and Assets Survey.

Composition of household wealth

Household wealth in the WAS is decomposed into five asset classes: property wealth

(net), physical wealth, private pension wealth, financial wealth (net), and business assets.

Net property wealth consists of self-valuations of any property owned by the household,

net of any loans or mortgages secured on the property. Physical wealth includes the

estimated value of all household contents, including antiques, artwork, and vehicles.

Private pension wealth is the value of all occupational and personal pensions, including

both defined contribution and defined benefit pensions, as well as pensions in payment.

Financial wealth includes the value of formal investments such as bank or building

society current or savings accounts, ISAs, endowments, stocks and shares, informal

savings, and childrens’ assets, less financial liabilities. This includes shares in public and

private corporations, the main source of wealth measured in the Sunday Times Rich List.

Business assets, in contrast, include the value of assets used within a business in which

the respondent is self-employed, or is a director or partner. This includes unincorporated

businesses, and is unlikely to closely match the STRL concept of ‘business wealth’, which

largely reflects shares in public or private corporations.

£0.8m £0.8m £0.8m £0.9m £1.0m £1.1m £1.2m £1.4m £1.7m £5.1m

£0

£1m

£2m

£3m

£4m

£5m

£6m

91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100

—

denotes minimum wealth within group

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

14

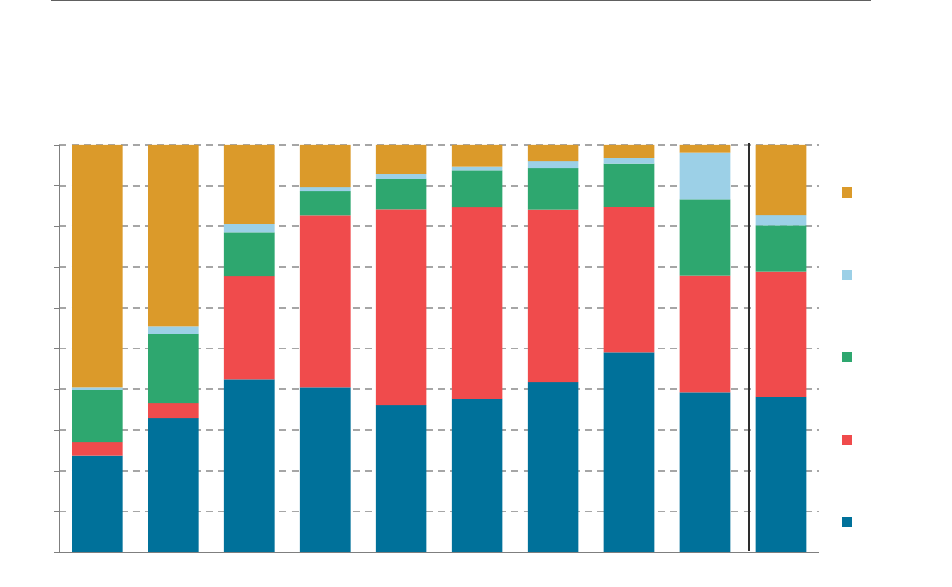

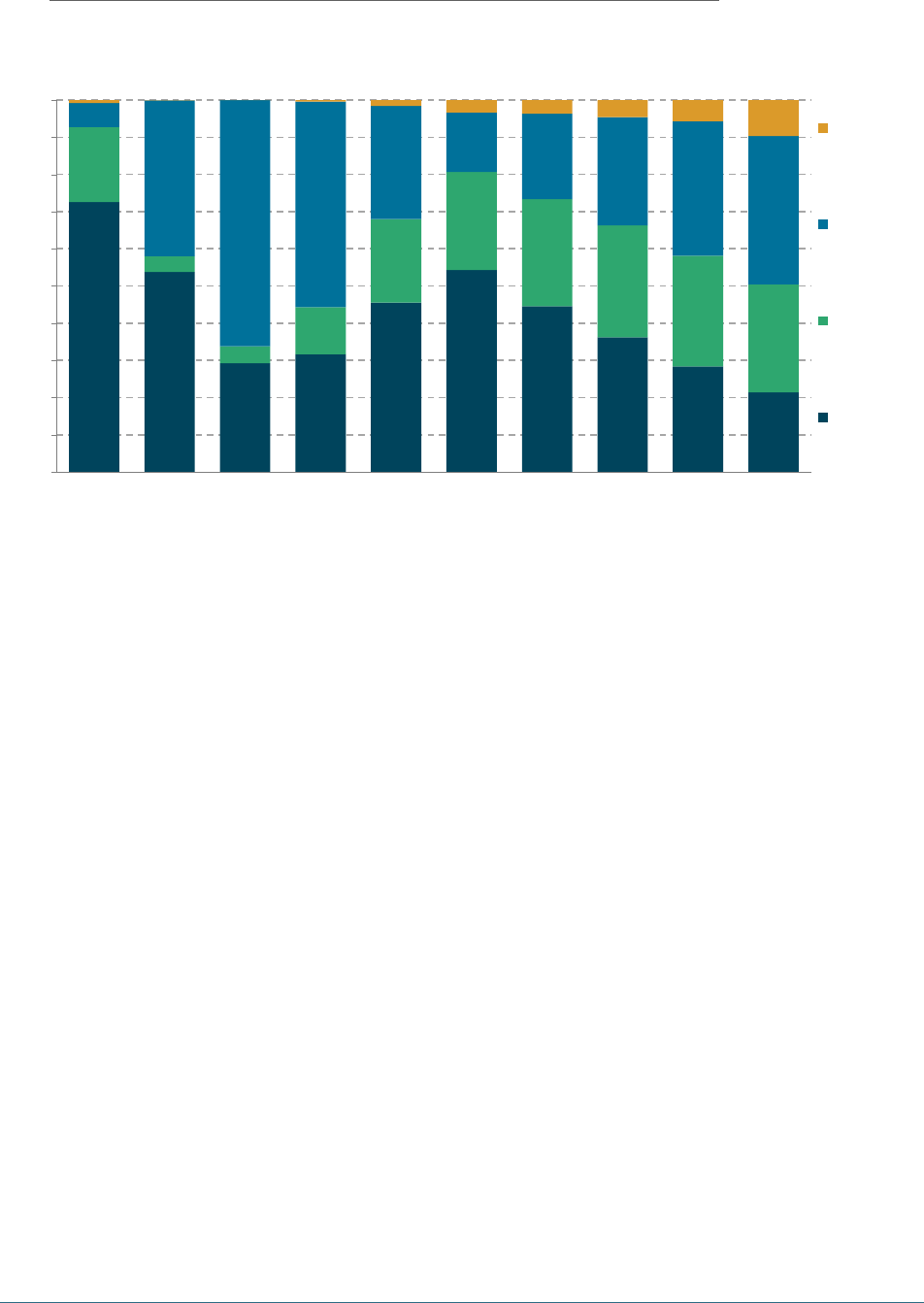

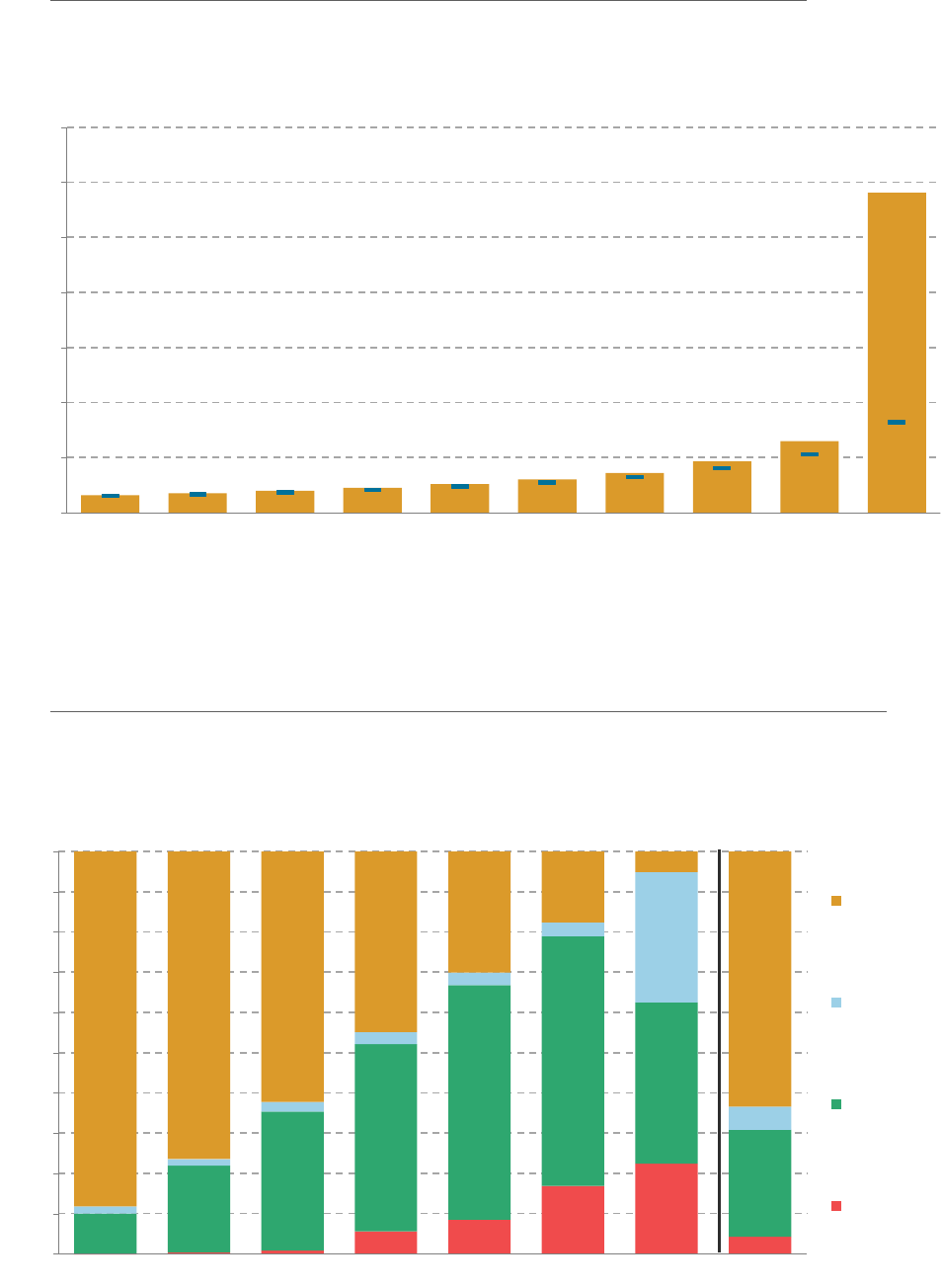

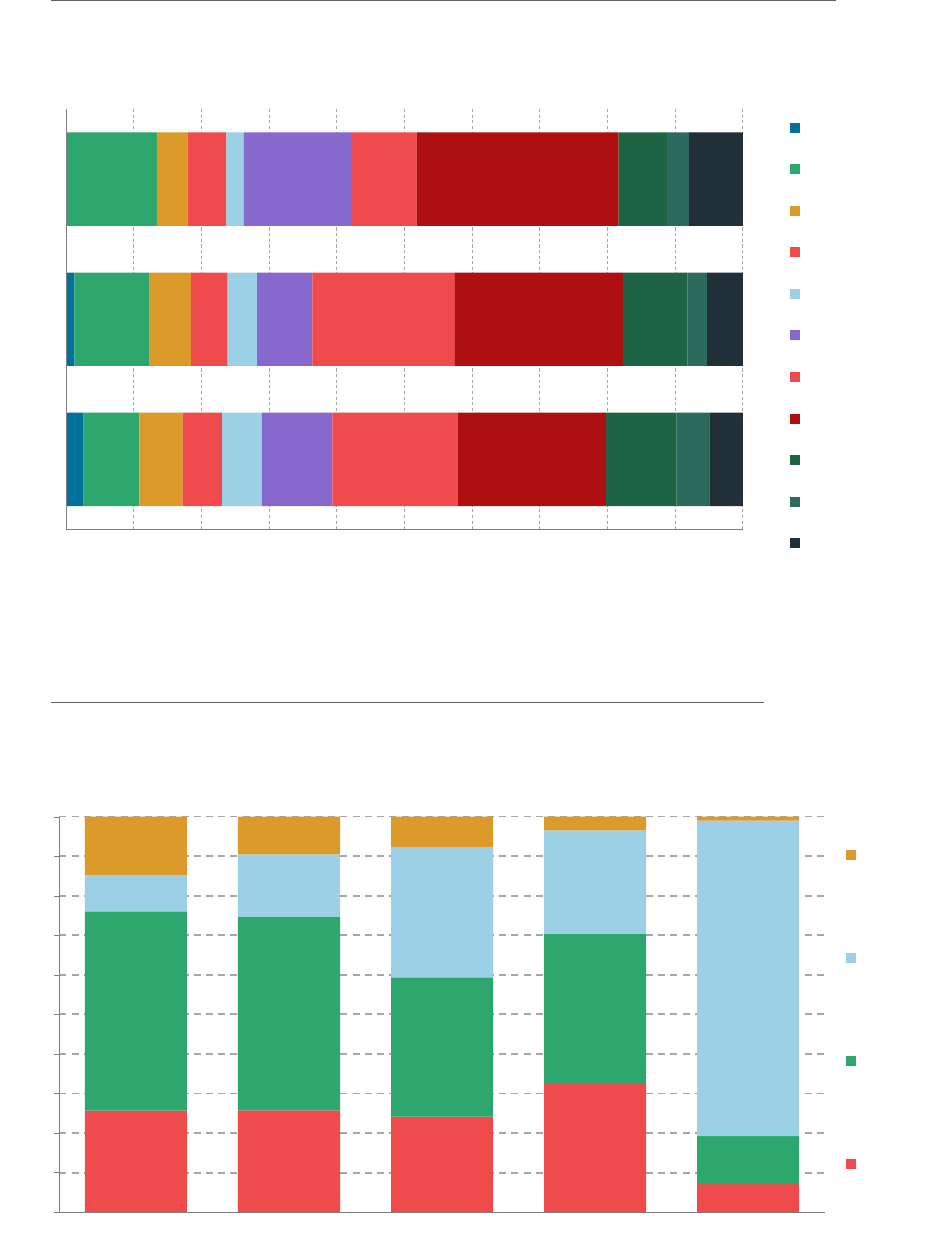

There is significant heterogeneity in the types of assets held by families across the

wealth distribution (see Figure 4). Poorer families tend to have very little gross property

or financial wealth and are more likely to have financial debts exceeding assets than

a typical family – this means that physical assets make up a much higher proportion

of their overall wealth. This pattern reverses for wealthier families: net property wealth

is the most important source of wealth for the fifth, sixth, seventh and eighth deciles,

while physical assets make up a very small share of the total wealth for the richest

families. Pension assets make up the largest source of net wealth of all asset types and

is remarkably stable across the wealth distribution at the fourth decile and above. Poorer

households are much less likely to have private pension wealth, likely reflecting lower

capacity to save for retirement due to low income, although there is some evidence that

in recent years more families across the wealth distribution now have access to defined

contribution pension wealth as a result of auto-enrolment (Slaughter, 2020).

FIGURE 4: Business assets are much more prevalent at the top of the wealth

distribution

Average share of total net wealth contributed from different asset classes by family net

wealth decile: GB, 2016–2018

NOTES: Individuals are allocated to deciles based on wealth measured at family level. The lowest decile is

excluded as net wealth is negative. Property wealth here is measured net of mortgage debt and financial

wealth is net of other financial liabilities. Figure C3 shows this graph using households as the unit of

analysis. Figure D3 shows the average share of total net wealth contributed from different asset classes

when main homes and pension wealth are excluded.

SOURCE: ONS, Wealth and Assets Survey.

24%

33%

42%

40%

36%

38%

42%

49%

39%

38%

3%

4%

25%

42%

48%

47%

42%

36%

29%

31%

13%

17%

11%

6%

7%

9%

10%

11%

19%

11%

60%

45%

19%

10%

17%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Average

Physical

Business

Financial

Property

Pension

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

15

FIGURE 5: Wealthier families hold more higher-returning riskier assets

Composition of financial assets by family net wealth decile: GB 2016–2018

NOTES: Individuals are allocated to deciles based on total wealth measured at family level. Zero-return

assets include cash, current accounts and other informal financial assets. Savings assets include savings

accounts (i.e. interest-bearing sight deposit accounts) and national savings products. Safe assets include

ISA accounts,18 saving bonds (i.e. fixed term saving accounts), unit and investment trusts, insurance

products and other formal financial assets. Risky assets include domestic and overseas shares and bonds.

Figure B4 shows this graph using individuals as the unit of analysis.

SOURCE: ONS, Wealth and Assets Survey.

Changes in wealth levels

Financial Wealth

A hugely important trend for financial wealth has been the scale of the aggregate

increase in its value; since 2006–08 total financial wealth in Great Britain has increased

by more than 60% in real terms (from £1.4 trillion to £2.3 trillion) in current CPI-adjusted

prices. This represents a remarkable increase in the wealth families hold. Bangham and

Leslie (2020) and Mulheirn (2020) show that the increase in financial wealth over this

period has been overwhelmingly driven by changes in asset prices rather than active

saving by individuals.

Figure 6 shows the estimated share of families’ change in financial wealth as a result of

changes in financial asset prices and financial market yields. This analysis exploits the

longitudinal nature of the WAS. Concretely, the change in financial wealth of each family

is calculated for each adjacent two-year period of the survey. A counterfactual financial

wealth value is calculated by applying the average returns observed for a granular

18 This includes both cash ISAs (which would be more similar to savings assets in this taxonomy) and stocks and shares ISAs. We

have included both within the ‘safe assets’ group because both these ISA accounts would typically have a higher yield than non-

ISA savings accounts.

71%

57%

54%

47%

44%

38%

32%

27%

23%

17%

13%

14%

19%

25%

25%

27%

29%

29%

30%

28%

16%

29%

26%

25%

27%

30%

34%

38%

41%

43%

4%

5%

6%

6%

7%

11%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1

(lowest)

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

(highest)

Risky

assets

Safe assets

Savings

assets

Zero-return

assets

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

16

breakdown in financial asset classes over the relevant two-year period. Between 2008–10

to 2010–12, for example, 93% of the average change in families’ financial wealth could be

accounted for by changing asset prices and financial market yields. The remaining wealth

change is the net saving of the family over this period.

This fact is important context for understanding how wealth has changed in the UK: to a

large extent, wealth gains for families have accrued as a result of already holding wealth –

wealth gains have been passive rather than requiring active saving. This also is important

for any government considering the taxation of wealth as people are likely to feel it is

more justifiable for a government to tax ‘unearned’ gains in wealth rather than those

which come about through ‘virtuous’ action like working more or saving (Sachweh and

Eicher, 2020; Rowlingson, Sood and Tu, 2020).

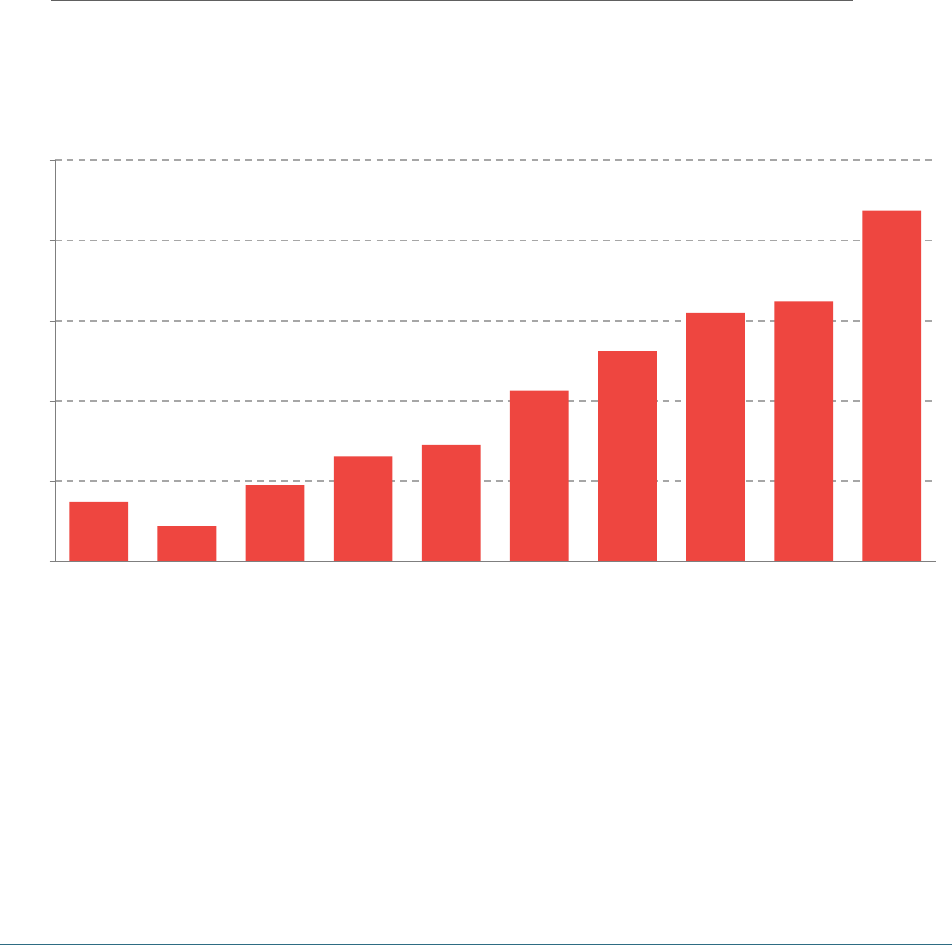

FIGURE 6: Almost all the gains in financial wealth since 2006-08 have come

from changes in asset prices rather than saving

Share of total average gains in financial wealth from changes in asset prices: GB

NOTES: Total changes in family financial wealth is measured between each two-year sample of the WAS.

This is compared to a counterfactual change in wealth predicted by average financial returns for a granular

breakdown of assets. This is then used to calculate the share of the observed change in wealth that would

on average have resulted from financial returns.

SOURCE: Bangham and Leslie (2020).

Increasing financial wealth has also tended to accrue to the already wealthy. As already

shown, wealthier households tend to hold financial assets which have more risk but also

tend to have higher average returns. In simple terms, a household holding a portfolio of

company shares will have experienced a larger increase in wealth than one who held

the same wealth in a savings account which in turn had a higher return than cash (see

93%

93%

82%

76%

79%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2008-10 2010-12 2012-14 2014-16 2016-18

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

17

also Bach, Calvet and Sodini, 2020; Fagereng et al., 2020). Figure 7 presents a crude

estimate of this in-built acceleration of wealth inequality whereby richer households will

tend to experience faster gains in wealth. This estimate is calculated as the weighted

average return for the average financial portfolio for a family within each decile based on

granular financial asset classes. This is not an estimate of the actual return experienced

by families because real returns will diverge from the average, and this divergence may

differ across the wealth distribution.

19

Saez and Zucman (2016) argue that divergences

in returns across the wealth distribution has been one of the most important drivers in

rising wealth inequality in the US over the past few decades.

FIGURE 7: Wealthier families tend to experience higher financial returns to

their assets

Mean annual financial asset return based on differences in portfolio composition, by

family net wealth decile: GB, 2016–2018

NOTES: A family’s financial return is calculated as an average of the observed average annual financial

returns for a granular set of financial assets weighted by their financial asset portfolio composition. Each

family’s calculated financial return is average within net family total wealth deciles. This does not show the

actual returns experienced by each family as this is not observed in the WAS data.

SOURCE: Bangham and Leslie (2020).

Pension Wealth

Financial wealth is not the only category of wealth which has experienced increases

in value over the past decade. Aggregate private pension wealth has also increased

in value by more than 60% since 2006–2008 (ONS, 2019a). In practice, the drivers of

19 Indeed, Fagereng et al. (2019) show that richer households in Norway tended to achieve higher than average returns within asset

classes. Similarly, Bach, Calvet and Sodini (2020), show that returns on wealth are highly persistent and are positively related to

existing wealth levels. The estimates presented here are therefore likely to be an underestimate of the divergence between richer

and poorer families.

0.4%

0.2%

0.5%

0.7%

0.7%

1.1%

1.3%

1.5%

1.6%

2.2%

0.0%

0.5%

1.0%

1.5%

2.0%

2.5%

1

(lowest)

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

(highest)

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

18

increased pension wealth are similar to those affecting financial wealth because

the majority of assets underlying the value of pension funds are financial assets. In

particular, the secular decline in interest rates around the world as central banks cut

rates and conducted quantitative easing to counteract the post-financial crisis economic

slowdown, has lifted the price of financial assets around the world.

20

An important

difference between financial wealth and pension wealth is that rises in pension wealth

levels have a lower impact on relative inequality because pension wealth is held more

equally across the wealth distribution.

Property Wealth

Property wealth gains have been much lower over the past decade, rising by just 14% in

real terms. While interest rates falls push up property prices all else equal, and explain a

large part of the rise in property values (Mulheirn, 2019; 2020; Miles and Monro, 2019), falls

in mortgage rates have tended to be smaller than the falls central bank rates. Outside the

South of England, real house prices have been largely flat since the pre-financial crisis

peaks, limiting the gains that many families have experienced in property wealth. The

relatively slow growth in property wealth is a major driver of the declining share of wealth

in the middle of the distribution, as property wealth makes up a much larger share of

wealth for middle-wealth families (Figure 4).

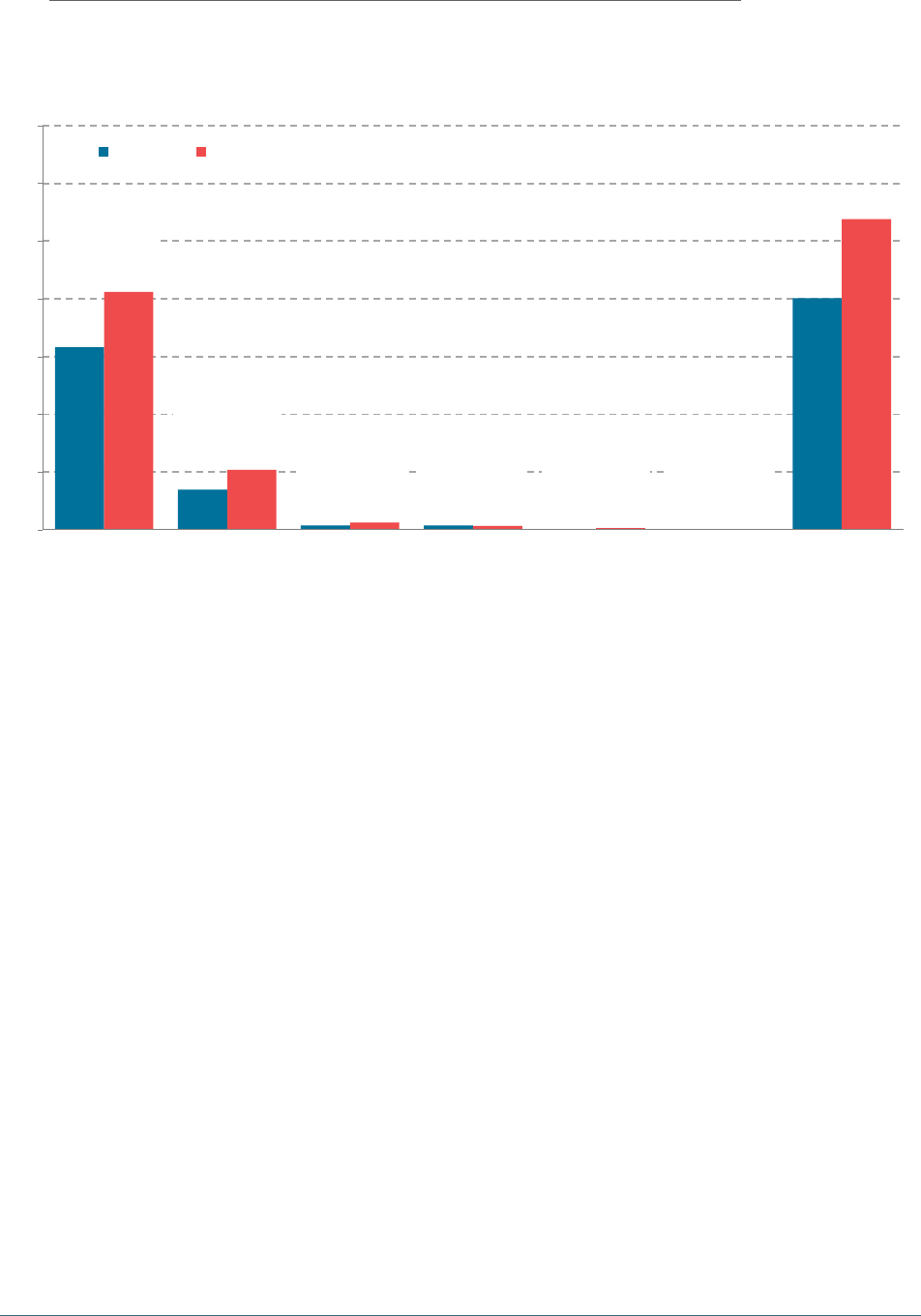

Demography

As we have shown, the major driver of the changing size and distribution of wealth

has been the returns to financial and pension wealth and the (relative) lack of returns

to property wealth over the past decade. But there is another potentially important

factor: demographic changes – particularly the ageing population. An individual’s wealth

changes substantially over the course of their life, with families tending to build up

wealth over working age before drawing down wealth somewhat in retirement (D’Arcy

and Gardiner, 2017). The UK population has been ageing and is expected to continue to

do so; between 2006 and 2019 the share of the population between 20 and 39 years old

fell from 27.3% to 26.3% and is expected to fall to 24.5% by 2040 (ONS, 2019b). There has

been a commensurate increase in older workers and retired people. This would naturally

lead to a shift in the distribution of wealth however, as shown in Figure 8, the estimated

effect of the ageing population has been small relative to the scale of the overall shift in

wealth shares across the wealth distribution.

20 See Gangon et al. (2019) for more detail on the impact of quantitative easing on wealth inequality in the UK.

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

19

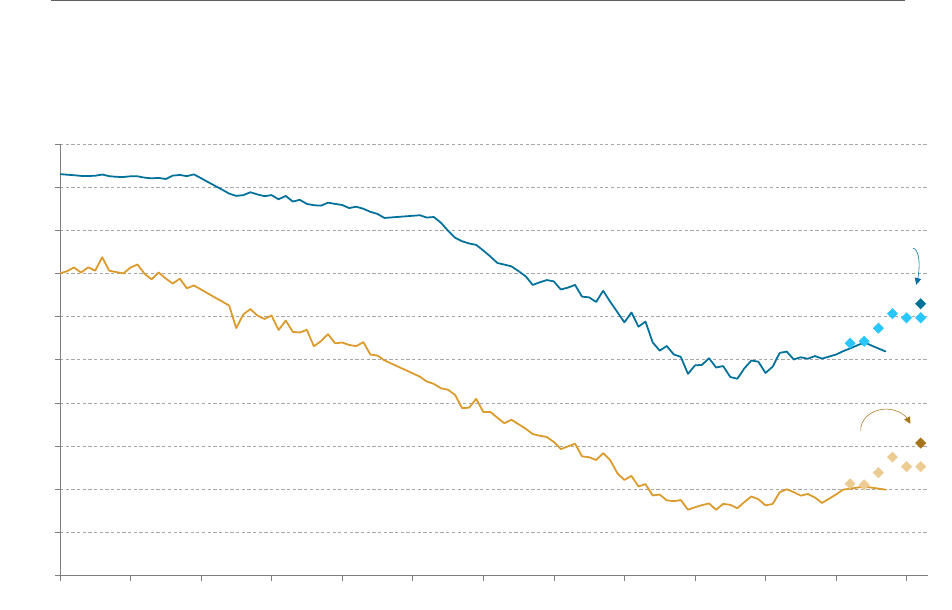

FIGURE 8: The impact of population has been relatively small

Estimated change in share of wealth for each net family wealth decile due to population

ageing: GB

NOTES: These estimates are calculated by reweighting the WAS sample from 2006–2008 to match the

2019 age distribution and the 2016–2018 WAS sample to match the 2040 projected age distribution. This

estimate therefore abstracts from cohort effects.

SOURCE: ONS, Wealth and Assets survey; ONS population estimates.

Characteristics of high-wealth households

Much of the political focus on inequality in the UK and around the world focusses

on the people who are at the top of the distribution. This section tries to explore the

characteristics of families which could be considered high-wealth. As high-wealth is

a subjective term, we use five thresholds as markers of high wealth families: families

where the per adult net wealth exceeds £250,000, £500,000, £1 million, £2 million and £5

million. These thresholds broadly range from households in the top 40% of the wealth

distribution to the top 1%. In practice, this analysis is also useful for understanding the

characteristics of families which may be subject to plausible thresholds for a net wealth

tax. As such we might also be interested in the characteristics of those with wealth

above these thresholds for a more restrictive definition of wealth that could be adopted

for a wealth tax; Appendix E reproduces the results below where total wealth is defined to

exclude wealth from main residential properties and pensions.

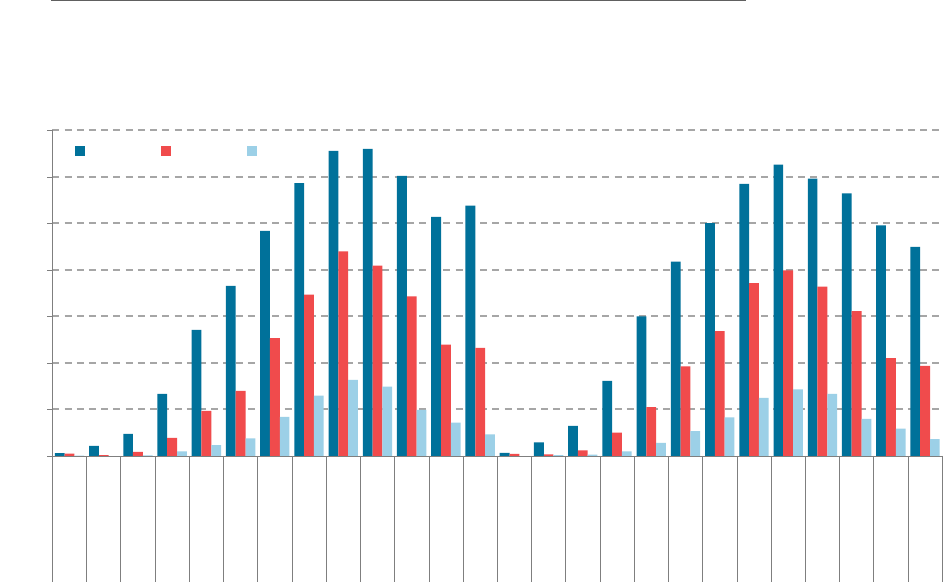

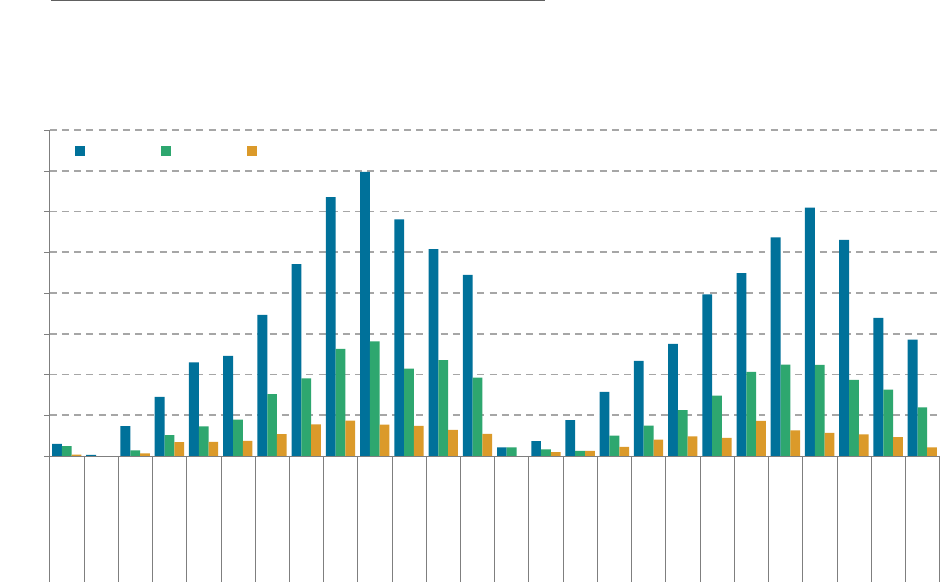

Demographic characteristics

There are large differences in the probability of an individual living in a high wealth

family across age and sex (Figure 9a and b). There is a clear tendency for older people

to live in high wealth families. This is unsurprising given the strong life-cycle effects

in wealth but will also partially reflect cohort effects whereby older generations were

-0.04ppts

-0.02ppts

0.00ppts

+0.02ppts

+0.04ppts

+0.06ppts

+0.08ppts

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

2006-2019

2019-2040

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

20

able to accumulate wealth at a faster rate than younger generations. Men are also

more likely than women to live in high-wealth families, largely reflecting the fact that

single men are more likely to be high wealth than single women. The biggest disparity

in high-wealth families by age is for those with per-adult wealth above £2 million, where

families are much more likely to be late working age or early retirement. However, the

pattern switches at a threshold of £5 million to having much less variation by age. This is

consistent with the lifecycle consumption-smoothing motivation for savings being a less

important driver of wealth accumulation and decumulation at this high level of wealth.

Figure 9a: Older people are much more likely to have high wealth

Share of age and sex group that live in high-wealth families (above £250,000 per adult):

GB 2016–2018

NOTES: Wealth thresholds are measured as total wealth per adult within the family. Figure E1 shows this

graph using an alternative definition of wealth that excludes main homes and pension wealth.

SOURCE: ONS, Wealth and Assets Survey.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

20-

24

25-

29

30-

34

35-

39

40-

44

45-

49

50-

54

55-

59

60-

64

65-

69

70-

74

75-

79

80+ 20-

24

25-

29

30-

34

35-

39

40-

44

45-

49

50-

54

55-

59

60-

64

65-

69

70-

74

75-

79

80+

£250k £500k £1m

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

21

Figure 9b: The very wealthiest families are more evenly spread over the age

distribution

Share of age and sex group that live in high-wealth families (above £2 million per adult):

GB 2016–2018

NOTES: Wealth thresholds are measured as total wealth per adult within the family. Figure E2 shows this

graph using an alternative definition of wealth that excludes main homes and pension wealth.

SOURCE: ONS, Wealth and Assets Survey.

Additionally, the variation in wealth holdings between households of different ethnicities

is striking, and is under-studied due to the scarcity of relevant data. Figure 10 shows the

proportion of households with total net wealth above £250,000 and above £500,000.

21

It shows that households whose Household Reference Person is of White ethnicity are

most likely to have total net wealth of £500,000 or more, closely followed by those of

Indian ethnicity.

22

The sample size precludes us from examining all of the ethnic minority

groups available in the data individually, but Figure 10 can tell us that households of Black

African ethnicity are least likely to have net wealth over the £500,000 threshold, and four

times less likely than those of White ethnicity.

21 Sample sizes become too small to present results for higher wealth thresholds. It is also important to note that this is a different

unit of analysis from the other charts in this section, as a result of needing to use a more data-secure version of the WAS dataset

to conduct analysis by ethnicity.

22 Ethnic group is based on the Household Reference Person’s reported ethnicity – this is the survey-designated primary adult within

the household. Where the individuals within a couple have different ethnicities, this will not be captured by our estimates.

0.0%

0.5%

1.0%

1.5%

2.0%

2.5%

3.0%

3.5%

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

20-

24

25-

29

30-

34

35-

39

40-

44

45-

49

50-

54

55-

59

60-

64

65-

69

70-

74

75-

79

80+ 20-

24

25-

29

30-

34

35-

39

40-

44

45-

49

50-

54

55-

59

60-

64

65-

69

70-

74

75-

79

80+

£2m £5m

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

22

FIGURE 10: White and Indian families are more likely to have high wealth

Share of households above wealth thresholds within ethnicity groups, by ethnicity of

Household Reference Person

NOTES: Wealth thresholds are measured as total wealth per adult within the family. Individuals reporting

Chinese, Mixed and Other ethnicities are combined due to restrictions on the minimum sample size that

can be analysed.

SOURCE: Office for National Statistics, Social Survey Division. (2020). Wealth and Assets Survey, Waves 1-5

and Rounds 5-6, 2006-2018: Secure Access. [data collection]. 6th Edition. UK Data Service. SN: 6709. DOI:

http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-6709-5

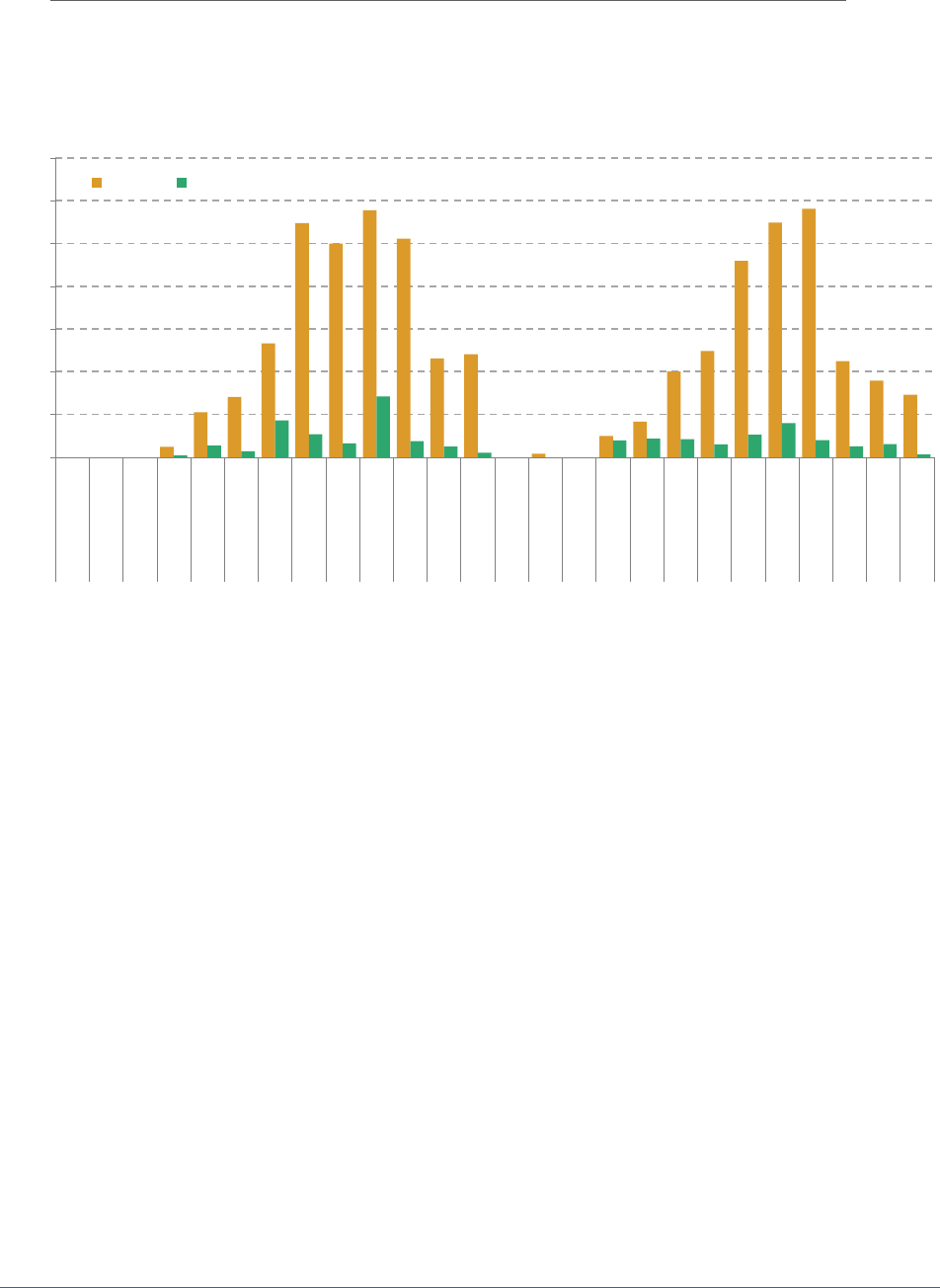

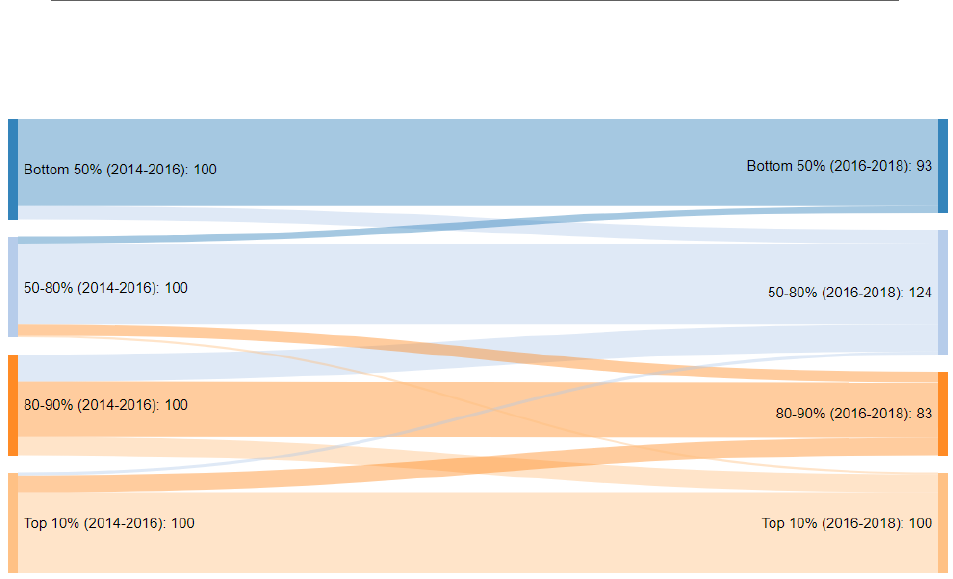

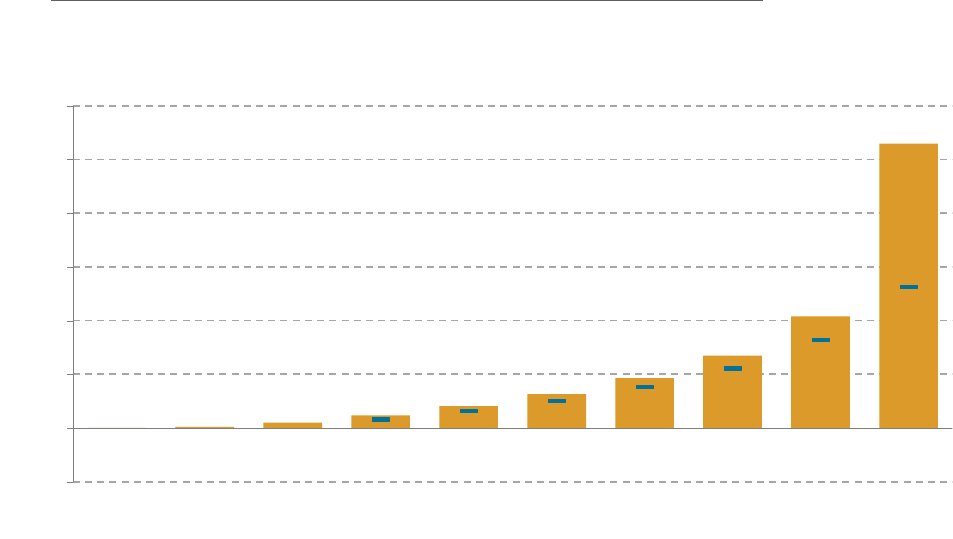

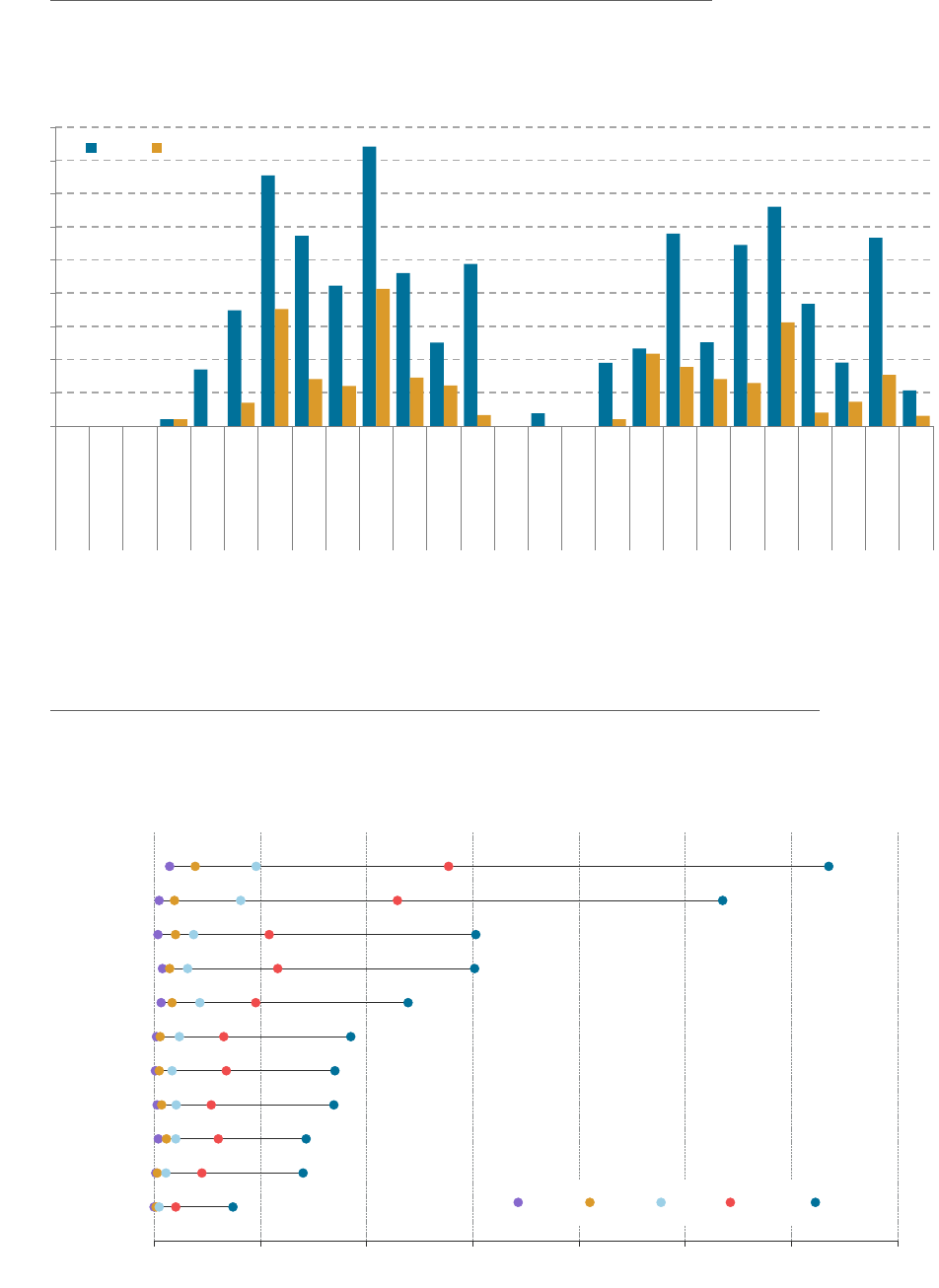

Geography

Another characteristic of interest is the geographic distribution of high wealth families.

As Figure 11 shows, the South East of England has the highest number of high-wealth

families, with well over 3 million adults living in families with net wealth per adult over

£250,000. The North East is the region with the lowest proportion of high-wealth families.

Figure 12 shows the share of the total number of families which are above the wealth

threshold coming from each region. This shows that the large regional disparity in high-

wealth families magnifies as the threshold increases. For example, 14% of all families with

per-adult wealth above £250,000 are in London but this share rises to 24% for families

with wealth above £2 million.

54%

59%

42%

29%

36%

15%

29%

35%

34%

23%

16%

18%

9%

17%

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60%

White

Asian - Indian

Asian - Pakistani

Asian - other

Black Caribbean

Black African

Mixed, Chinese, other

Proportion with wealth of £500k or more

Proportion with wealth of £250k or more

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

23

FIGURE 11: The South and East of England have the highest numbers of wealthy

families

Number of high-wealth individuals by threshold level, calculated at the family level: GB,

2016–2018

NOTES: Wealth thresholds are measured as total wealth per adult within the family. Figure E3 shows this

graph using an alternative measure of wealth which excludes main homes and pension wealth.

SOURCE: ONS, Wealth and Assets Survey.

FIGURE 12: London and the South East of England have the highest share of

wealthy families

Share of all families above wealth threshold by region: GB 2016–2018

NOTES: Wealth thresholds are measured as total wealth per adult within the family. Figure E4 shows this

graph using an alternative measure of wealth which excludes main homes and pension wealth.

SOURCE: ONS, Wealth and Assets Survey.

South East

London

East of England

South West

North West

Scotland

West Midlands

Yorkshire

East Midlands

Wales

North East

0 0.5m 1.0m 1.5m 2.0m 2.5m 3.0m 3.5m

£5m £2m £1m £500k £250k

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

£250k

£1m

£5m

North East

North West

Yorkshire

East Midlands

West Midlands

East of England

London

South East

South West

Wales

Scotland

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

24

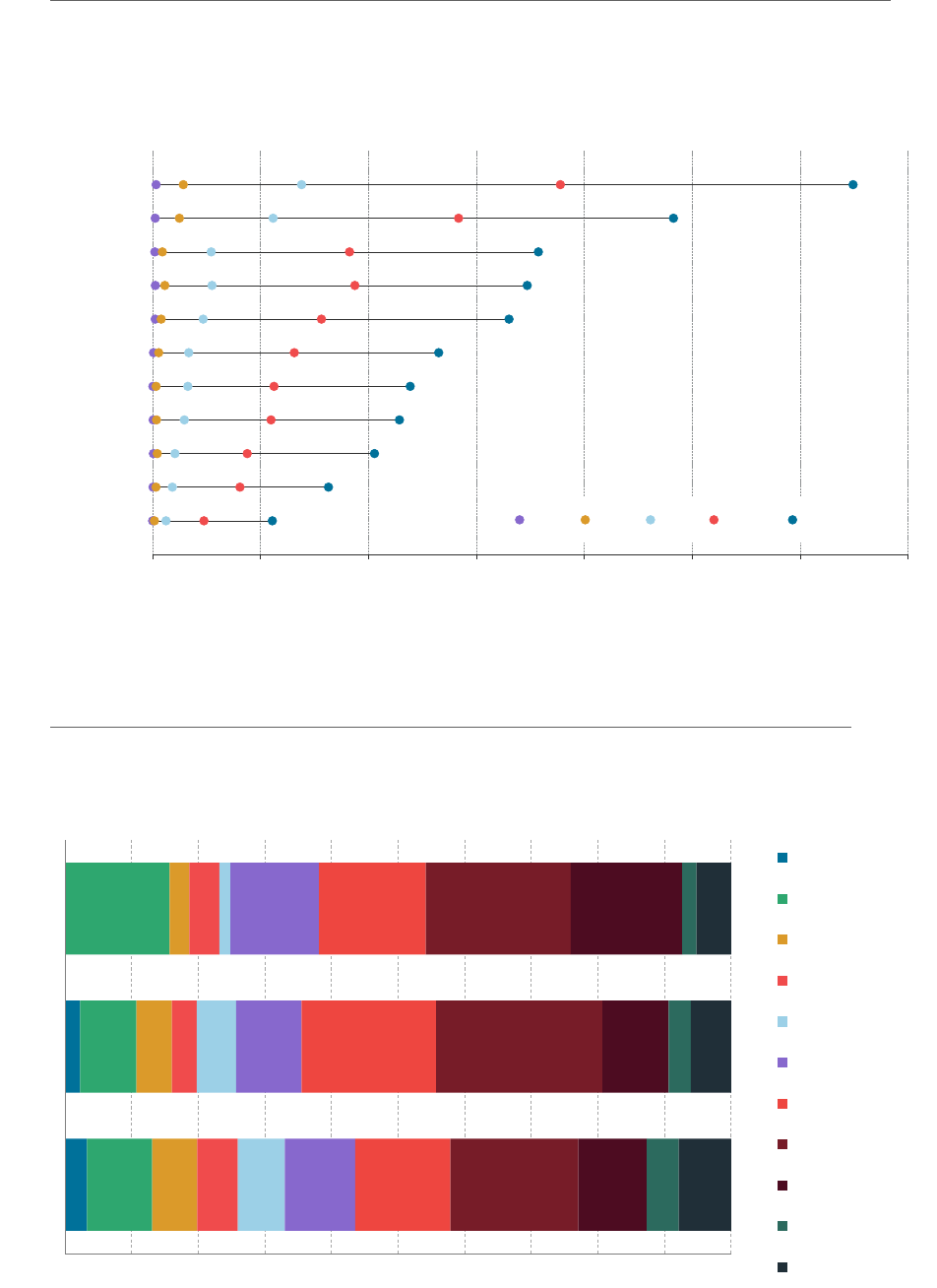

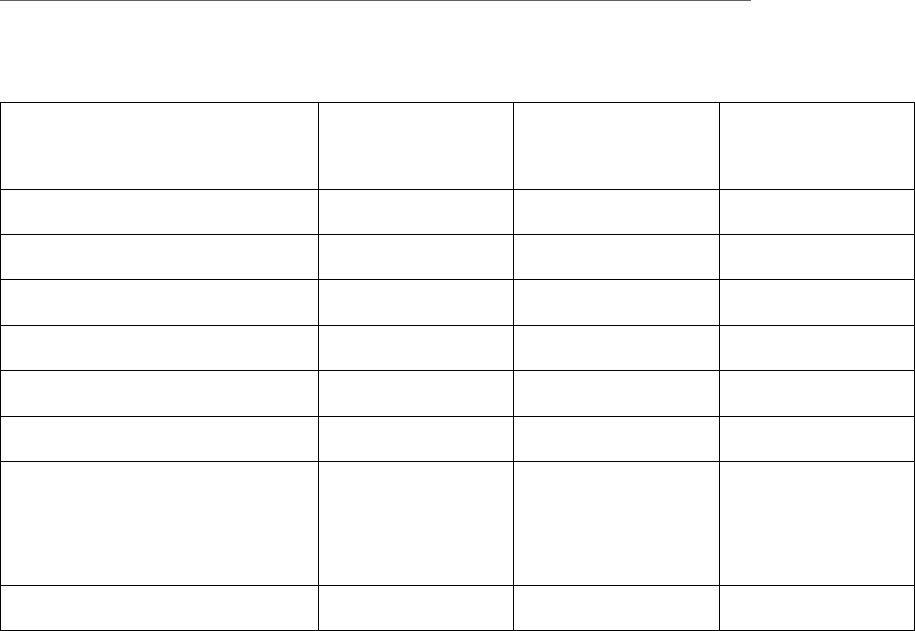

Volatility

A natural question is how stable the group of high wealth families is over time. In other

words, how frequently does a high wealth family become a lower wealth family or vice

versa. As Figure 13 shows, there is relatively little churn between families lower in the

wealth distribution just 7% of families in the bottom half of the wealth distribution move

into the top half over a two-year period. We look at this relatively short time period

because it best represents the possible regular change in the population of families

covered by a wealth tax that we might expect. Viewing the movement of families

across the wealth distribution over a longer time period results would result in higher

mobility, largely reflecting life-cycle effects (as highlighted by Figures 9a and b) and

intergenerational transfers (which are only partially covered by the WAS, making further

analysis beyond the scope of this paper) rather than movements due to volatility in

wealth holdings. However, there is more churn in wealth in the upper-middle of the

wealth distribution where a much higher proportion of those in the ninth decile move

up or down the wealth distribution, over the relatively short two-year period, than in the

lower half of the wealth distribution.

FIGURE 13: Movement along the wealth distribution is small over short periods

of time

Proportion of families moving between wealth groups over two years

NOTES: Observations for families who appear in both the 2014–2016 and 2016–2018 WAS samples are

linked between the two samples. Their position in the wealth distribution is recorded in both and the

share of households moving between groups is shown. The sample is weighted to account for differential

sample attrition based on a probit model including observed characteristics including family type, age and

education.

SOURCE: ONS, Wealth and Assets Survey.

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

25

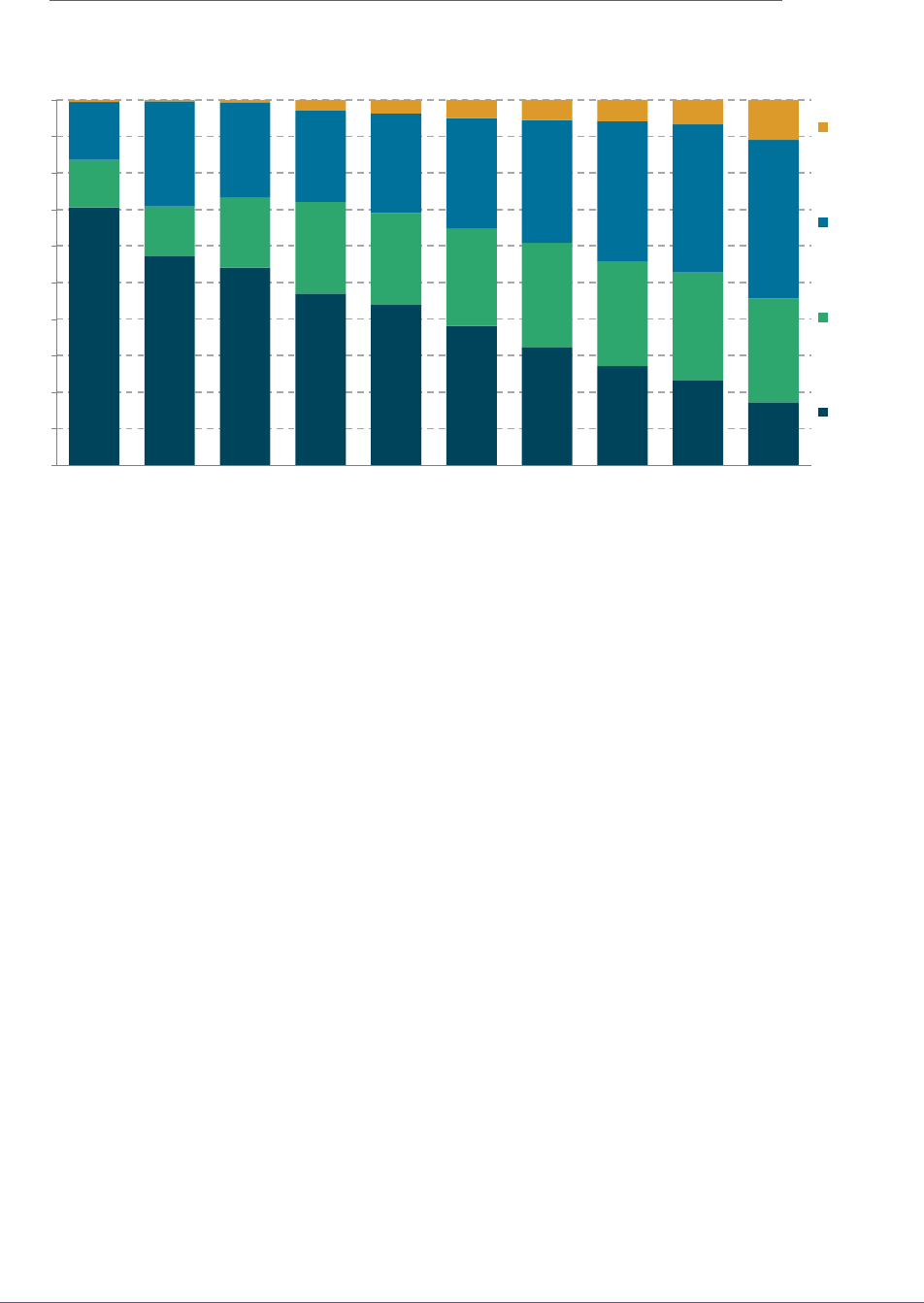

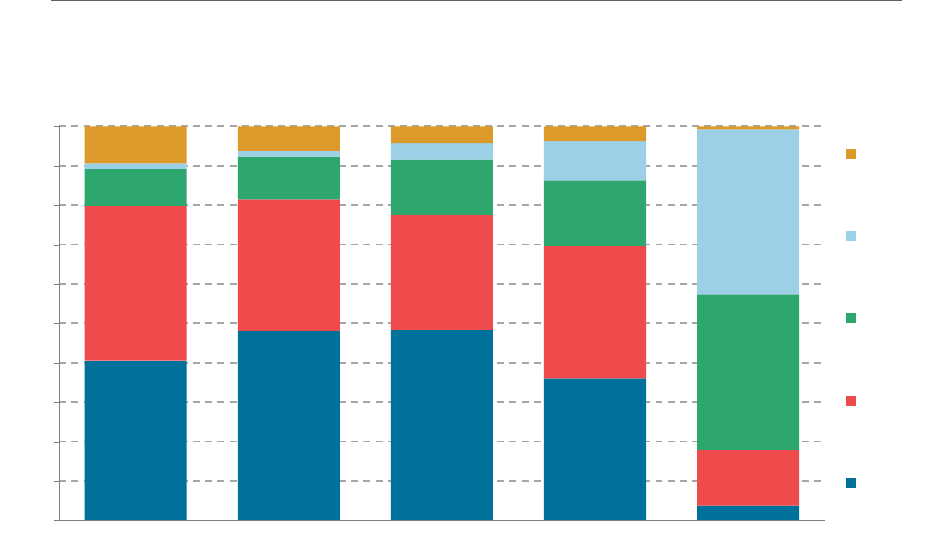

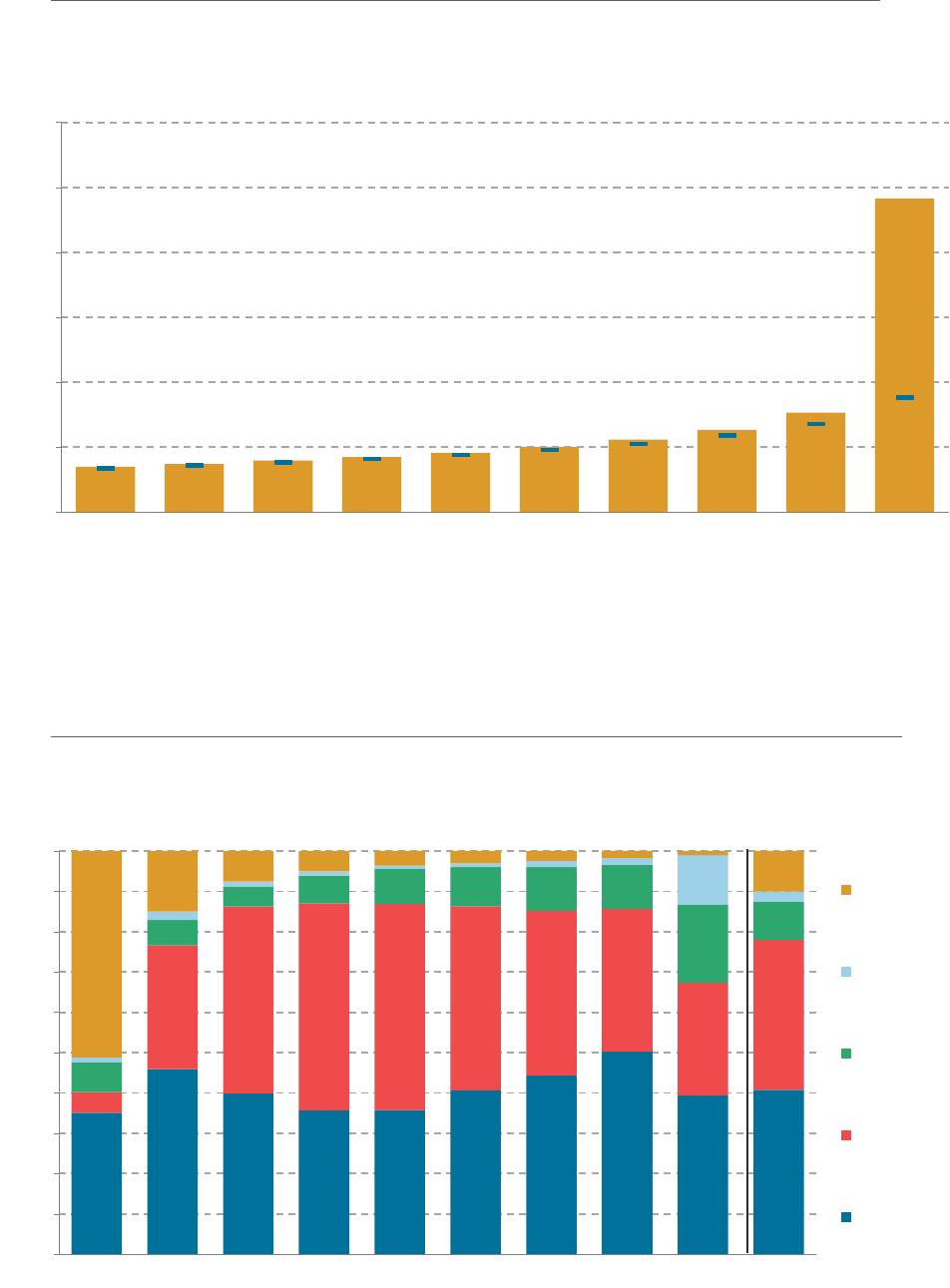

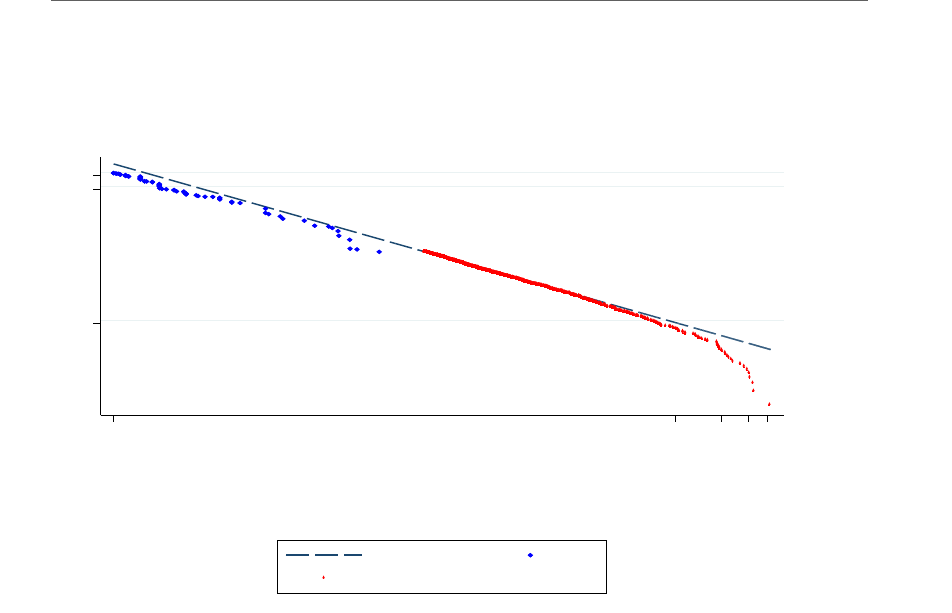

Asset composition

Unsurprisingly, there are big differences in the types of assets held by the average family

above each wealth threshold. Figure 14 shows the average share of total assets from each

broad asset class for families above each wealth threshold. There is a big step-change

between families above £2 million per-adult wealth and £5 million where the relative

importance of business and financial assets is much higher for the very wealthiest

families. This has important implications for policymakers considering implementing a

wealth tax; if the wealth tax threshold is set at a low level, the biggest sources of revenue

would be property wealth and pension wealth (excluding these asset-types would reduce

the tax base by 80%), in contrast, under a very high wealth tax threshold, financial and

business wealth would be the most important assets for the tax base.

FIGURE 14: The very wealthiest families hold much more financial and business

wealth than other wealthy families

Composition of net wealth by groups captured by each threshold: GB, 2016–2018

NOTES: Wealth is measured at the family level – single or couple adults and any dependent children within

a household. Total wealth includes net financial assets, net property assets, pension assets, business

assets and an adjusted measure of physical wealth (including cars, home contents, collectibles, etc). Figure

E5 shows this graph using an alternative measure of wealth which excludes main homes and pension

wealth.

SOURCE: ONS, Wealth and Assets Survey.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

£250k £500k £1m £2m £5m

Physical

Business

Financial

Property

Pension

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

26

Adjusting for data deficiencies

Adjusting for high wealth families

One of the major challenges with understanding the size and distribution of wealth,

particularly in any country without a wealth tax (and so comprehensive administrative

wealth data), is deficiencies in the data. Aggregate wealth measured in WAS using our

preferred definition is £14.4 trillion, but this is likely to be an under-estimate of true wealth

in the UK.

23

There are good reasons to think that wealthier households are less likely to

respond to surveys such as the WAS. For example, wealthier households will tend to have

more complicated set of assets and liabilities, making responding to the survey more

time consuming and difficult. The incentive payments offered to engage in the survey will

also be relatively less valuable to these households.

24

Item non-response where survey

respondents fail to include some of their assets is also a source of concern. The reasons

leading to lower high-wealth response rates will tend to magnify the higher up the wealth

distribution a family lies. This means there is a greater chance that the very wealthiest

people in the UK will not be captured by the sample leading to a significant gap in the

estimated total UK wealth and how much of wealth is held at the top of the wealth

distribution.

In order to explore the size of the potential under-coverage of high-wealth in the WAS,

we turn to the best available summary of the wealthiest families in the UK – the Sunday

Times Rich List (STRL). This is an annual publication which attempts to identify the 1,000

richest families that predominately live or work in the UK (we turn to the issues of primary

address, citizenship and tax residency location later). The data is compiled in such a way

so as to represent a plausible lower-bound estimate of each family’s wealth (Watts, 2020)

– and amounts to a total wealth value of £700billion. The STRL takes a cautious approach

to valuing wealth in a number of ways. First, not all assets are included – data is primarily

based on private and public business assets as well as known land holdings and other

items (such as art holdings). Private financial assets (excluding shares) will largely not

be captured as there is no available data in order to base their wealth estimates. Given

the composition of assets highlighted for the wealthiest observations in the WAS, this

suggests that there could be significant additional wealth not captured by the STRL.

There is also some risk that individuals who keep their wealth private, by holding wealth

via trusts for example, may be excluded from the list. Second, for private businesses with

high debts, the authors remove the owners from the STRL even if they may have high

enough wealth to be included. A third issue is that private businesses are valued at a

23 The official estimate of total wealth in the UK produced by the ONS is £14.6 trillion, but they use a different definition which

excludes business wealth and uses the full replacement cost for physical wealth (rather than our estimated current value based on

taking 25% of the replacement cost).

24 The ONS provide an ‘incentive’ payment of between £10 and £15 worth of vouchers for each survey.

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

27

relatively low multiple of earnings (10 to 12 times recent earnings compared to 20 times

for FTSE 250 companies).

Combining the two datasets we see that the WAS sample overlaps with the STRL; the

WAS includes observations for two households with wealth above £100 million.

25

This

suggests that the WAS is managing to sample some households at the very top of the

UK’s wealth distribution. In fact, when accounting for the weighting of households in the

WAS which overlap with the STRL, it appears that the WAS roughly captures the correct

number of households above the minimum threshold to be in the STRL.

Despite the coverage of high-wealth families in the WAS, it is likely that it is not

fully capturing total household wealth in the UK. This is because the very wealthy

observations in the WAS are not fully representative of the wealth of those captured by

the STRL. Indeed, the weighted total wealth of these two top households is just under

£300 billion, compared to £700billion in the STRL. This implies that at a minimum, the

WAS underestimates wealth at the top by £400billion. This is because the very wealthy

observations in the WAS are not fully representative of the wealth of those captured by

the STRL: given the wide range of wealth values in the STRL, the WAS observations that

do overlap with the top have wealth levels far below the top of the STRL. In addition, it is

likely the wealthiest families have large variations in the composition of their assets: the

WAS observations may not be a ‘typical’ top-wealth family.

Pareto distribution

Approach

The analysis presented so far is only indicative of the size of the potential missing

wealth; in order to fully estimate the value of missing wealth we implement a similar

approach taken by Vermeulen (2018) and Bach, Thiemann and Zucco (2019). The basic

idea underlying this approach is as follows. Suppose we know something about the

behaviour of the true wealth distribution at the top, but not its exact shape. The observed

distribution of wealth departs from the true distribution because of under-coverage of

wealth in the survey data. However, using information contained in the Sunday Times

Rich List, we can combine this with what we understand about the behaviour of the

wealth distribution to update our estimate of its exact shape.

Concretely, we assume that the top tail of the wealth distribution matches a Pareto

distribution, which means that the proportion of households with wealth above a certain

25

The most recent version of the publicly available version of the WAS microdata censors some observations to ensure that the data

does not disclose details about individual families.

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

28

threshold will be proportional to that threshold raised to a power.

26

This property defines

the ‘behaviour’ we expect the true wealth distribution to abide by. According to this

property, as you consider higher and higher wealth levels, the frequency of households

declines – and does so at a pace defined by the shape of the Pareto distribution. If

there is substantial under-coverage at the top in the survey data, then as we move up

the observed wealth distribution, the frequency of households will decline faster than

it should according to the Pareto distribution. However, we can use information on the

wealth of households in the Sunday Times Rich List to get a more accurate estimate of

the specific rate at which the frequency of households should decline, and hence the

shape of the overall distribution. There is a long history of empirical evidence which

suggests that wealth holdings follow a Pareto distribution (for example, Klass et al., 2006).

We estimate the specific shape of the Pareto distribution by pooling the data from the

WAS and the STRL, and estimate the distribution over this combined sample.

27

An important difficulty in taking this approach is that it assumes that the WAS sample

and STRL have a common underlying definition of wealth, and a consistent measure

of ‘units’ who hold the wealth. However, we know that is not the case. First, the asset

classes covered are different: the WAS data is a comprehensive account of all assets

and liabilities while the STRL is primarily based on business assets with some additional

assets added where available. Second, the STRL observations are taken at a broad family

level, and this often includes more than two adults and their dependent children (the

definition of family used previously). For example, in the 2020 list, the Barclay brothers

are listed jointly at 17th but were they to be part of the WAS survey, they would be treated

as separate households. In order to account for the first issue, we create a measure of

wealth in the WAS which most closely relates to the coverage of assets in the STRL –

specifically, we combine private business assets with domestic and foreign shares as well

as non-savings bonds, which are included in financial wealth in the WAS. This approach

will be imperfect because the publicly available information upon which the STRL is

based will not capture this exact definition of wealth for all observations; Appendix F

provides results based on alternative definitions of wealth as a robustness check. For

the second issue, we use WAS data at the household level (rather than at the family level

as with previous analysis), while there is relatively little empirical difference between the

data aggregated at a family and household level (particularly at the top of the distribution

26 Hence the Pareto distribution is also known as a power-law probability distribution. See Jones (2015) for a full explanation of the

mathematical form of the Pareto distribution and its relationship to the wealth distribution. Adapting his notation, the Pareto

distribution says that the fraction of wealth held by the top p percentiles is equal to 100pwhere the parameter sets the shape of

the distribution (or, in other words, the fatness of the tail); if =-0.5, the top percentile of the wealth distribution would have 10% of

total wealth while the top 2 percent of household would have just over 14% of total wealth.

27 For the estimation we follow the approach set out in Vermeulen (2018) for a finite sample with survey weights, as the WAS

observations have survey weights from the ONS and we assume that the STRL observations each represent an individual family.

Households are ranked by their wealth, from highest to lowest, so that for each observation we have a value for the proportion

of the sample which have wealth above a given threshold – in other words the dependent variable needed for estimating the

distribution parameter. We estimate the Pareto distribution using ordinary least squares (OLS) after adjusting the dependant

variable for sample weights and bias in log-log rank-size estimates, as suggested by Gabaix and Ibragimov (2012).

The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households |

Resolution Foundation

29

where households are less likely to include multiple adults outside of couples), the

maximal definition of the unit of analysis used by the STRL will be best approximated,

albeit imperfectly, with household data from the WAS.

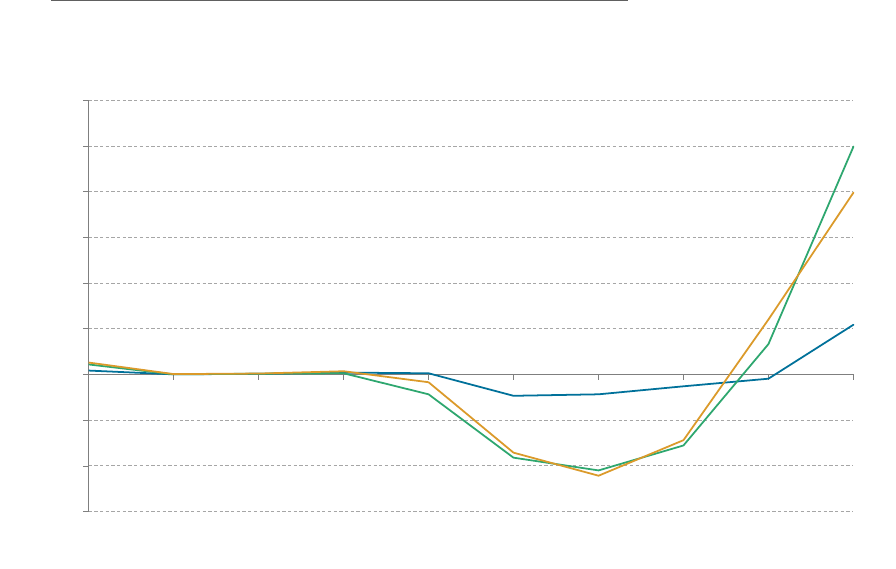

Estimated ‘missing’ wealth

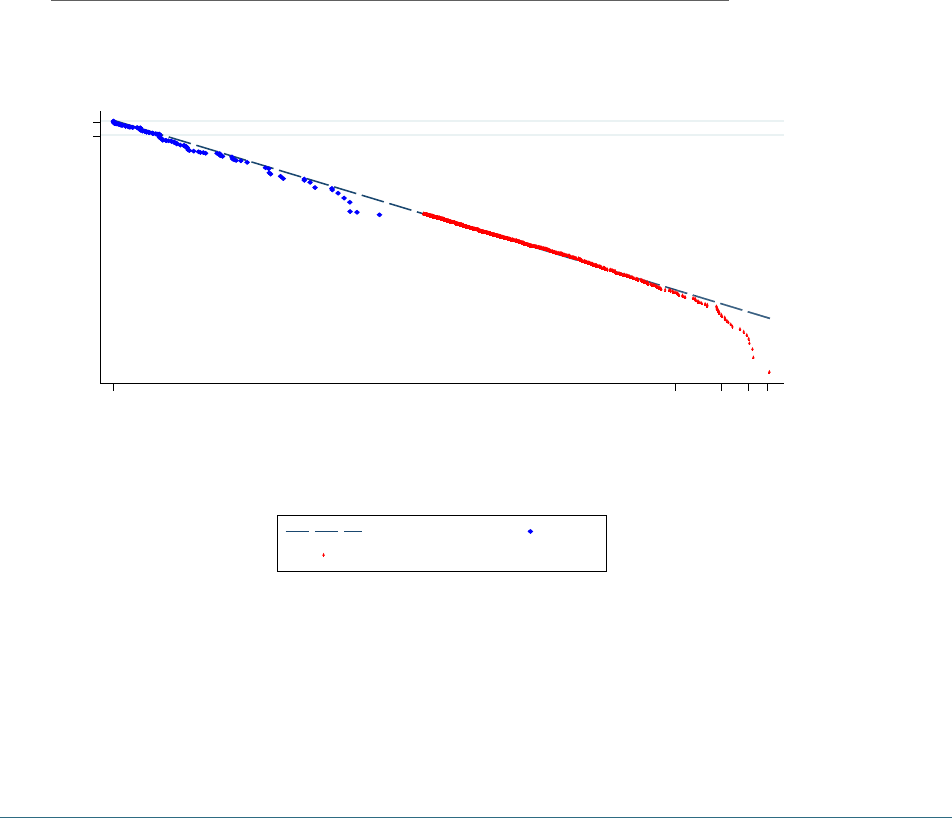

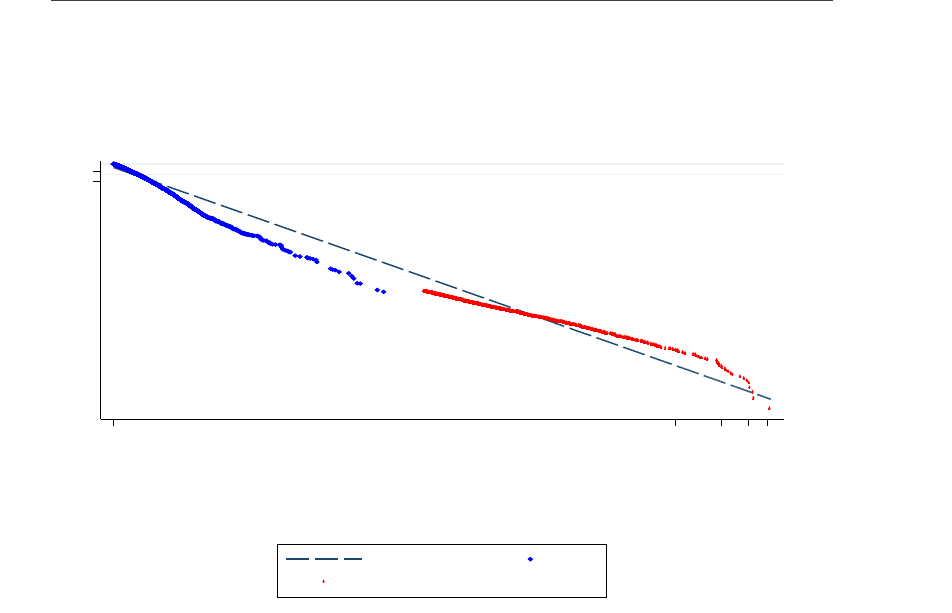

Figure 15 shows the fitted Pareto distribution using our definition of business wealth from

the WAS combined with the STRL, for observations with total business wealth above

£1 million.

28

The x-axis shows the level of wealth on a logarithmic scale and the y-axis

shows the weighted proportion of observations which have wealth higher than the level

indicated on the x-axis, also on a logarithmic scale. Inspection of the results suggest

that a Pareto distribution, which should look like a straight line in this space, provides a

reasonably close representation of top-tail wealth shares in the UK.

FIGURE 15: There is not a large gap between the WAS and STRL

Estimated Pareto distribution using WAS business assets and the STRL

Source ONS, Wealth and Assets Survey; Sunday Times Rich List.

When we calculate the predicted value of wealth which should be present across the

top-tail of the UK wealth distribution implied by the fitted Pareto distribution, it suggests

that the combined STRL and WAS observations modestly underestimate aggregate

28 Only observations with wealth above £1 million, which we take as the Pareto threshold, are included in this baseline specification.

In practise, the estimated Pareto distribution here is not particularly sensitive to the choice of threshold – Table F1 in the annex